Home » Posts tagged 'Central America'

Tag Archives: Central America

A Legacy of Violence: Impact Magazine 2018-19

In American politics, issues like immigration and the refugee crisis generate national headlines daily. But the complex dynamics of immigration are inextricably tied to U.S. history in the Americas, where a legacy of colonialism continues to define the relationship between the United States and the nations of Central and South America.

More than 50 years of interventions in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Panama, Chile, Brazil and other countries in the southern hemisphere have affected the lives of these countries’ residents in various ways. Many have resulted over the long term in the systematic destabilization of government coupled with a legacy of violence and military dictatorship, contributing to the reasons that immigrants may cite for wanting or needing to leave their homelands: gang violence, repression, dictatorship and more.

Several professors and students at John Jay have made it their life’s work to investigate the causes and ramifications of this instability, among them José Luis Morín, Claudia Calirman, Pamela Ruiz, and Marcia Esparza. We profiled these scholars in our latest issue of Impact magazine. Read on for a summary of our Impact feature story.

Suing for Justice

José Luis Morín, Chair of John Jay’s Latin American and Latinx Studies Department, is deeply involved with the process of finding justice for the victims of the American 1989 invasion of Panama. Morín had been in the thick of the invasion, which he recalls as “literally a war zone,” and subsequently filed a lawsuit on behalf of individuals who had been directly harmed, seeking reparations from the United States.

José Luis Morín, Chair of John Jay’s Latin American and Latinx Studies Department, is deeply involved with the process of finding justice for the victims of the American 1989 invasion of Panama. Morín had been in the thick of the invasion, which he recalls as “literally a war zone,” and subsequently filed a lawsuit on behalf of individuals who had been directly harmed, seeking reparations from the United States.

Nearly 30 years later, in December 2018, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights finally issued a decision in the case, holding the U.S. government solely responsible for the deaths of Panamanian citizens during the invasion; it is responsible for compensating the victims for damages.

Finally having a decision saying that the U.S. had violated human rights through its actions was a key step toward justice. Morín returned to Panama following the decision, going to communities to explain what this meant and speak to the individuals and families who were part of the case.

“What makes this particularly relevant, and so critical to the work we do in this department, is having our students learn about the history of Latin America and how the U.S. played such an integral role in how these countries developed,” said Morín.

Art Under Fire

The U.S. justified its intervention in Panama as a defense of democracy, but some U.S.-backed “democratic” leaders have turned out to be authoritarian dictators. This was the case in Brazil, where a right-wing authoritarian government ruled from 1964 to 1985.

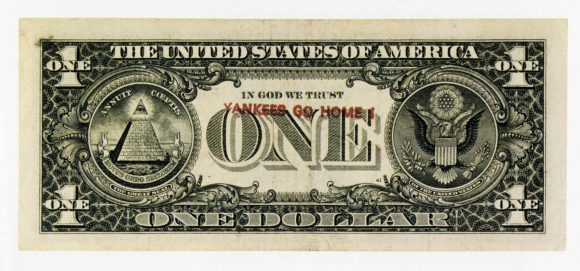

Claudia Calirman, Associate Professor of Art & Music, is an expert on artistic resistance to government repression in Brazil, and her research — including her first book, Brazilian Art Under Dictatorship — explores how art was expressed in mediums designed to thwart detection. These mediums include body art and what was called “ready mades,” which are every day objects modified to carry subversive or critical messages that could be circulated publicly without implicating the artist.

Claudia Calirman, Associate Professor of Art & Music, is an expert on artistic resistance to government repression in Brazil, and her research — including her first book, Brazilian Art Under Dictatorship — explores how art was expressed in mediums designed to thwart detection. These mediums include body art and what was called “ready mades,” which are every day objects modified to carry subversive or critical messages that could be circulated publicly without implicating the artist.

Calirman’s ongoing work explores different facets of Brazilian art over a variety of time periods, showcasing the ways Brazilian artists approach tough issues and combat repression. Her forthcoming book deals with Brazilian women’s struggles with the term “feminism” as it has applied to their work since the 1960s and ’70s. And Calirman is working on curating a Spring 2020 exhibit at John Jay’s Shiva Gallery about ongoing censorship of art in Brazil.

periods, showcasing the ways Brazilian artists approach tough issues and combat repression. Her forthcoming book deals with Brazilian women’s struggles with the term “feminism” as it has applied to their work since the 1960s and ’70s. And Calirman is working on curating a Spring 2020 exhibit at John Jay’s Shiva Gallery about ongoing censorship of art in Brazil.

Uncovering Violence

Pamela Ruiz is a recent graduate of the CUNY Criminal  Justice doctoral program whose dissertation analyzed the evolution of gang violence in the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. An explosion of gang violence in these Central American countries is connected to instability and the destabilization of democratic governments.

Justice doctoral program whose dissertation analyzed the evolution of gang violence in the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. An explosion of gang violence in these Central American countries is connected to instability and the destabilization of democratic governments.

Ruiz aimed to classify violence that is truly gang-associated, to dispel myths around violence and better target enforcement. “The perception is that all this violence is attributed to gangs,” she explained, ‘but when you go into a country and interview people, you discover that it’s different groups contributing to violence in different areas.”

Her quantitative methods are filling a key gap in research in the region, providing reliable data that policymakers can use to reduce violence, target corruption, and more.

Documenting Dictatorship

Marcia Esparza, Associate Professor of Sociology and an expert on genocide, state crimes, and human rights violations, would argue that, wherever violence and repression are to be found, remembering victims and commemorating resistance is vital in learning from the past and addressing present violence and corruption.

“If we don’t look at the long-term footprints of militarization on the local level, we cannot talk about democracy or democratic institutions,” she says. Esparza was inspired by her work interviewing genocide survivors in Guatemala to found the Historical Memory Project, which archives and draws on primary sources to memorialize the victims of genocide and state violence, and those who resisted it.

She also emphasizes the importance of helping John Jay students connect with their histories as part of a diaspora. Esparza’s students play a key role in the project’s efforts, as they organize and sort through the large archive to pull together educational exhibitions.

Shared History

The shared history of interventionist foreign policy and authoritarian rule has created a spider’s web of mutual entanglements that continue to tie the United States to its southern neighbors to this day. This long-term history of invasion and intervention by the United States has created patterns and threads that John Jay scholars trace in their efforts to understand, alleviate, and memorialize violence and instability in these countries, in order to achieve justice, create a lasting peace and, in the process, help some Latinx John Jay students better understand their own histories.

For the full feature, please visit the John Jay Faculty and Staff Research page to read the whole magazine in PDF form!

John Jay Featured Grant – Reducing Prison Overcrowding: Jeff Mellow + Deborah Koetzle

John Jay faculty and staff came together for a reception on May 14th to honor 76 of their own who received major and external grants and awards in 2018. The funded projects are a testament to the hard work John Jay’s community devotes to research and to honorees’ dedication to studies and creative work that strengthen the scholarly fabric of the institution. The awards funded projects of all types, from those with potential therapeutic implications to those that could change international policy, and more.

Among the honorees were Dr. Jeff Mellow and Dr. Deborah Koetzle. Their grant, from the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, took them to El Salvador to work on alleviating the severely overcrowded conditions in many Salvadoran prisons.

Both Dr. Mellow and Dr. Koetzle have been working to apply evidence-based, empirically-verified practices to corrections for many years, so when the opportunity came to apply their knowledge gained from research in the United States to an international setting, they knew they had to take it. The project took place in cooperation with El Salvador’s National Criminological Council and Director of the General Office of Penal Centers.

Prison overcrowding

El Salvador’s rate of incarceration is among the highest in the world — second only to the United States, with more than 600 out of every 100,000 persons incarcerated. Although the overcrowding rate is slowly coming down thanks to the construction of new prison facilities, the researchers described unhealthy conditions in some prisons. Some facilities were at 800 or 900 percent capacity, with bunks overfilled with bodies, increased risk of infectious disease, and insufficient room for programming or recreation.

Dr. Koetzle described the severely overcrowded prisons as “strangely quiet” and very still, as inmates have little room for movement. “No one should have to live in those types of conditions,” said Koetzle. “But the other side of that is really seeing the government and the system putting forward meaningful, genuine efforts to address it.”

Releasing the bottleneck

The counterpart to overcrowded higher security institutions are the granjas, or minimum security prisons, to which incarcerated individuals can transition as part of their rehabilitative journey toward release. Their gradual reintegration and movement through the system requires a protracted process of repeated assessments. “Inmates have to both finish a minimum of a third of their sentence, and also engage in very extensive programming to move from closed prisons to open prisons,” said Mellow. “But the problem is there’s a bottleneck, and only about 6% of the inmates, out of 40,000, are in the open prisons.”

As part of the government’s effort to ameliorate prison conditions and move people through the system more quickly, the researchers were engaged to hire, train and manage criminological teams — composed of one lawyer, one educator, one psychologist and one social worker — that helped to build capacity to assess inmate progress toward rehabilitation while drafting more than 2,000 proposals to improve the process based on empirical data collected throughout.

“Our goal was to improve the correctional system and policies, to maintain our relationships down there, and help [the government] to introduce additional evidence-based practice and risk assessments that we think can really help them open up bottlenecks and be more efficient and effective in identifying low-risk individuals to move them through the rehabilitative phases,” said Mellow.

“Our goal was to improve the correctional system and policies, to maintain our relationships down there, and help [the government] to introduce additional evidence-based practice and risk assessments that we think can really help them open up bottlenecks and be more efficient and effective in identifying low-risk individuals to move them through the rehabilitative phases,” said Mellow.

They brought to the process many collective years of experience in working to introduce standardized, evidence-based practice to the U.S. correctional system. Both professors also brought back lessons learned from their time in El Salvador that could translate to better practice in the United States, emphasizing the ways Salvadorans involved in the justice system are still encouraged to feel a part of their community on the outside. “They have families much more engaged, and they are really trying to provide for employment opportunities,” remarked Koetzle. “I think on those two fronts in particular, we could learn.”

Mellow also outlined elements of the rehabilitation program, broadly called “Yo Cambio,” that he felt were exceptional, including “conjugal visits, which we rarely do in the United States, and focus on vocational education. They also have a Fair Day where inmates will go out to sell all the wares they’ve made inside the prison, and the national Olympic game day. You can see that they are really trying to show that inmates are part of the community. They’re people.”

The life of a PI

Working on a large international grant was both a challenge and a source of immense satisfaction. “You’re wearing 100 different hats,” said Mellow, who was Primary Investigator on the grant. “Everything from drafting subcontracts to thinking about lunch for the trainings, to dealing with messages every day, getting everybody paid, and dealing with the funder. Plus doing the actual work, and writing the quarterly and final reports and analyzing the evaluation. If you think about it, you’re managing 40-something people.”

It was “not typical to have so many staff in institutions for this length of time,” added Koetzle, the project’s Senior Advisor. “[And] engaging in international work stretches you a little bit differently.” They took seven trips to El Salvador during the two-plus years of their grant work, and talked about the greater investment of resources, time and flexibility needed to pull off a successful overseas project.But the challenges created by managing a large grant from so far away were paired with a huge pay-off. Both Mellow and Koetzle agreed this was one of the most rewarding projects they’d ever undertaken, and talked about the valuable insights they had learned from working in a different context and system. They also had only positive things to say about their team of local staff, both about their capabilities and their constant enthusiasm and dedication.

“That’s something that really stood out — the number of times they thanked us for giving them the opportunity to help their country,” said Koetzle.

Next steps

Now that the grant has ended, as of February 2019, Dr. Mellow and Dr. Koetzle, along with co-PI and Senior International Officer in John Jay’s Office of International Studies and Programs Mayra Nieves and their program coordinator, PhD candidate and Salvadoran native Lidia Vásquez, are looking ahead. They are working on publishing their results with a Salvadoran university, in Spanish, and would like to see some of their recommendations translated to national policy. Their greatest hope, though, is to find continuing funding to keep doing the work to which they’ve dedicated so much time over the last two years, and perhaps even extend its scope to other nations in Central and South America with similar overcrowding and assessment challenges in their own criminal justice systems.

“We are hoping for the project to come back, “said Mellow. “That is our goal.”

Dr. Jeff Mellow is a Professor in John Jay College’s Criminal Justice Department, Director of the Criminal Justice MA Program, and a member of the doctoral faculty at the CUNY Grad Center. His research focuses on correctional policy and practice, program evaluation, reentry, and critical incident analysis in corrections.

Dr. Jeff Mellow is a Professor in John Jay College’s Criminal Justice Department, Director of the Criminal Justice MA Program, and a member of the doctoral faculty at the CUNY Grad Center. His research focuses on correctional policy and practice, program evaluation, reentry, and critical incident analysis in corrections.

Dr. Deborah Koetzle is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Management at John Jay College and the Executive Officer of the Doctoral Program in Criminal Justice. Her research interests center around effective interventions for offenders, problem-solving courts, risk/need assessment, and cross-cultural comparisons of prison-based treatments.

Dr. Deborah Koetzle is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Management at John Jay College and the Executive Officer of the Doctoral Program in Criminal Justice. Her research interests center around effective interventions for offenders, problem-solving courts, risk/need assessment, and cross-cultural comparisons of prison-based treatments.

Recent Comments