Home » Posts tagged 'criminal justice'

Tag Archives: criminal justice

New Faculty Spotlight Interview: Prof. Alessandra Early

Professor Alessandra Early is an assistant professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College and a dedicated criminologist whose academic journey is rooted in a passion for understanding the intricacies of human behavior and identity. From a childhood curiosity that questioned the fundamental nature of numbers to becoming a professor, her commitment to knowledge has been unwavering. With a background in psychology and sociology, she transitioned to criminology, driven by a fascination with the dynamics explored in shows like Criminal Minds.

Dr. Early’s research delves into the intersection of spatial dynamics, identity formation, and behavior, particularly focusing on queer experiences and the impact of social spaces. In this Q&A, Dr. Early shares her insights into research, professional achievements, mentoring philosophy, and her vision for contributing to the academic community.

Can you share a bit about your academic journey and what led you to pursue a career in criminology?

Since I was young, I’ve wanted to help people and investigate the “hows” and “whys” behind everything around me. As a kid learning math, I peppered my mother with questions incessantly, completely unsatisfied with the superficial and desperately seeking to learn a greater meaning. “Why is a one a one?” I asked. “What makes a two a two?” That pursuit of knowledge has become a core mission in my life and led me to become a professor today.

As an undergrad, I majored in psychology and sociology. I fantasized about becoming an FBI profiler thanks to my obsession with Criminal Minds, and I kept finding myself drawn to criminology courses. That tendency persisted when I pursued my master’s in sociology as well; I really connected with some professors who really believed in me and my work. I decided to follow that path and complete my PhD in criminology and criminal justice. (Though I moved away from law enforcement.)

Being a professor means I always have to adapt and evolve as new knowledge develops, which I love. I enjoy reading, learning, and problem-solving and my job asks me to engage in all three. Interacting with students is such a privilege because I want them to have the same light-bulb “Aha!” moments in my classrooms that I used to experience as a student myself.

Could you highlight some of your key research interests or projects, and how do you see them contributing to your field or broader society?

Broadly speaking, my research is rooted in three intersecting areas: Spatial and place-based dynamics, identity formation, and behavior. Specifically, I am interested in the ways in which spaces, particularly social spaces, impact how people understand themselves and can encourage or inhibit behavior. My dissertation, for example, explored how the historical, social, and cultural spatial dynamics of queer social spaces (such as bars and clubs), and using substances within them, can impact queer identities. One finding was that queer people strategically used substances to explore their identities and navigate queer vs. heterosexual social spaces.

Another project investigated the interplay between space(s), identities, and substance use through the experiences of primarily white heterosexual women who had experience with the rural methamphetamine market before being incarcerated. We emphasized the complex, violent, and empowering strategies that women used to confront and overcome gendered and sexualized expectations while participating within the patriarchal market.

My research interests engage in “queering” or destabilizing normative understandings of how we move through our environments, create meaning within them, formulate our identities in opposition to or with the help of those environments, and how those environments and the meanings we prescribe to them encourage or inhibit our behaviors.

Have there been any significant milestones or achievements in your professional journey that you are particularly proud of?

Currently, I’m most proud of my paper, The Role of Sex and Compulsory Heterosexuality Within the Rural Methamphetamine Market, which was published in Crime & Delinquency. Because of the precarious nature of grad school, sometimes it’s hard to see a project from inception to completion. To my and my co-author’s knowledge, this article represents the first paper to apply a queer criminological framework to examine the experiences of primarily cisgender and heterosexual white women. In 2022, the paper earned first place in the inaugural student paper award from the Division of Queer Criminology at the American Society of Criminology.

Do you have a mentoring philosophy, and how do you envision supporting students in their academic and professional development?

I approach teaching as a way to co-construct knowledge with students, with the goal of transforming the classroom into an encouraging space and making the material relatable and accessible. My mentoring philosophy builds upon that same foundation, emphasizing a collaborative and comfortable environment that I strive to offer all my mentees. I often describe my personal experiences with employing particular methodologies, concepts, or theories in order to demystify learning and the process of conducting research. In one-on-one student conversations and larger panel events, I speak candidly and transparently about the joys and challenges of being a Black queer woman in academia. While at conferences, I carve out time to bond with my mentees and ensure that I introduce them to fellow academics who share their interests to encourage networking and professional advancement. I let them know that my door is always open.

How do you envision contributing to the growth and development of our academic community in the coming years?

Although I have only spent a few months here at John Jay, I’m currently working to develop new courses that consider the ways in which queerness intersects with the carceral system and deepen our understanding of qualitative methodologies. I also look forward to carving out pathways that combine critical analyses and intersectional education.

Outside of academia, what are some of your hobbies or interests?

Outside of academia, you can find me practicing Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu karate and Matayoshi Kobudo (traditional weapons). Currently, I am a Shodan (1st-degree black belt) and I am preparing for my Nidan (2nd-degree black belt) test in the fall of 2024! I’ve also recently rekindled my love for video games (after a long hiatus during graduate school) and I’m back to gaming with my friends!

If you could give one piece of advice to students aspiring to excel in your field, what would it be?

Throughout my educational career, I have always carried my grandmother’s mantra and work ethic, which is the best advice I’ve ever received: Good, better, best. Never let it rest until the good is better and the better is the best. Though I’d make one small amendment — rest is important! Be sure to take breaks, but keep those intellectual fires burning.

Critical Sociology At Work Around the Globe – David Brotherton and the Social Change Project

Dr. David Brotherton is in high demand. As founder and director of the Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project, a research project at John Jay, he leads grants that span multiple countries and touch subjects from post-release reintegration to immigration and the deportation pipeline. His long background and expertise in critical criminology and sociology have suited him to lead the varied types of prestigious grants the project obtains. Brotherton says that the work has three key points of overlap: “One part is to be able to transcend the academy, to translate your findings from the theory to what it actually means to people. Second, you’re doing work that immediately has an impact, to understand or respond to a social problem. And the third thing is to work with the underrepresented, the marginalized, and to help develop knowledge that goes back to them, to empower them.”

With a mission statement like that, how could the Social Change Project not have ended up at John Jay College? Founded in 2017, the organization almost lived at the CUNY Graduate Center; however, a set of happy accidents brought it to John Jay, where, co-directed by Brotherton and Professor of Sociology Dr. Jayne Mooney, it has been funded every year. Under the project’s umbrella live two working groups: the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime, a working group that focuses on “crimmigration” and the dynamics of border control and migrant detention, and the Critical Social History Project, which features Mooney’s work chronicling the history of incarceration in New York. Today, the Social Change Project is doing work with ramifications that will be felt all over the globe.

The Deportation Pipeline

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

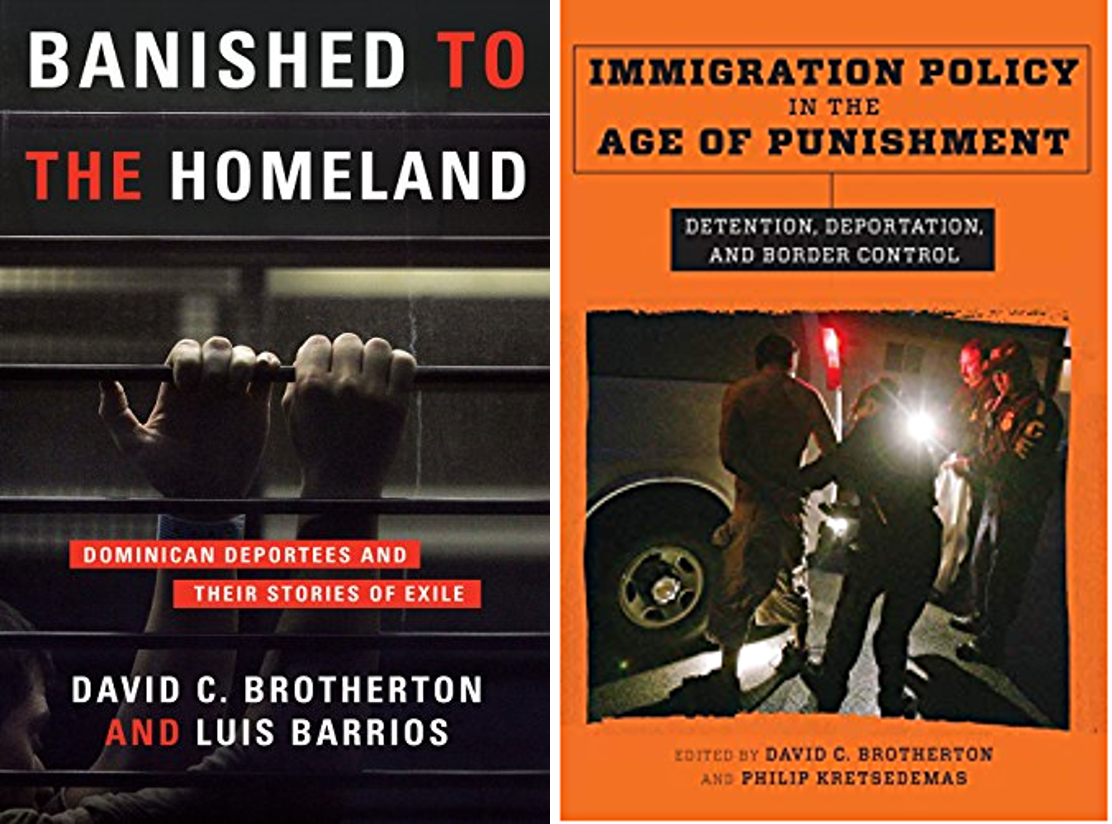

As he tells the story, Brotherton’s work with infamous gang organization the Latin Kings in New York brought him to the Dominican Republic in the early 2000s, where he was giving a talk on his project. “People didn’t want to know about the gangs, all they wanted to know was, why are you sending them all back here?” says Brotherton. “And I said, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll find out.’” That was the start of his investigations into transnational gangs and the issue of deportation, which at the time was not well-studied. That work has led to multiple grants and studies, books including Banished to the Homeland: Dominican Deportees and Their Stories of Exile and Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, Border Control, and the evolution of the multinational TRANSGANG project in Europe, which he advises.

This spring, Brotherton’s project will be working with personnel from Rutgers, including John Jay College graduate Sarah Tosh, to kick off the Deportation Pipeline Project, funded by the National Science Foundation. The team will interview a variety of subjects – immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, including some who have been detained for deportation hearings; lawyers; judges; and even ICE agents if possible – to understand the racialized “deportation pipeline” that runs through NYC back to the Caribbean, and the current situation these communities are living through under the Biden Administration.

“We need to understand all this, and then we’re going to be looking at all the texts that come down, the sanctions, all the laws. We know that Biden has said we’re going after criminal agents and gang members, which is just carrying on from Trump, but I thought we were supposed to have a new, more humane approach. So is it new wine in old bottles or are we going to get a real change in behavior? I don’t know.”

The two-year study will culminate in a book on the topic, as well as a conference with representatives from other municipalities. But Brotherton is already looking past the conclusion of the research to a potential comparative study in another large city or small town, to understand the dynamics of deportation in other American environments with similar demographics being targeted by immigration officials.

Critical Gang Studies

The Social Change Project is also looking forward to wrapping up several projects in the coming months. Since 2019, Brotherton has been consulting for the World Bank in El Salvador, developing national strategies for rehabilitation and reinsertion programs for formerly-incarcerated gang members in that country, which has the second-highest rate of imprisonment in the world after the United States. In April the project published a paper summarizing those findings, and expanding on them. “As we were writing this, we realized there is no real program for rehabilitation anywhere in Latin America, no probation, nothing like that,” says Brotherton. “Once you come out of prison, you’re on your own. So what we’re developing for El Salvador is really a model for the whole of Latin America.”

And July will see the publication of an edited volume, the Routledge International Handbook of Critical Gang Studies, which Brotherton edited along with Rafael Jose Gude, a Research Fellow at the Social Change Project. The book, which includes chapters by a number of CUNY faculty and graduates, will offer new perspectives on gang studies, placing them in the context of their political and social environments. According to Brotherton, it will cover perhaps 18 different countries and will be the largest handbook Routledge has ever released at nearly 900 pages long.

Incarceration and the Credible Messengers

Finally, Brotherton is working on a book on the Credible Messenger phenomenon, due out in 2022. The book, titled What’s Love Got To Do With It?: Credible Messengers and the Power of Transformative Mentoring, begins with a history of the now-widespread program, which recruits the formerly-incarcerated to intervene with young, at-risk kids from their neighborhoods, to keep them away from involvement with the criminal legal system. The book also incorporates qualitative research, including interviews with Messengers, kids, and administrators, as well as the currently incarcerated.

The Social Change Project and Brotherton himself are juggling many projects, each with many moving parts. But Brotherton relies on the connections he’s made over his career teaching at both John Jay and the CUNY Graduate Center, and doing research around the world, to keep the plates spinning. “It’s difficult,” he says. “Sometimes it gets overwhelming, but I always try to make sure I’ve got really good people in each project.”

At the end of the day, Brotherton is proud to be doing work that makes a difference for underserved, understudied communities that can face immense challenges. “I think the project carries on a rich tradition at John Jay. We’re following that tradition of socially conscious, critical social science.”

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Frank Pezzella Wants Increased Accountability on Hate Crime Reporting

During the chaotic years of the Trump Administration, the United States experienced a rise in hate crimes. This increase has been confirmed by FBI data collection, media reporting, and independent scholarship. According to Dr. Frank Pezzella, an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College and a scholar of hate crimes, four out of the past five years, from 2015 to 2019, have seen consecutive increases in hate crime offending in this country, something he says is new. Nine of the ten largest American cities had the most dramatic increases in hate crimes – including New York City.

Hate crimes, or bias crimes, are strictly defined by the FBI. The organization sets out 14 indicators that must be present for a criminal offense to be classified as a hate or bias crime, that provide objective evidence that the crime was motivated by bias. But according to Dr. Pezzella, the evidence to meet those criteria isn’t always clear. Not every hate crime is as flagrant as the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016 or the 2018 attack on Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue. To establish a hate crime was committed, first responding police officers must look for evidence of bias motivation – what Pezzella calls an “elevated mens rea” requirement. But bias can only be committed against legally protected categories, like race and ethnicity, sexual or gender orientation, disability, or religion, which vary from state to state. And the additional paperwork and procedural requirements that come with classifying an incident as a hate crime are, in his words, disincentivizing police reporting.

Undercounting Hate Crimes

The result of these complications is rampant underreporting. In his new book, The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America, Dr. Pezzella looks at the reasons why hate crimes are so undercounted in the United States, and proposes some solutions for what law enforcement and policymakers can do to correct the issue. Since the enactment of the federal Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990, which required the Attorney General to collect data about hate crimes, the FBI has been fulfilling this mandate in the form of the Hate Crime Statistics Program, published annually as part of the Uniform Crime Report. According to Dr. Pezzella, since 1990 the UCR has reported an average of roughly 8,000 hate crimes per year; but victims, he says, report around 250,000 hate crimes per year. He attributes this substantial gap to a variety of factors including the evidentiary and procedural barriers noted above. In addition, only about 100,000 of these victimizations are ever reported to the police in the first place. And when victims do report, police departments are under no legal requirement to pass their findings on to the FBI.

The result of these complications is rampant underreporting. In his new book, The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America, Dr. Pezzella looks at the reasons why hate crimes are so undercounted in the United States, and proposes some solutions for what law enforcement and policymakers can do to correct the issue. Since the enactment of the federal Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990, which required the Attorney General to collect data about hate crimes, the FBI has been fulfilling this mandate in the form of the Hate Crime Statistics Program, published annually as part of the Uniform Crime Report. According to Dr. Pezzella, since 1990 the UCR has reported an average of roughly 8,000 hate crimes per year; but victims, he says, report around 250,000 hate crimes per year. He attributes this substantial gap to a variety of factors including the evidentiary and procedural barriers noted above. In addition, only about 100,000 of these victimizations are ever reported to the police in the first place. And when victims do report, police departments are under no legal requirement to pass their findings on to the FBI.

“Of the roughly 18,500 police departments, only maybe 75% participate in the Uniform Crime Report hate crime reporting program – note that it is voluntary,” says Pezzella. “So we don’t even know about hate crimes in 25% of precincts. And of the participating 75%, roughly 90% report zero hate crimes every year. So one of the reasons we wrote the book is that, either we don’t have hate crimes the way we think we do, or we have a systemic reporting problem.” It’s obvious which he believes is true.

The consequences of underreporting hate crimes are severe, Dr. Pezzella says. “To the extent that we underreport both the type and extent of victimization, it really does put a specific policy issue in front of us. We need to know who’s being affected, how they’re being affected, and the extent of the effect, in order to fashion remedies.” The only way to target treatment and services for the most vulnerable and likely victims is through accurate reporting.

Remedying Undercounting

In order to remedy undercounting and better target policy, Dr. Pezzella presents a number of recommendations in The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America. He calls for changes to take place within police departments, at the level of state and local politics, and in the criminal legal system. First, he suggests that every precinct have a written and clearly posted hate crime policy, and that every officer be trained to understand the rules for identifying bias crimes and the statutes governing them in their particular state. He would also like to see greater police-community engagement on this issue, with better tracking of non-criminal bias incidents – like seeing a swastika or other racist tag in the neighborhood – which Pezzella says often lead to violent bias crimes. He would especially like to see hate crime reporting made mandatory, with penalties or audits following a departmental report of zero bias crimes in a year.

Stepping out of police departments, Dr. Pezzella also calls for greater engagement from state and local politicians, who after all control the purse strings as well as set state legislation, but who are often hesitant to call attention to a problem with hate crimes in their district. Finally, he wants prosecutors’ offices to commit to seeking hate crime convictions, rather than settling for the easier task of convicting an offender for non-bias equivalents. With every actor across the board invested in tackling hate crimes and being transparent and proactive about applying best practices, offenders are put on notice that the community, including police, won’t allow these harmful crimes to continue.

Vicarious Victimization

Dr. Pezzella has been studying hate crimes since his graduate school years at SUNY-Albany, but he doesn’t feel he’s reached the end of this line of research. Going forward, he is interested in studying the deleterious and vicarious effects hate crimes can have on the victims’ communities. Because bias-motivated offenders target victims based on what they are rather than what they do, Dr. Pezzella says, there is a sense that anyone could become the next victim. This impersonal threat undermines societal ideals of trust and equality, and can even affect property values, as whole groups feel unsafe in certain areas and may be forced to relocate. Pezzella also mentions the psychological and emotional impacts of feeling under threat for simply being who and what you are. “When a victim goes home and says they were a victim of a hate crime, in what way does it impact the quality of life or sense of safety for secondary victims [i.e., the victim’s community]?” he asks. “What do they do? While we understand the direct impact, we know less about this vicarious impact, and how far it extends beyond the primary victim.”

He also has his eye on current events, especially the rise of domestic terrorism in the United States. Dr. Pezzella is concerned about the growing number of organized hate groups in recent years, and how emboldened they have been by rhetoric from the top levels of government. While many mass shootings have been categorized as domestic terrorism, Pezzella also sees evidence of bias that might categorize these events as hate crimes. If they are being left out of crucial counts that help to allocate resources and fight back against hate in this country, he wants to know.

Dr. Frank Pezzella is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College. His primary research focus is on the causes, correlates, and consequences of hate crimes victimizations. He also conducts research on issues that relate to race, crime and justice. In addition to his most recent book, he is also the author of Hate Crime Statutes: A Public Policy and Law Enforcement Dilemma, as well as numerous peer-reviewed articles.

Dr. Frank Pezzella is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College. His primary research focus is on the causes, correlates, and consequences of hate crimes victimizations. He also conducts research on issues that relate to race, crime and justice. In addition to his most recent book, he is also the author of Hate Crime Statutes: A Public Policy and Law Enforcement Dilemma, as well as numerous peer-reviewed articles.

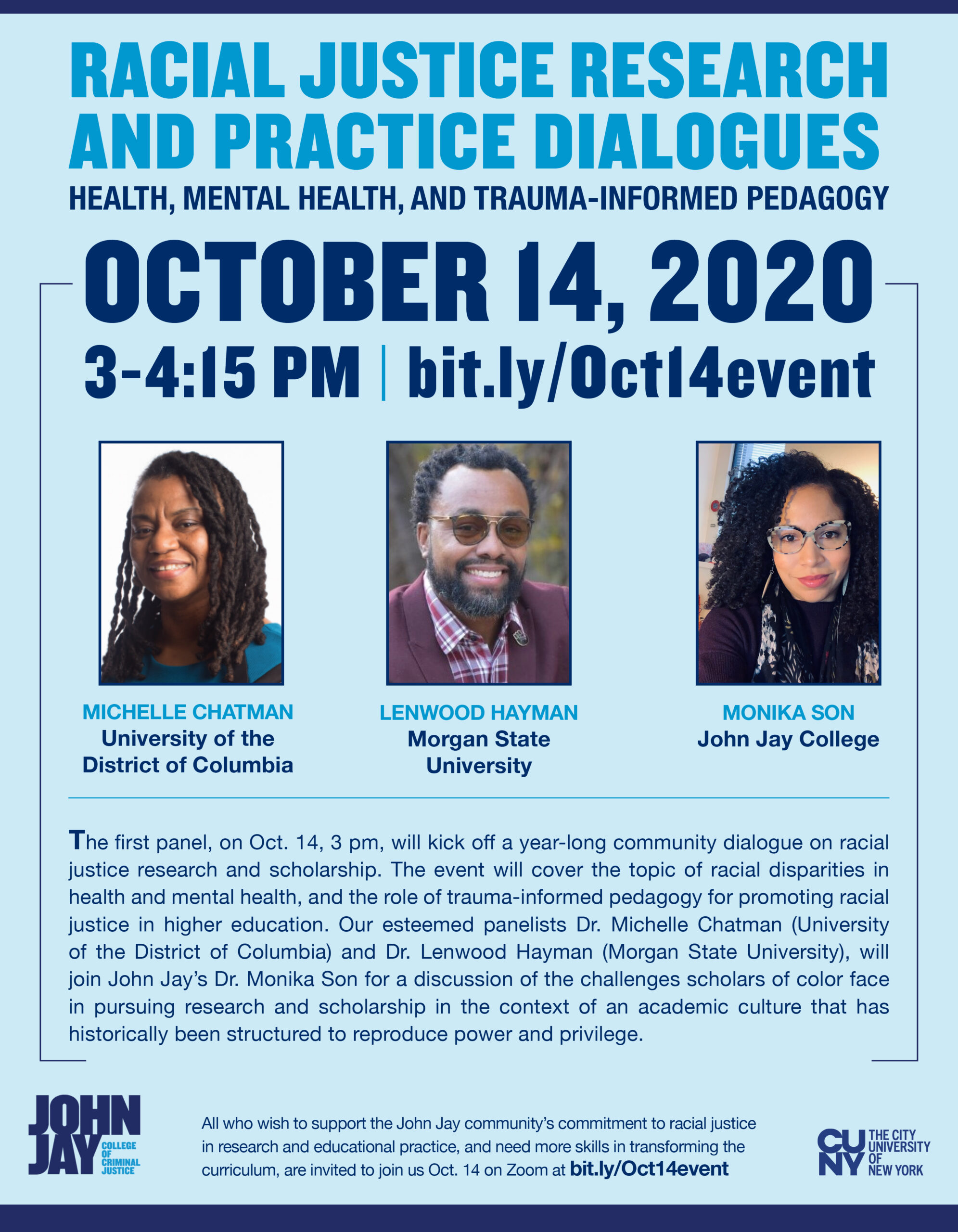

Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues 2020-23

The Office for Academic Affairs through its Office for the Advancement of Research, in collaboration with Undergraduate Studies and a faculty leadership committee representing Africana Studies (Jessica Gordon-Nembhard), Latinx Studies (José Luis Morín), and SEEK (Monika Son), sponsored a year-long community dialogue on racial justice research and scholarship across the disciplines. John Jay College faculty, students, and the broader community were invited to join four panel discussions and four hands-on workshops that invited a more in-depth discussion about changing the ways we teach and learn – specifically, by facilitating meaningful engagement with scholarship by and about people of color, and promoting the incorporation of research on structural inequities into curriculum college-wide. Over the course of the 2020-2021 academic year, events covered multi-dimensional topics including:

- racial disparities in health and mental health and trauma-informed pedagogy;

- the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative;

- economic inequality; and

- racism and discrimination in the criminal legal system.

Each panel was facilitated by a John Jay faculty member who also led a follow-up workshop intended to engage participants more deeply in the subject matter and promote best practices for cultivating racial justice in our classrooms and around the college. Each panel was recorded, and the recordings can be found below, as well as resource guides for further self-guided learning and curricular reform.

Series events, recordings and resources

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Panelists: Dr. Michelle Chatman (UDC) & Dr. Lenwood Hayman (Morgan State University)

Facilitator: Dr. Monika Son (JJC)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/NYTxARHOALw

Resources:

- Ayers, W., Ladson-Billings, G., & Michie, G. (2008). City kids, city schools: More reports from the front row. The New Press. Introduction, pgs 3-7.

- Chatman, MC. (2019). Advancing Black Youth Justice and Healing through Contemplative Practices and African Spiritual Wisdom. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 6(1):27-46.

- Monzó, L. D., & SooHoo, S. (2014). Translating the academy: Learning the racialized languages of academia. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(3), 147–165. DOI: 10.1037/a0037400

- Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Arch of Self, LLC, https://www.yolandasealeyruiz.com/archaeology-of-self

For additional suggested readings, prompts for discussion, and curricular resources, download our full event guide: RJD Event 1.1 Homework and Readings.

Event #2: Race and Historical Narrative — Correcting the Erasure of People of Color

The second panel in the OAR/UGS Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues series, on November 11 at 3 pm, will shine a light on the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative commonly taught in the United States. This erasure is harmful to students of color in particular, as they do not see themselves represented in the stories told about this country, and actively harms people of all races by failing to present an accurate picture of the country’s founding and history.

Panelists: Dr. Paul Ortiz (UFL) & Dr. Suzanne Oboler (John Jay College)

Facilitator: Dr. Edward Paulino (John Jay College)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/WRIDHIA_a94

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the RJD Event 2.1 – Readings.

Event #3: Economic Inequality and Wealth Disparities

Panel Discussion – March 24, 2021, 4:30 – 5:45 pm

Panelists: Dr. Naomi Zewde (CUNY SPH) & Dr. Stephan Lefebvre (Bucknell University)

Facilitator: Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard (JJC)

Event Recording: https://youtu.be/_lp93i3EHqE

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Economic Inequalities – Resources.

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Panel Discussion – April 21, 2021, 3 – 4:15 pm

Panelists: Dr. Jasmine Syedullah (Vassar College) & Professor César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández (University of Denver, Sturm College of Law)

Facilitator: Professor José Luis Morín (JJC)

Recording: https://youtu.be/OZ8N-c7Gob0

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Resources – Racism in the Criminal Legal System

The series continued in academic year 2021-2022, expanding the scope of the discussions with panels on racial equity in disaster recovery.

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

The fifth panel took place on November 1, 2021, and addressed the interdependent roles of government agencies, community-based and non-governmental organizations in promoting or hindering equitable outcomes in post-disaster situations. Panelists included Kim Burgo (Catholic Charities), Craig Fugate (One Concern), Dr. Jason Rivera (Buffalo State College), Dr. Warren Eller (John Jay College), and Dr. Dara Byrne (John Jay College). Find the recording at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQkjxw6RcKg.

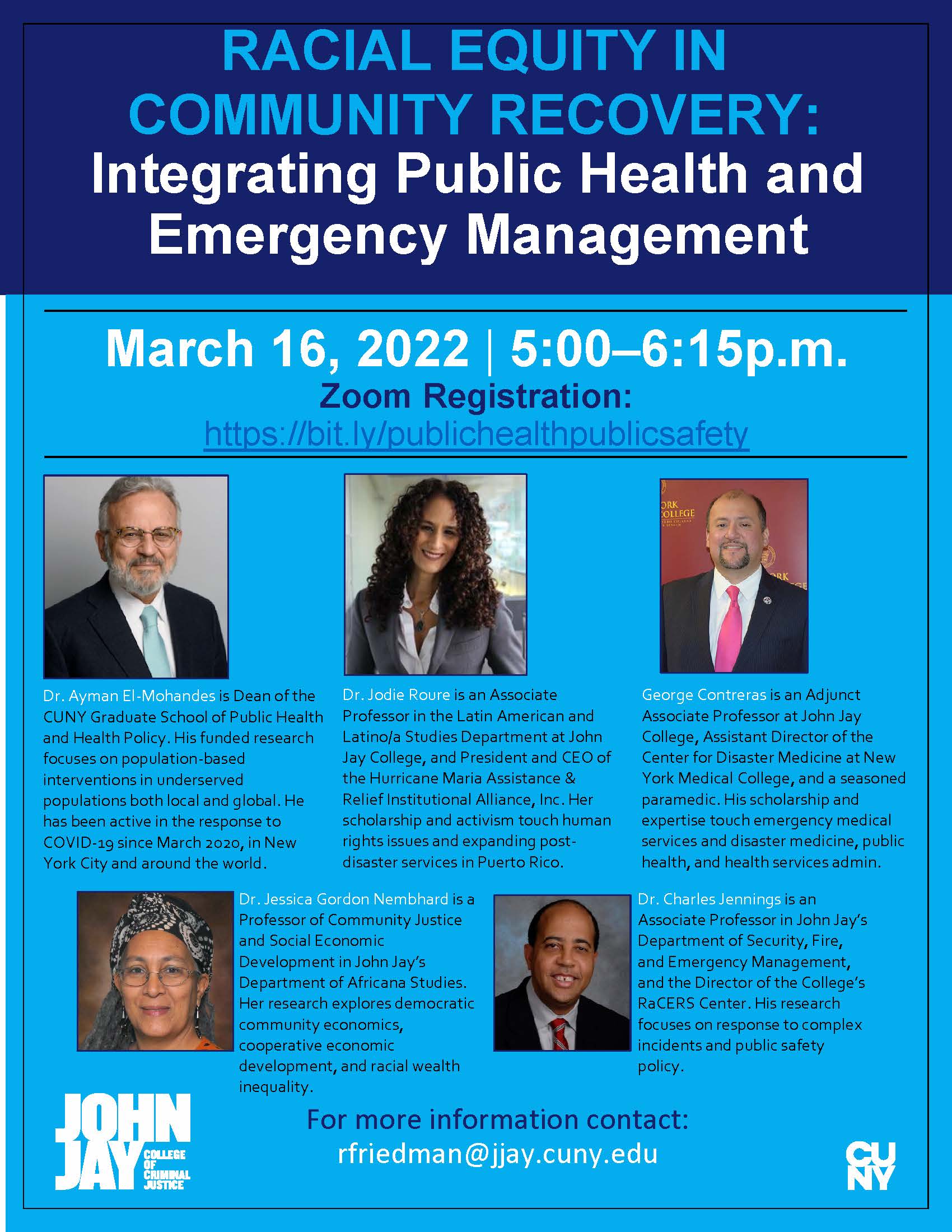

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

The sixth panel in the series, which took place on March 16, 2022, continued the theme of racial equity in disaster recovery. Panelists explored the overlapping roles of the institutions of public health and public safety in promoting equitable outcomes in post-disaster recovery, addressing the intersectional challenges faced by people of color and other marginalized communities. The conversation took special note of the particular context of post-COVID recovery. The participants were Dr. Ayman El-Mohandes (CUNY Graduate School of Public Health), Dr. Jodie Roure (John Jay College), and George Contreras (New York Medical College, John Jay College). The moderators were Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard and Dr. Charles Jennings (John Jay College). A full recording of the event is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4u9wUyjr5Sg&list=PL-B85PTQbdJj5UJhqiddjs1_9p90pZXTZ&index=6.

Resources:

- , 2020: COVID-19: A Barometer for Social Justice in New York City, American Journal of Public Health

- El-Mohandes, A., White, T.M., Wyka, K. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adults in four major US metropolitan areas and nationwide. Sci Rep

- Roure, Jodie G. The Reemergence of Barriers During Crises and Natural Disasters: Gender-Based Violence Spikes Among Women and LGBTQ+ Persons During Confinement. Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, pp 23-50, 2020.

- Jodie G. Roure, 2020 presentation: Children of Puerto Rico & COVID-19: At the Crossroads of Poverty & Disaster.

- Jodie G. Roure, Immigrant Women, Domestic Violence, and Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico: Compounding the Violence for the Most Vulnerable. The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 2019.

- Contreras GW, Burcescu B, Dang T, et al. Drawing parallels among past public health crises and COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.202.

Using Crime Science to Fight for Wildlife

There is no question that the fashion industry causes great harm to the environment. The industry’s faddish nature, combined with the overproduction of low-cost, low-quality pieces, is designed to encourage overconsumption. Production of fast fashion garments eats up precious resources, like clean water and old-growth forests, and discarded clothing can sit in landfills for hundreds of years, thanks to synthetic materials used in construction.

According to scholars Monique Sosnowski—a Ph.D. candidate in criminal justice at the CUNY Graduate Center—and John Jay Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice Dr. Gohar Petrossian, pollution is not the fashion industry’s only crime. In a new article, they investigated what species were being utilized for the fashion industry, which is worth over $100 billion globally, in order to better understand the damage the industry causes to wildlife and wild places.

Sosnowski and Petrossian looked at items imported by the luxury fashion industry and seized at U.S. borders by regulatory agencies between 2003 and 2013. Their study found that, during that decade, more than 5,600 items incorporating elements illegally derived from protected animal species were seized. The most common wildlife product was reptile skin—from monitor lizards, pythons, and alligators, for the most part—and 58% of confiscated items came from wild-caught species. The authors also found that around 75% of seizures were of products coming from just six countries: Italy, France, Switzerland, Singapore, China and Hong Kong. The heavy involvement of the European countries was unexpected, according to Dr. Petrossian, because they are key players in fashion design and production but “don’t generally come up in broader discussions on wildlife trafficking.”

THE SCIENCE OF WILDLIFE CRIME

The paper applied “crime science, a body of criminological theories that focus on the crime event rather than ‘criminal dispositions,’ to understand and explain crime. The overarching assumption is that crime is an opportunity, and it is highly concentrated in time, as well as across place, among offenders, and victims,” says Dr. Petrossian. Their scientific approach enabled the authors to analyze patterns and concentrations in wildlife crime, which Sosnowski notes is among the four most profitable illegal trades.

“We are currently living in an era that has been coined the ‘sixth mass extinction,’” she says. “It is crucial that we understand the impact that humans are having on wildlife, from habitat loss to the removal of species from global environments. Fashion is one of the major industries consuming wildlife products.”

A background in wildlife conservation, including unique experiences like responding to poaching incidents in Botswana and rehabilitating trafficked cheetahs in Namibia, led Monique Sosnowski to a Ph.D. in criminology; she wanted to move beyond a more traditional conservation-informed approach to address what she’d seen in the field. Working with Dr. Petrossian on a series of studies applying crime science to wildlife crimes has given her a broader view of the effects of wildlife-related crime on global ecosystems.

CREATING SOLUTIONS, SAVING WILDLIFE

Why is it important to understand what species are most commonly used in luxury fashion products, and where they are coming from? A study like this one provides information about trends that policymakers can use to strengthen or focus enforcement and inform better understanding of the issues. Sosnowski calls this “the key to devising more effective prevention policies.”

Currently, global regulation of the trade in wildlife products, including leather, fur, and reptile skin that come from species both protected and not, is the province of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES); this treaty aims to ensure that international trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. But the treaty is limited in scope.

“Given the prevalence of exotic leather and fur in fashion, we believe CITES and other regulatory bodies should enact policies on its use and sustainability in order to protect wild populations, the welfare of farmed and bred populations, and the sustainability of the fashion industry,” Sosnowski says.

Consumers also have a role to play. “We are all led to believe that products found on the shelves are legal, but as this study has demonstrated, that isn’t always the case. Consumers of these products are the ones who have the power to change the behaviors of a $100 billion industry. We need to ask questions about where our products were sourced, and respond accordingly.”

###

Summarized from EcoHealth, Luxury Fashion Wildlife Contraband in the USA, by Monique C. Sosnowski (John Jay College, City University of New York) and Gohar A. Petrossian (John Jay College, City University of New York). Copyright 2020 EcoHealth Alliance.

Bringing Justice Back to the System: Impact Magazine 2018-19

Although it may seem obvious, the basic question of fairness is of huge concern to those interested in reforming our nation’s criminal justice system. This is especially important in the courtroom. “The administration of justice,” says John Jay constitutional law professor Gloria Browne-Marshall, “is supposed to be done as equally under the law as possible.” That’s the concept of due process.

But the system doesn’t always work fairly. “Mass incarceration … is unfortunately disproportionately shouldered by people of color,” said Browne-Marshall. So how do we change things to ensure equitable outcomes?

Behind the scenes, a host of scholars at John Jay College are leading the charge to develop findings, share knowledge, and train officers of the court to promote courtroom practices that are more impartial and lead to real justice. Read on to be introduced to these scholars, or read the full feature article on pages 16-17 of this year’s Impact research magazine.

Taking Better Testimony

Young or old, witnesses can be unreliable. “The most important finding is that memory is malleable and reconstructive, rather than an exact replica of any given event,” said Deryn Strange, a professor of psychology. Adult memories, especially when recounting traumatic experiences, can change over time and with the introduction of new information. Memories may incorporate intrusive thoughts, or even warp to include what the individual wishes she did differently.

Strange, who not only does research on memory but also educates courtroom officials, believes that whenever someone’s memory is on trial, judges, juries and lawyers all need to understand the power and limitations of human memory. Otherwise, decisions of guilt or innocence may very well be incorrect and unjust.

Kelly McWilliams, an assistant professor in psychology, focuses her research on children in the witness box, specifically how they use and understand language, and experience memory. Children’s memories are more limited than adults’, and they are susceptible to the introduction of false memories through questioning. Gaining helpful testimony from young witnesses depends more on the questions asked than on their abilities.

Kelly McWilliams, an assistant professor in psychology, focuses her research on children in the witness box, specifically how they use and understand language, and experience memory. Children’s memories are more limited than adults’, and they are susceptible to the introduction of false memories through questioning. Gaining helpful testimony from young witnesses depends more on the questions asked than on their abilities.

McWilliams’s research builds on recommendations from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development — like asking open-ended questions, using general prompts, and more. McWilliams tests new modes of questioning to gather details children might not share in response to an open-ended question, which may be necessary for charging decisions or establishing credibility. “These are practices that take into account what kids are capable of doing and what we should and shouldn’t be asking them to do as witnesses,” she says.

Understanding the Science

Courtroom participants — attorneys, judges, and jurors alike — can often use help determining which pieces of scientific evidence are credible.  Margaret Bull Kovera, a social psychologist by training, has researched this issue for two decades.

Margaret Bull Kovera, a social psychologist by training, has researched this issue for two decades.

Evidence like repressed memories and bite analysis, and even fingerprint evidence, lack a solid basis in science. However, they often make their way into evidence, accompanied by expert witnesses, and parties to a trial may not know enough to challenge them. As a result, “they make decisions that are really not borne out by the evidence, if one were evaluating it properly,” says Kovera.

Kovera’s research is working toward a set of safeguards that contribute to better decision-making. The most promising method is simply to highlight flaws in the evidence during cross examination — something that attorneys can be trained to do — or opposing experts can help provide context. In the end, procedure that relies on solid science helps result in fairer justice.

Open to Interpretation

The quest for fairness doesn’t end at conviction. Post-incarceration, language access is an important part of accessing necessary services and treatment in prison. According to Aída Martínez-Gómez, an associate professor of legal translation and interpreting, incarcerated people who don’t speak the official language of the institution where they are being held face a number of roadblocks. It’s harder for incarcerated people to navigate forms, requests, and services without translated materials. But she says there are promising solutions.

The quest for fairness doesn’t end at conviction. Post-incarceration, language access is an important part of accessing necessary services and treatment in prison. According to Aída Martínez-Gómez, an associate professor of legal translation and interpreting, incarcerated people who don’t speak the official language of the institution where they are being held face a number of roadblocks. It’s harder for incarcerated people to navigate forms, requests, and services without translated materials. But she says there are promising solutions.

Martínez-Gómez advocates most strongly for nonprofessional interpreting services — or services provided by incarcerated peers. In one example from her work, the practice “not only contributed to overcoming the language barrier in the prison, but also to specific rehabilitation goals and potential job opportunities” once the individual’s sentence ended.

In the end, creating a fairer system means using empirical evidence to apply justice accurately and equally in the courtroom and beyond, and to avoid administering justice in arbitrary, capricious, or discriminatory ways. Though these studies can’t solve every inequality, small changes in process and better education of the parties involved can move the needle on basic fairness.

For the full feature, please visit the John Jay Faculty and Staff Research page to read the whole magazine in PDF form!

Research Productivity 2018: A Thread

In June 2019, OAR shared a few of our 2018 most productive scholars with our Twitter followers. Check out the whole thread below, and don’t forget to follow @JohnJayResearch and the researchers mentioned below to get more information in real time!

Last year we recorded more than 700 journal articles and book chapters published by @JohnJayCollege faculty members! While we finish adding up this year’s #JJCResearch productivity, we want to introduce you to some of our most productive #JJCFaculty scholars

First up is @ktwolff11, who also won the 2019 Scholarly Excellence Award and the Donal EJ MacNamara Award for significant scholarly contributions to #criminaljustice! His most recently published article examines patterns of recidivism after a sex offense, find it here: (bit.ly/2XaqWmw)

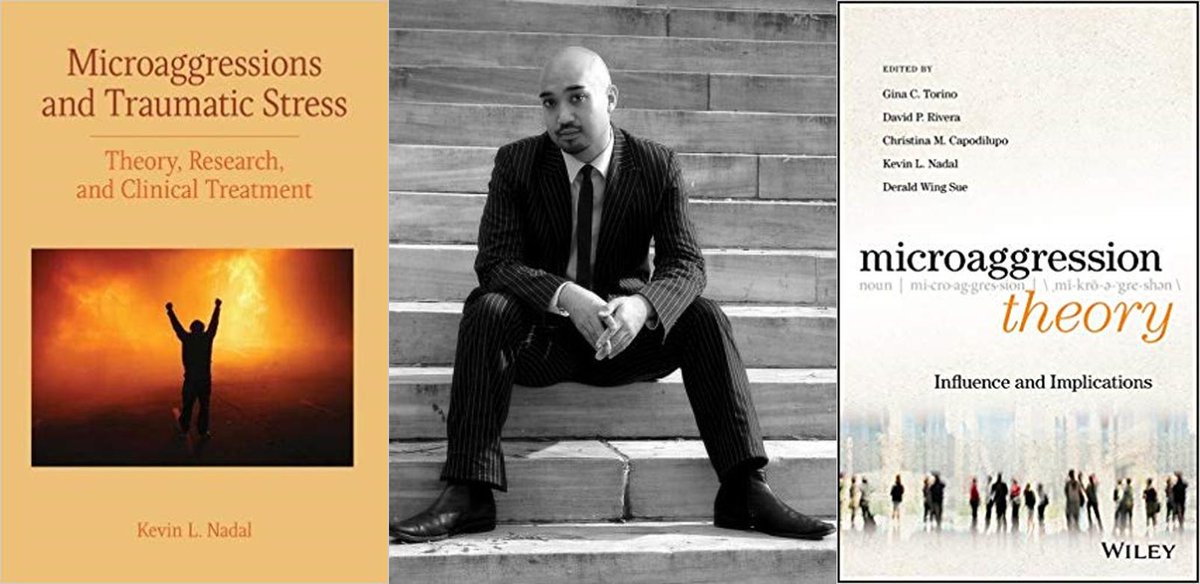

Next is @kevinnadal, @JohnJayCollege professor of psychology and the author/editor of two books in 2018! His research explores the impacts of microaggressions on the mental health of marginalized groups including people of color, women, LGBTQ individuals, & more. #JJCResearch

Today’s ft. #JJCFaculty scholar is @ElizabethJeglic, who published 2 books, 9 peer-reviewed articles, 6 book chapters, and 7 online articles and blogs last year!! Her research focuses on sexual violence prevention — her latest article is in journal ‘Sexual Abuse’ #JJCResearch

Next up is @JohnJayCollege criminal justice prof @PizaEric. Not only is he often featured by the media as an expert on policing matters, but he published 13 journal articles in 2018 on the data behind risk-based policing, CCTV, and more! #JJCResearch

Do you know @JohnJayCollege poli sci prof Samantha Majic? An OAR #BookTalk alum (), last year she published new book “Youth Who Trade Sex in the U.S.” and has been speaking and writing about the harms of & issues surrounding sex trafficking. #JJCResearch

You can watch her 2014 book talk here: (bit.ly/2KAdH8P)

Last year, @DrMazzula, who is the founder of the @LatinaRAS as well as a @JohnJayCollege prof, kept busy writing and presenting about two key issues: microaggressions, and gender/minority representation in academia. #thisiswhataprofessorlookslike #JJCResearch

And don’t forget Philip Yanos, who in 2018 not only published his book ‘Written Off,’ but also a monthly column in @PsychToday by the same name. His articles, on stigma attached to mental illness, were cited more than 700 times last year!

#JJCResearch

Find his blog here: (bit.ly/2IQ2w9J)

And last but not least, @JohnJayCollege is home to some great podcasts. Check out @indoorvoicespod, @TWOH_VL, @NewBooksPoliSci, @QualityPolicing, @JohnJayTLC on Teaching and Learning, and @lavueltablog. So much to learn about!

Eric Piza is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His research focuses on the spatial analysis of crime patterns, problem-oriented policing, crime control technology, and the integration of academic research and police practice. His recent research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals including Criminology, Criminology & Public Policy, Crime & Delinquency, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Justice Quarterly and more. In support of his research, Dr. Piza has secured over $2.2 million in outside research grants, including funding from the National Institute of Justice. In 2017, he was the recipient of the American Society of Criminology, Division of Policing’s Early Career Award in recognition of outstanding scholarly contributions to the field of policing.

Eric Piza is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His research focuses on the spatial analysis of crime patterns, problem-oriented policing, crime control technology, and the integration of academic research and police practice. His recent research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals including Criminology, Criminology & Public Policy, Crime & Delinquency, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Justice Quarterly and more. In support of his research, Dr. Piza has secured over $2.2 million in outside research grants, including funding from the National Institute of Justice. In 2017, he was the recipient of the American Society of Criminology, Division of Policing’s Early Career Award in recognition of outstanding scholarly contributions to the field of policing. Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

Recent Comments