Home » Posts tagged 'historical research'

Tag Archives: historical research

Q&A With Dr. Suvi Rautio, 2023 John Jay Research Visiting Fellow

In our Q&A series, the Office for the Advancement of Research (OAR) is excited to spotlight the 2023 Visiting Research Fellow, Dr. Suvi Rautio for the vital research she has conducted. Suvi is an anthropologist specializing in urbanization and transnationalism in rural China. Guided by family history stories, she delivered a public lecture to the John Jay College Community on April 4, 2023, titled: The Love Letters: Dreams at the Dawn of the Mao Zedong Era.

In this Q&A, Suvi shares her experience as a Visiting Fellow at John Jay College, discusses the research projects she’s worked on, and offers academic advice.

Tell us about your career path?

I started my career path in Beijing, China, working on a large range of different jobs, most of which were completely disconnected from academia and anthropology. Having grown up in Beijing, I had always been concerned in the impact that China’s breakneck development was having on the environment. I grew increasingly curious in the experience of environmental loss – in particular, how this loss alters people’s sense of belonging. This curiosity led me to work for Greenpeace where I led a research team to understand what forms of messaging and campaign strategies resonates with the broader Chinese audience. This felt exciting and meaningful, but it also did not feel like I was doing enough. I was seeking answers to bigger questions. Eventually I understood that I needed to return to academia to attend to my curiosity.

When I started a PhD in anthropology, my research in Southwest China steered me away from questions on the environment to cultural heritage. Although I was no longer focusing on environmental change, my interests in place-making and belonging have remained central to my research. To this day, my anthropological analysis pursues to find answers to how people’s connections to place and belonging change when they experience a sense of loss in one form or another.

What shaped you on your journey to follow your family’s history?

I always knew I wanted to do research on my family history. Growing up in Beijing, I wanted to understand what my family members experienced during the Maoist era — a time in which China was a very different country from the one I was familiar with. My family members did not share or openly speak about stories of the past spoken. Something inside of me has always wanted to understand and peel the layers of my family’s silences.

Maybe a part of this drive was to understand my father’s story growing up in Beijing, which I thought might help me make sense of some of the feelings that I was experiencing living in Beijing. I have always been a bit torn by the experience of feeling a deep association towards a city that I spent most of my childhood and early adulthood but where I am at the same time treated and seen as a foreigner and thus an outcast of the wider Chinese public society. Maybe if I can understand how these processes have been experienced through the lives of my family members, I can also find explanations for my own.

At the beginning, I was unaware that studying my family history was something that I could do as an anthropologist. I thought a study on my own history would appear too self-centered, and of little interest to outsiders. It was only when I was exposed to Alisse Waterston’s work (through Paul Stoller) did I learn that this is not the case. Alisse’s work has been and continues to be fundamental in shaping my journey conducting an intimate ethnography on my family.

My previous research was also fundamental in paving the path to studying my family history. Before my PhD research, I would not have been ready to pursue research on my family history. Academia is structured around critical thinking and critique, and I was scared of having to face that critique on something that is so personal. I was not ready to attend to that. Little did I know that my PhD would also become very personal, and in my dissertation I was very honest about the intimate relationships I formed with my interlocutors. This intimacy has been faced with critique. Rather than silencing those intimacies, writing about them has helped me gain a level of professionalism and courage as a writer and anthropologist. Most importantly, as an anthropologist, I have grown to understand that my research projects tends to get very personal very fast. I now understand that rather than fearing that feeling of intimacy, it is something I need to come to terms with.

Why did you want to share your story with the John Jay Community?

It was such an honour to be invited to share my work at a college-wide lecture with the John Jay Community. I wanted to take the opportunity to share my story and to challenge myself by presenting some initial material I have been collecting on my project. Sharing my story in front of my students and peers felt meaningful and I am very appreciative of the opportunity that was offered to me.

Based on the love letters you shared with us, what does love mean to you?

Love is about offering our thoughtful attention and care to someone or something. The stories that unfold in the love letters has taught me that. I think this quote, which I mention in my talk written by Armi, my grandmother, in her letter to my grandfather epitomizes how unrestrained love should be:

“Love is about whether we can understand and appreciate each other, and whether we are able to speak the same language of heart. And if we don’t understand each other in the beginning, we must be able to show that we can give the other an opportunity for mental liberty and give up our own ideas if we feel we are wronged.”

How does the love letter lecture at John Jay differ from other events you discussed?

I often present my work at conference panels and am more familiar with presenting my work within the time constraints of 10 to 20 minutes. Presenting at John Jay offered a rare opportunity to share my work beyond these time constraints. I also really appreciated having time for questions from the audience. For me, it’s these moments hearing about how my research engages with others that makes academic events, such as the one that John Jay offered me, so meaningful and worthwhile.

Overall I was really impressed by how well organized the lecture at John Jay was – from the preparation of the food and drinks, to the marketing and promotion, and all the other backend work that Remmy Bahati worked hard to put together. I was also impressed that the college had organized a professional video producer to film the lecture. Justin Thomas, the producer did a great job at this.

How did the speech make you feel?

I was so nervous about my presentation before the event. When it was over, a wave of relief swept over me when the audience showed so much enthusiasm and support towards my project. It was also moving to hear how my presentation resonated with audience members. This gave me a big boost of energy to continue moving forward with my project. Overall, the event gave me confidence to continue to seek opportunities to discuss and share my work.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Thank you John Jay for this opportunity to share my work!

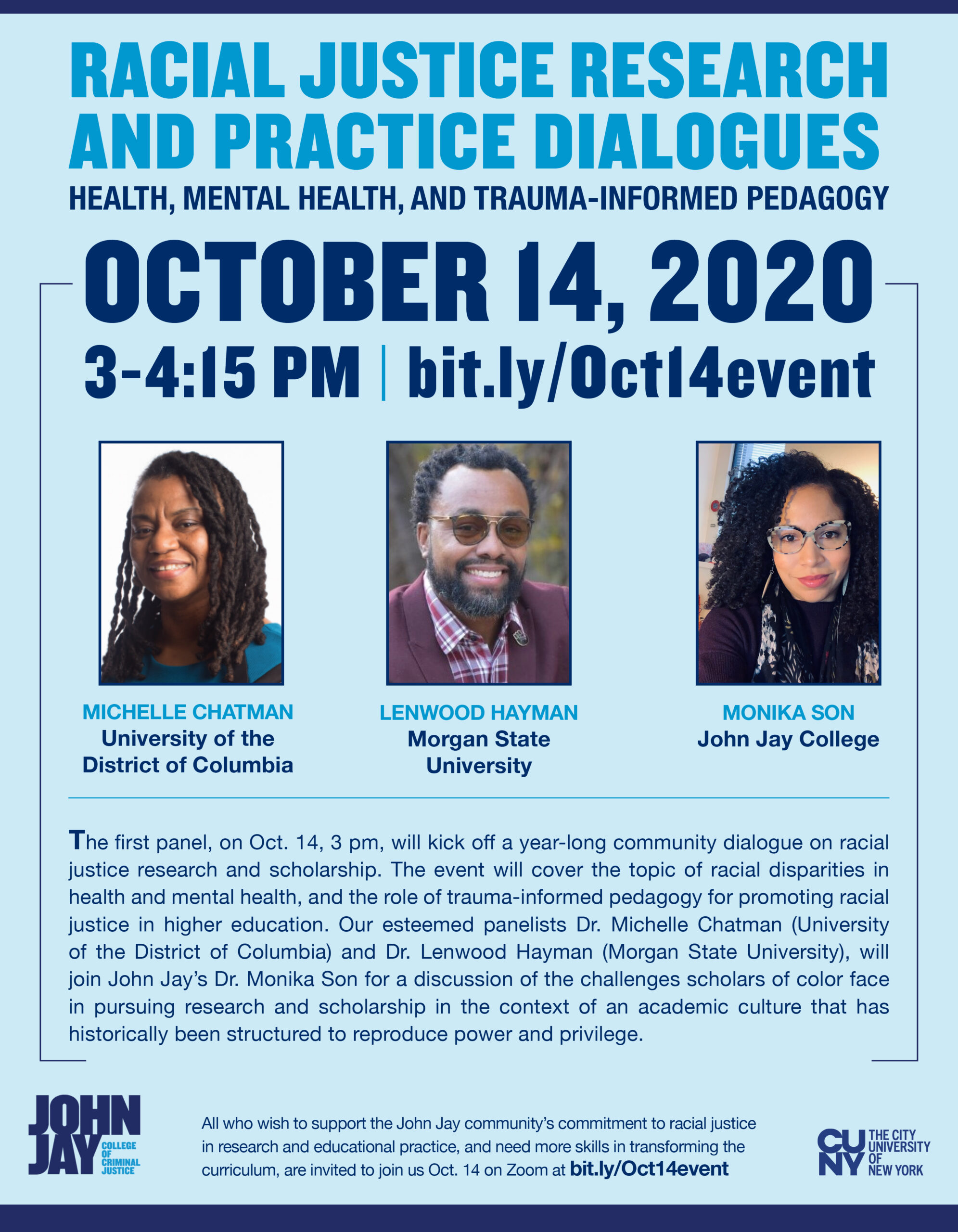

Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues 2020-23

The Office for Academic Affairs through its Office for the Advancement of Research, in collaboration with Undergraduate Studies and a faculty leadership committee representing Africana Studies (Jessica Gordon-Nembhard), Latinx Studies (José Luis Morín), and SEEK (Monika Son), sponsored a year-long community dialogue on racial justice research and scholarship across the disciplines. John Jay College faculty, students, and the broader community were invited to join four panel discussions and four hands-on workshops that invited a more in-depth discussion about changing the ways we teach and learn – specifically, by facilitating meaningful engagement with scholarship by and about people of color, and promoting the incorporation of research on structural inequities into curriculum college-wide. Over the course of the 2020-2021 academic year, events covered multi-dimensional topics including:

- racial disparities in health and mental health and trauma-informed pedagogy;

- the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative;

- economic inequality; and

- racism and discrimination in the criminal legal system.

Each panel was facilitated by a John Jay faculty member who also led a follow-up workshop intended to engage participants more deeply in the subject matter and promote best practices for cultivating racial justice in our classrooms and around the college. Each panel was recorded, and the recordings can be found below, as well as resource guides for further self-guided learning and curricular reform.

Series events, recordings and resources

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Panelists: Dr. Michelle Chatman (UDC) & Dr. Lenwood Hayman (Morgan State University)

Facilitator: Dr. Monika Son (JJC)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/NYTxARHOALw

Resources:

- Ayers, W., Ladson-Billings, G., & Michie, G. (2008). City kids, city schools: More reports from the front row. The New Press. Introduction, pgs 3-7.

- Chatman, MC. (2019). Advancing Black Youth Justice and Healing through Contemplative Practices and African Spiritual Wisdom. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 6(1):27-46.

- Monzó, L. D., & SooHoo, S. (2014). Translating the academy: Learning the racialized languages of academia. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(3), 147–165. DOI: 10.1037/a0037400

- Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Arch of Self, LLC, https://www.yolandasealeyruiz.com/archaeology-of-self

For additional suggested readings, prompts for discussion, and curricular resources, download our full event guide: RJD Event 1.1 Homework and Readings.

Event #2: Race and Historical Narrative — Correcting the Erasure of People of Color

The second panel in the OAR/UGS Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues series, on November 11 at 3 pm, will shine a light on the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative commonly taught in the United States. This erasure is harmful to students of color in particular, as they do not see themselves represented in the stories told about this country, and actively harms people of all races by failing to present an accurate picture of the country’s founding and history.

Panelists: Dr. Paul Ortiz (UFL) & Dr. Suzanne Oboler (John Jay College)

Facilitator: Dr. Edward Paulino (John Jay College)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/WRIDHIA_a94

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the RJD Event 2.1 – Readings.

Event #3: Economic Inequality and Wealth Disparities

Panel Discussion – March 24, 2021, 4:30 – 5:45 pm

Panelists: Dr. Naomi Zewde (CUNY SPH) & Dr. Stephan Lefebvre (Bucknell University)

Facilitator: Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard (JJC)

Event Recording: https://youtu.be/_lp93i3EHqE

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Economic Inequalities – Resources.

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Panel Discussion – April 21, 2021, 3 – 4:15 pm

Panelists: Dr. Jasmine Syedullah (Vassar College) & Professor César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández (University of Denver, Sturm College of Law)

Facilitator: Professor José Luis Morín (JJC)

Recording: https://youtu.be/OZ8N-c7Gob0

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Resources – Racism in the Criminal Legal System

The series continued in academic year 2021-2022, expanding the scope of the discussions with panels on racial equity in disaster recovery.

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

The fifth panel took place on November 1, 2021, and addressed the interdependent roles of government agencies, community-based and non-governmental organizations in promoting or hindering equitable outcomes in post-disaster situations. Panelists included Kim Burgo (Catholic Charities), Craig Fugate (One Concern), Dr. Jason Rivera (Buffalo State College), Dr. Warren Eller (John Jay College), and Dr. Dara Byrne (John Jay College). Find the recording at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQkjxw6RcKg.

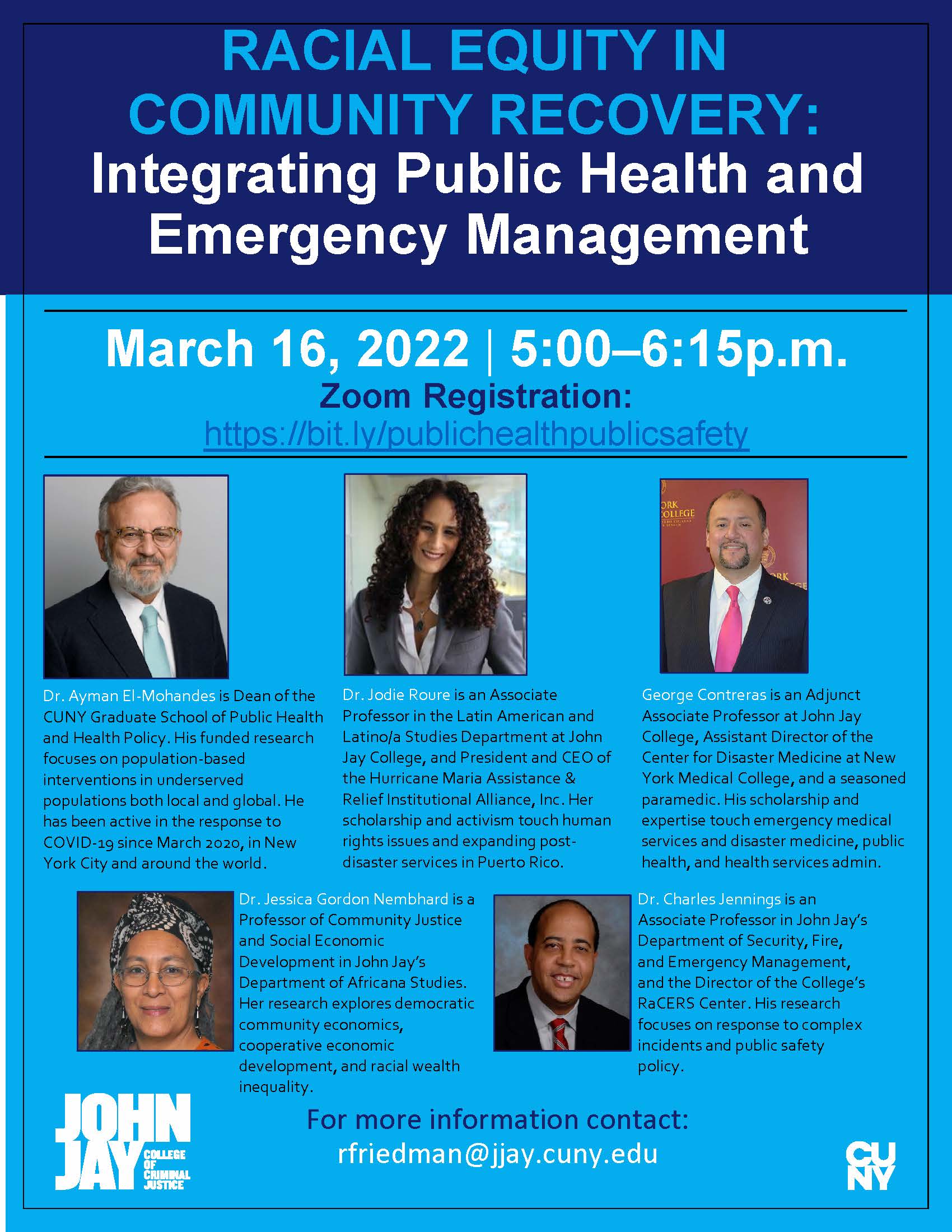

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

The sixth panel in the series, which took place on March 16, 2022, continued the theme of racial equity in disaster recovery. Panelists explored the overlapping roles of the institutions of public health and public safety in promoting equitable outcomes in post-disaster recovery, addressing the intersectional challenges faced by people of color and other marginalized communities. The conversation took special note of the particular context of post-COVID recovery. The participants were Dr. Ayman El-Mohandes (CUNY Graduate School of Public Health), Dr. Jodie Roure (John Jay College), and George Contreras (New York Medical College, John Jay College). The moderators were Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard and Dr. Charles Jennings (John Jay College). A full recording of the event is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4u9wUyjr5Sg&list=PL-B85PTQbdJj5UJhqiddjs1_9p90pZXTZ&index=6.

Resources:

- , 2020: COVID-19: A Barometer for Social Justice in New York City, American Journal of Public Health

- El-Mohandes, A., White, T.M., Wyka, K. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adults in four major US metropolitan areas and nationwide. Sci Rep

- Roure, Jodie G. The Reemergence of Barriers During Crises and Natural Disasters: Gender-Based Violence Spikes Among Women and LGBTQ+ Persons During Confinement. Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, pp 23-50, 2020.

- Jodie G. Roure, 2020 presentation: Children of Puerto Rico & COVID-19: At the Crossroads of Poverty & Disaster.

- Jodie G. Roure, Immigrant Women, Domestic Violence, and Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico: Compounding the Violence for the Most Vulnerable. The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 2019.

- Contreras GW, Burcescu B, Dang T, et al. Drawing parallels among past public health crises and COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.202.

Gerald Markowitz shines light on corporate bad behavior

Distinguished Professor of History Gerald Markowitz and long-time writing partner David Rosner, a Professor of Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia University, have been researching industrial pollution and contaminants since the early 1970s. Their first jointly-authored book, Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease in Twentieth-Century America, explored historical evidence of the lung disease silicosis, which is a hardening of the lungs due to inhaling dust found in sand or rock. Thanks to Deadly Dust, Markowitz and Rosner came to the attention of lawyers bringing workplace safety suits on behalf of construction workers suffering from silicosis, launching a long career of research and expert testimony on occupational disease and toxic substances. In the early 2010s, the duo began an investigation into asbestos and asbestos-related disease.

Their work turned up hundreds of articles on the dangers of asbestos, now a watchword for poisons that can lurk in our homes, dating from 1898 to the present. Markowitz and Rosner also referred to corporate records and documents made public through court discovery; a more recent project called ToxicDocs is an open-source, online database of more than 15 million pages of documents related to silica, lead, vinyl chloride, and asbestos that were previously not easily accessible.

Their work turned up hundreds of articles on the dangers of asbestos, now a watchword for poisons that can lurk in our homes, dating from 1898 to the present. Markowitz and Rosner also referred to corporate records and documents made public through court discovery; a more recent project called ToxicDocs is an open-source, online database of more than 15 million pages of documents related to silica, lead, vinyl chloride, and asbestos that were previously not easily accessible.

In June, Markowitz’s expertise was featured prominently in the American Journal of Public Health, in an article detailing a representative episode in the history of the struggle between industry and regulators. In “Nondetected: The Politics of Measurement of Asbestos in Talc, 1971-1976,” Markowitz and his co-authors describe the years-long interval between the talc industry’s acknowledgement that asbestos is toxic and their taking action to protect consumers, and the subsequent conflict between the Conflict, Toiletry, and Fragrance Association (CTFA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) over regulating appropriate methods for detecting asbestos contamination in consumer talc products and setting safety standards.

The focus of the article, said Professor Markowitz, “was that the cosmetic industry, I think very consciously, used this concept of nondetected, which we as consumers think of as ‘no asbestos in the talc,’ but nondetected could mean enough asbestos in the talc to cause disease. And that’s what the industry understood, but consumers did not.”

The CTFA’s 1970s victory in lowering detection standards and advocating for self-regulation is still bearing fruit; recent lawsuits against talcum powder manufacturers allege the household product causes cancer due to asbestos contamination. As recently as 2018, courts awarded plaintiffs record damages of close to $4.7 billion in a case against manufacturers, capturing public attention.

We sat down with Professor Markowitz to talk about his work researching industrial poisons and about corporate responsibility to the consumer in today’s world. Read on to hear from Professor Gerald Markowitz in his own words.

Why do you believe that talc product manufacturers continued to accept a lower standard for asbestos eradication despite known health dangers, not to mention the risks of litigation?

When they developed this idea, in the 1970s, their basic argument was that there should be as little federal regulation as possible. [The CTFA] was able to lobby the federal FDA that the technologies that the FDA was proposing were not able to be completely accurate, would give too many false positives, would take a long time to do, and would be costly. So they proposed their own method. And they’re able to eventually convince the FDA that it should not be federal but industry regulation.

But what they admit privately is that their method, which is not as demanding as the FDA’s proposed method, was not necessarily accurate and was not necessarily consistent. So to a certain extent, they were really able to forestall regulation by claiming that they could do as good a job [of detecting asbestos in talc products], even though they themselves admitted that they could not do as good a job. And by the very nature of their method, they were going to uncover much less asbestos than the FDA’s method was capable of uncovering.

Do you think there’s something special about the current moment that made this article of particular relevance?

I think it was the variety of ways that deregulation has had an impact on the health and welfare of people in the United States and other parts of the world. To the extent that these articles could help to call attention to that happening, they are important. The advantage of history is that we are able to really see the process unfold in a kind of detail that we don’t necessarily have in observing regulatory of anti-regulatory actions taking place at the moment we’re living in. That level of detail I think is instructive in terms of being able to understand how similar things could be happening today.

Would you like to see this history galvanize some kind of action?

The most important thing that can happen is that people really have to take politics seriously. The United States has a long history of mass movements really demanding and achieving fundamental reforms. Just going back to the 1960s, the demand for civil rights, the efforts of people to get voting rights for African Americans, that didn’t happen simply because Congress decided to pass a law; people were demanding it in mass actions. These are really instructive in terms of what can happen today, and even what is happening today.

Pieces accompanying your article in the AJPH, such as the one by former Assistant Secretary of Labor for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration David Michaels, suggest that corporate influence is getting stronger, to the detriment of consumer and public health. The current administration has loosened or degraded regulatory standards for a variety of products — should we expect more legal battles down the line?

Yes, absolutely. Since the 1970s there has been a very sustained effort by many businesses to oppose regulation, and you get the classic statement by Ronald Reagan, when he said that ‘government isn’t the solution, government is the problem.’ I think the legacy of that, of the push for deregulation as a means of stimulating the economy and freeing business to innovate and all of those kinds of ideas, I think the legacy of that is going to be a variety of problems, not only in consumer products but in environmental damage. It’s going to be for workers, for consumers, for people living in communities where toxic substances are going to be released, we’re going to be suffering those consequences, and the unfortunate thing is that it’s only going to be remedied in retrospect.

And to add one other element, we know that the burden, especially of environmental pollution, toxic waste, global warming, is going to affect poor communities and communities of color to a much great extent than richer communities. At a college emphasizing social justice, this becomes an even more vital issue.

Are there other consumer products known to include dangerous adulterants that are similarly being ‘underregulated?’

BPA [bisphenol A, a chemical used to make certain plastics since the 1960s] is one example; a lot of household cleaners and flame retardants are another one. We’ve discovered that flame retardants are extremely dangerous to people, and that people have them in their bodies. Formaldehyde is another one; there was a scandal about formaldehyde in temporary housing given to people after Katrina, that was unsafe.

There are lots of things we have clues about, but the real scandal is that chemicals are being produced and we’re using them in very large quantities, that have never been tested. And in the United States we have this philosophy, innocent until proven guilty. It’s the same philosophy with chemicals — they are innocent until proven guilty. The Europeans have a system, chemicals can’t be introduced until they’re proven safe. It’s a basic difference in philosophy that companies need to prove that something is safe before they can experiment on us and ensure it doesn’t cause cancer. But in the United States they say that if it does cause cancer, we’ll take it off the market, but that’s very difficult to prove and you’ve done the damage already.

You note in your article that talc researchers were disappointed when their work became known to the industry, but that ‘nothing was done until the results became public.’ Do you think it remains true in cases of corporate wrongdoing that nothing is done until the public finds out all the information?

In the 1970s, there was this wonderful act passed called the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). The fundamental principle behind that was that if you shine the light of publicity and information and people have that, then they have the ability to act in their own interests. One contribution that historians can make is, using the older historical records, we can cast a light on activities and attitudes and actions that permit people to see what is going on and demand change.

Gerald Markowitz is a Distinguished Professor of History in the Interdisciplinary Studies Department at John Jay College and the Graduate Center of CUNY. His research focuses on the history of public health in the 20th century, environmental health, and occupational safety and health. He has authored a number of books, most recently Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of America’s Children, also in cooperation with David Rosner.

Recent Comments