The following piece gives notes for the ongoing research by Dr. Veronica Michel, an Assistant Professor of Political Science. This research evaluates criminal procedure cross-nationally to examine victim’s rights in Latin America. It was originally posted in 2017.

For almost a decade I have been doing research on victims’ rights in Latin America. My interest in this topic began because while conducting research for my dissertation at the University of Minnesota I learned that victims of crime in most Latin American countries are granted a very interesting procedural right: the right to private prosecution within criminal proceedings.

I have explained in some of my previous publications (for instance, in this co-authored article with Kathryn Sikkink), that the right to private prosecution goes well beyond a victim’s right to speak granted in the US because the right to private prosecution grants the victim the right to participate with a lawyer in the prosecution of a crime. As interesting and important as private prosecution is for access to justice (and it is, as I argue here, here, and also in a forthcoming book), in Latin America victims of crime are granted many other rights. For instance, victims have strong reparation rights, like the right to introduce a civil claim within a criminal proceeding, also known as a civil action; and victims are also granted important protection rights, like the right to be informed about the state of the proceedings or the right to be offered shelter or protection when needed.

A content analysis of the current criminal procedure codes in 17 civil law countries in the region shows that these statutes provide quite a vast array of rights to victims of crime. What I find fascinating, however, is that all these rights are quite new. Yes, victims have always existed as long as crime has been around. But “victims’ rights” as such are quite new. As you can see in the Word Cloud above, an analysis of these 17 current criminal procedure codes reveals that among the most used concepts in these statutes we find the words “victim” (víctima) or private prosecutor (querellante).

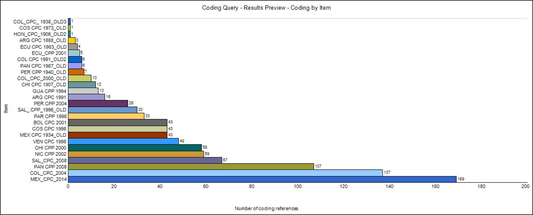

Moreover, a closer comparison of old and current criminal procedure codes also reveals that the more recent a statute is, the more references to “victims” it makes. Some old criminal procedure codes did not even include the word victim in the whole statute. For instance, the criminal procedure codes of Nicaragua of 1879 or even the one of Honduras from 1985, did not even once mentioned the word victim.

In contrast, since 1994 we have witnessed an expansion of victims’ rights in criminal procedure. For example, Mexico’s previous criminal procedure code of 1934 only mentioned the word victim twice. In sharp contrast, its latest statute which entered into force in 2014, mentions the word 169 times!

So where do these “victims’ rights” come from? Why is it that countries gradually embraced the “victim” and began to expand the rights granted to this actor? Why is it that most countries in the region today provide all these similar rights? These are the questions that I am now exploring in an article that aims to explain how Latin America came to have such a vast array of rights for victims. So, stay tuned. I will report soon a summary of my findings in this blog.

Recent Comments