John Jay Research Blog

The Office for the Advancement of Research, as part of our Public Scholarship Initiative, actively solicits blog entries from John Jay faculty, staff, and external scholars working on issues of key contemporary and historical significance. We promote these entries on social media, including Facebook and Twitter, as well as within the university through a partnership with our Marketing and Development Office. If you wish to contribute an entry, please contact Research Communications Specialist Remmy Bahati at rbahati@jjay.cuny.edu with a brief (1-2 sentence) summary of your proposed entry.

John Jay Scholars on the News: What Makes for Smarter Gun Policy?

John Jay Scholars on the News looks at tough issues through the lens of the research our scholars are producing, and informs the way we think about important debates and the role of public scholarship and evaluation. This post was originally published on March 19, 2018.

Following the mass shooting that killed 17 and injured even more at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida – just the latest high-profile incidence of gun violence in the United States – the conversation in Washington has focused heavily on gun policy. Thanks in large measure to the efforts and activism of MSDHS students since the attack, the issue has remained at the top of the national agenda. On March 14, students from schools around the country walked out of classes to protest widespread gun violence, and protests have taken to the Capitol and state houses to ask for change.

We spoke to scholars and practitioners at John Jay College to ask for their thoughts about what feels like a significant moment in the public discourse on gun policy, and asked how best to move forward.

How does this moment in the national conversation about gun control feel different? Why do you think the response to the Parkland shooting has been so different from previous events? Do you believe the Never Again movement has the potential to make real change?

Christopher Herrmann (Assistant Professor, Law and Police Science): There is certainly a different ‘feel’ about the gun control debate after the Parkland shooting.

Sung-suk Violet Yu (Associate Professor, Criminal Justice): The Never Again organizers are very active. The movement has gained traction, I think, because it is high school students leading it. They are not too helpless (like the young children at Sandy Hook), but also are not jaded, and they have few opponents. They are soon-to-be voters and a soon-to-be major consumer group, whose political views and spending habits are flexible and can be changed, making them a force to be reckoned with. They challenge mindsets and business-as-usual attitudes of politicians and big companies alike.

The organizers are also passionate, and savvy about social networks, and their message resonates with many because the organizers experienced the carnage of school shootings firsthand, and we have all witnessed such tragedies too many times.

Doug Evans (Senior Investigator, Research and Evaluation Center): Emotional appeals hit hard when they come from people who have lived through a difficult experience, and even harder when they come from kids. The high school survivors are motivated and have a platform to address the masses, and people are listening because they can relate, either because they are in high school or are a teenager, or because they have kids of their own. I think the Never Again movement will make real change, but it will be gradual. As more and more young people become involved and realize the collective influence they can have over elections, elected officials will have no choice but to adjust their campaigns to appeal to a younger voting demographic.

Christopher Herrmann: The Never Again movement has already managed to keep an ongoing dialogue on current gun politics and organized nationwide student walkouts, and soon there will be the National March for Our Lives on March 24th in Washington, DC. The question remains if these tactics will contribute to measurable change in the future. So far I think the biggest accomplishment the movement can take credit for is the recent gun bill passed into law in Florida (Senate Bill 7026, also known as the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act). While it didn’t accomplish all the gun control measures that were requested, the fact that students and supporters were able to make substantial legislative changes to Florida’s gun laws within three weeks in one of the most pro-gun state legislatures is momentous and noteworthy.

What issues are we losing sight of or glossing over when we talk about mass shootings? How do we take a broader view of gun violence when mass shootings in schools are dominating the news cycle?

Doug Evans: This cannot be stated enough: the NRA has an annual budget of a quarter billion dollars, and often uses an extreme argument (the government wants to take your guns and, ultimately, your rights) in response to reasonable arguments (restricting who can own guns and automatic firearms to prevent mass shootings). Coming to a consensus about the purpose of weapons that can fire ten or more rounds per second and deciding who, if anyone, should have access to these weapons that are capable of causing mass casualties, requires us to take a broader view.

Christopher Herrmann: Using 2015 data from the mass shooting tracker website massshootingtracker.org, we see there were 372 mass shootings in the United States, causing 469 gun fatalities and injuring an additional 1,387 victims. Compare those mass shooting numbers to broader gun violence deaths – there were 36,252 firearm deaths in 2015, comprised of 22,018 suicides, 12,979 homicides (which includes the 469 mass shooting fatalities), and 1,255 ‘other’ gun fatalities. The below chart shows that mass shootings make up less than 2% of all firearm-related deaths in 2015; moreover, school shootings are a very small percentage of mass shootings.

While the media may focus on mass shootings (especially school shootings), our gun politics debate needs to take into account the much larger context of suicide and homicide firearm deaths.

David Kennedy (Director, National Network for Safe Communities): When these mass shootings in schools occur, the public is rightfully outraged, but they are rarely as outraged by the gun violence that regularly causes trauma, fear, and grief in other communities. This is a problem, but also an opportunity to draw wider attention to the routine violence taking place in many marginalized communities. People should know that while we wait for broad solutions for preventing mass shootings, we already have immediate ways for states and cities to address this more frequent violence.

What gun restrictions or legislation, short of a ban, would be the most effective in reducing gun violence?

Violet Yu: It is not that we not know how to have sensible gun control. The simple sad fact is that there is a lack of political, ideological and economic willpower to make this happen. It is startling how easy it is to be a gun owner. At least in the U.S., if you can afford a smartphone, you can afford a semi-automatic rifle. Once purchased, there are minimal to no ongoing maintenance expenses. This affordability allows a large number of people to own multiple firearms, and practice shooting or hunting as hobbies.

It is not a new idea to suggest registering all firearms with an agency, similar to drivers’ licenses. What about mandatory gun owner’s insurance, as expensive as motor vehicle insurance or even a mobile phone subscription? That ongoing expense would remind gun owners that they must take good care of their firearms and not let them fall into the hands of non-legal owners. It is not clear whether a measure placing an artificial economic burden on gun ownership will pass, but we have done this before by levying taxes (i.e., alcohol) or giving tax credits or subsidies as needed. Would it be crazy to add a tax on firearms? I think not.

Christopher Herrmann: I along with the overwhelming majority of Americans (including an overwhelming majority of gun-owning Americans) support a universal background check system that requires all firearm sales to go through a licensed firearms dealer, including private party and gun show transactions. I also support improving the current FBI National Instant Criminal Background Check System, to incorporate any military violations and mental health screenings into the current system, and bans on assault-style weapons and bump stocks. I support a waiting period on prospective gun buyers between three and five days. And I do not advocate arming school employees.

Doug Evans: Although policymakers would like the public to think that legislation is responsible for falling rates of gun violence [in New York City], I think that is an oversimplification. It may be responsible for a small percentage of the reduction, but large cities across the country are in the midst of historic decreases in crime and violence. More prominent than legislation are economic and sociological factors.

Nevertheless, there do need to be restrictions on people with mental illness, both for the protection of the public and would-be gun owners.

What states do you believe provide the best model for potential new national legislation?

Doug Evans: Specific gun laws vary widely not only from state to state but also within states. New York City has experienced decreasing gun crimes and the lowest number of murders in decades, as I noted earlier, but the city’s gun laws are stricter than most jurisdictions would consider implementing. It is extremely difficult to get a gun permit and even more difficult to get a license to carry a gun. Open carry of guns is not allowed anywhere in New York. The considerable paperwork, fees, background checks and additional steps New York has put in place for gaining legal access to guns are far more onerous than most states.

Christopher Herrmann: The governors of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and Rhode Island recently signed an MOU that will create a multi-state regional task force on gun violence. The objective of the task force is to (1) trace and intercept illegal guns; (2) improve data-sharing, analysis, and response efforts; and (3) establish a multidisciplinary gun violence research consortium containing researchers from criminal justice, public health, public safety, public policy, and social welfare. President Mason, David Kennedy and I were recently included on a conference call and invited to participate.

The federal government, however, has been unable to dedicate a significant research focus on gun violence and has been largely ineffective in developing policy that improves upon any of our current gun violence problems.

(Answers have been lightly edited for clarity.)

Doug Evans is an adjunct assistant professor at John Jay College, and a Senior Investigator/Project Director at the college’s Research and Evaluation Center. He is currently engaged in an assessment of a system-wide effort in New York City to expedite and enhance arrests, prosecutions and sentencing in felony firearm cases.

Doug Evans is an adjunct assistant professor at John Jay College, and a Senior Investigator/Project Director at the college’s Research and Evaluation Center. He is currently engaged in an assessment of a system-wide effort in New York City to expedite and enhance arrests, prosecutions and sentencing in felony firearm cases.

Christopher Herrmann is an assistant professor in John Jay College’s Law and Police Science Department. He specializes in crime analysis and crime mapping, and has worked with the NYPD on crime prevention and control strategies. Currently he is working on violence prevention initiatives with the New York City Housing Authority research team at John Jay, concentrating on gun violence in New York City.

Christopher Herrmann is an assistant professor in John Jay College’s Law and Police Science Department. He specializes in crime analysis and crime mapping, and has worked with the NYPD on crime prevention and control strategies. Currently he is working on violence prevention initiatives with the New York City Housing Authority research team at John Jay, concentrating on gun violence in New York City.

David Kennedy is a professor of criminal justice at John Jay College, and the director of the National Network for Safe Communities. His work with the NNSC supports cities implementing strategic interventions to reduce violence, minimize arrest and incarceration, enhance police legitimacy, and strengthen relationships between law enforcement and communities.

David Kennedy is a professor of criminal justice at John Jay College, and the director of the National Network for Safe Communities. His work with the NNSC supports cities implementing strategic interventions to reduce violence, minimize arrest and incarceration, enhance police legitimacy, and strengthen relationships between law enforcement and communities.

Sung-suk Violet Yu is an associate professor in the Criminal Justice Department at John Jay College. Formerly of the Vera Institute of Justice, she focuses on crime prevention, corrections, and impacts of environments on spatial patterns of crime using statistical methods. Her upcoming article in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence is “Illegal Firearm Availability and Violence: Neighborhood Level Analysis.”

Sung-suk Violet Yu is an associate professor in the Criminal Justice Department at John Jay College. Formerly of the Vera Institute of Justice, she focuses on crime prevention, corrections, and impacts of environments on spatial patterns of crime using statistical methods. Her upcoming article in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence is “Illegal Firearm Availability and Violence: Neighborhood Level Analysis.”

John Jay Scholars on the News: What Explains Falling Urban Crime Rates?

The following piece is the first in a series of interviews with faculty on their responses to questions making a big impact in the news. John Jay Scholars on the News looks at tough issues through the lens of the research our scholars are producing, and informs the way we think about important debates and the role of public scholarship and evaluation. It was originally published on January 17, 2018.

After a year or more of heated rhetoric around ostensibly rising rates of violent crime in many American cities, recently published statistics showing crime rates in some of these cities falling sharply have captured the attention of policy makers and academics alike. Subsequent discussion in the public sphere has tried to link policing strategies to these reductions in crime; in New York City, for example, some of that discussion has looked at the cessation of stop-question-frisk policies in New York City and our record low rates of violent crime. Because John Jay is a college with a unique focus on policing and criminal justice-related issues, we reached out to some of our faculty and staff to find out what they think is causing crime rates to drop, and whether police forces can take some of the credit.

To start, we talked with Associate Professor Eric L. Piza from the Department of Law and Police Science. He was careful to begin by qualifying his answer, reminding us that the real world isn’t controlled like an experiment, but went on to suggest that proactive, evidence-based policing strategies the NYPD began in the ’90s may have contributed to recent declines in crime rates.

It’s always tough to attribute precise credit for crime declines. The real world isn’t a laboratory, so we can’t

Department of Law & Police Science

carefully control conditions and isolate causal mechanisms. But with that said, looking at policing research suggests that the NYPD deserves some credit for the crime reduction. Research evidence suggests that proactive, focused policing has a much greater impact on crime occurrence than reactive policing. Importantly, the de-commitment from stop-question-frisk did not spell the end of proactive policing in NYC. Rather, the NYPD has revamped their processes to emphasize team policing and enhance community engagement. Projects such as Cure Violence and Focused Deterrence have also dedicated additional resources to focus on the highest risk offenders and neighborhoods experiencing disproportionate levels of gun violence.

Expanding the focus to the historical crime decline, I think there’s also evidence to support the influence of police. When Commissioner [William] Bratton first arrived at the NYPD in the early 1990s, the rapid pace with which the agency deployed Broken Windows policing tactics left little time for the type of controlled evaluations that could rigorously test their influence. However, we now have ample research evidence to say that Broken Windows is indeed an effective crime reduction strategy so, in hindsight, I think we can say that the NYPD deployed an evidence-based crime reduction strategy in the 1990s.

We also reached out to Meaghan McDonald, Director of the Group Violence Intervention strategy at the National Network for Safe Communities. She broaded our perspective, highlighting strategies that are working in cities around the country, not just in New York.

Cities as different as Detroit, Newburgh [NY], New Haven and New York City have significantly reduced or maintained historically low levels of homicides and shootings over the past year. They did so in part by doing what we know can work: focusing law enforcement, community influence, and support and outreach resources for the people who are most likely to be the victims and perpetrators of violence.

People in groups — gangs and crews — are disproportionately involved in serious violence, and when police and communities concentrate their efforts on keeping these people alive and out of prison, they can maximize ROI [return on investment]. Agencies focusing on group violence are recognizing the power of advance communication to this population and, when a law enforcement response is necessary, making sure it is focused and legitimate.

When cities take this approach, they have a greater chance of fundamentally changing the dynamics of violence in their city.

Lest we feel overconfident about attributing causation, we were left with a word of caution from Jeffrey Butts, the director of the Research and Evaluation Center, that should guide all John Jay scholars whatever their field of study.

Research & Evaluation Center

When asked about fluctuating crime rates or differences in crime between cities, a genuine scholar starts with a raised eyebrow or furrowed brow and then goes on to describe various other factors that could be contributing to the difference. Researchers — as opposed to politicians — never point to just one cause. Only after careful investigation of other explanations will a researcher be bold enough to reject the null hypothesis, although they address cause and effect only in terms of ‘explained variance’ or ‘effect size.’

This is why the general public listens to politicians more than they listen to scholars and academics. It’s easier, and can be comforting when someone in authority provides a simple explanation for the frightening uncertainty that surrounds us. Researchers, however, thrive in uncertainty.

(Answers have been lightly edited for clarity.)

“Manufactured” Mismatch: Cultural Incongruence and Black Experience in the Academy

The following piece gives notes on the autoethnography by Criminal Justice PhD students Kwan-Lamar Blount-Hill and Victor St. John, which was the *winner* of the “Best Article Award” by the Awards Committee of the American Society of Criminology Divison on Critical Criminology and Social Justice. This piece voices their shared experience in traditionally non-minority institutions. Click here to view the full article, originally published January 23, 2017.

Autoethnography is still somewhat avant garde in the field of criminology and criminal justice. The notion of a researcher “studying” her or his personal experience and history engenders some skepticism as to a works’ objectivity and, therefore, its value. What this misunderstands is the realization that there is value in the subjective. We, as scientists, also prize objectivity as valuable, but our work has been premised on the idea that subjective perceptions matter. Kwan has focused his study on perceptions of government legitimacy, how the perception of injustice is enough to cultivate cynicism, encourage disobedience, and spark rebellion. Victor has concentrated on how inmate perceptions of architectural features impact their receptivity to treatment, from conscious decision-making to subconscious processes to biochemical reactions at the cellular level. Women and men much more accomplished than us have built long-lasting careers on similar arguments.

“Manufactured ‘Mismatch’” uses autoethnogaphy to explore perception and, in that regard, we believe achieved its goal. In it, we accurately captured our felt experience and argued that it represented a state of feeling that might very well be shared beyond us. Examining our subjective perceptions, we came to understand perceived “mismatch” between us and our environment through the lens of cultural incongruence, where two cultures differ such that coming together causes stress, strain or all-out clash. The two cultures we identified as being, in our cases, at least partially incongruent were “Black culture” and the “culture of criminology and criminal justice.” Exploring the coming together of these two is already made difficult by the paucity of Black academics in the field, specifically coming from majority non-minority institutions. Having no outside resources to assist, we concluded that in-depth study of this population would be impossible for us. It so happens that both of us belong to this demographic and, at any rate, do not our perceptions matter too?

Our hypothesis was that Black culture and the culture of academic criminology might clash on several points. First, we hypothesized that Blacks would see themselves more likely to criticize mainstream institutions than other academics in the field, causing some friction with institutionalists. We hypothesized that Blacks would likely feel more religious or faith-oriented than their colleagues, causing friction with those who espouse faith-free intellectualism. We hypothesized that Blacks would perceive the academy as a much more intimate space, clashing with those see it in the nature of a transactional workplace environment. Finally, we hypothesized that Blacks would feel more inclined to see themselves as members of a collective, rather than emphasize their individual success, of course, clashing with those who feel otherwise. We separately examined our own experiences and perceptions of them, using a combination of record review and recollection to determine whether our hypotheses were supported. We found that they were. Our final hypothesis was that these felt differences would cause cultural mismatch, and that cultural mismatch might be the cause of Black academic struggles, as opposed to the intellectual mismatch that has historically been offered as an explanation.

Autoethnography is valuable because it allows for deep dives into researcher perceptions that create the potential for avenues of further study and, hopefully, for further action. By no means would we argue that our study proves the existence of anything but our own personal feelings about our experience. What we would argue is that it supplies a worthy reason to engage in further study on the topic. This is particularly the case for those who profess to have genuine concern in mitigating these tensions by creating spaces where friction is not quite so palpable or by creating systems that can guide Black students, and others, through it.

Again, autoethnography creates the potential for avenues of further study and further action, though we did not anticipate the many ways it would. One such way was by revealing and explaining our feelings about our experience to colleagues who had not understood them. By writing our thoughts on the page, in the tempered language of scholarship, and allowing other academics to engage with it outside of the tense environment of direct confrontation, we allowed others the time and space to digest our message. We opened the door for later discussions that needed to be had, but were not on track to happen otherwise. Most impactful, thus far, the work generated an invitation to meet privately with a colleague of ours to explore questions that had not been fully explained in our piece. The invitation was a courageous move on the part of a non-Black faculty member who was brave enough to wade into the waters of racial tension and to hold her own. She commended our work, yes, but also challenged us on the conclusions we drew from our perceptual experiences.

As scientists, we have a duty to forthrightly reexamine our interpretations when they are called into question. So, then, we want to take a moment to engage in some reexamination. Having done some of that, we have arrived at a number of additional conclusions. These are, again, based on our own perceptions and are in need of validation through further study. However, our description of incongruence appeared to emphasize how academic culture clashed with Black culture without adequately accounting for the position on the opposite side. We seek to address that here.

Taking our assumption of greater Black cynicism toward mainstream institutions into further consideration, we must admit that this might present a challenge even to those academic institutions that want to be more welcoming. This cultural phenomenon means that Black academics may often come into an institutional situation prepped for unfair treatment. The expectation is not unwarranted – we trust we need not go into the litany of ways that American societal institutions have engaged in discrimination and structural violence towards Blacks over the centuries. Black cynicism can be viewed as a protective adaptation of the culture, though one that leads to Black academics potentially misinterpreting personality disagreements as disagreements about race.

The situation is made more complicated in that some seemingly personal disagreements are actually about race, and our colleagues inability to see this when it happens only adds to our hypersensitivity around the subject and increases our interpretation through a racial lens. Moreover, in our colorblind society, racial tensions are often due to unintentional affronts. Non-Black colleagues will complain that their intentions were not malicious or ill, seeming somehow not to understand that, in the context of a societal arrangement which necessarily disadvantages Blacks, unintentional but ignorant attitudes and actions that perpetuate disadvantage and isolation are as harmful as intentional ones. That great misunderstanding only confirms Black skepticism of institutional environments and further racializes their interpretive lenses.

To further complicate matters, those non-Black colleagues who both understand the inherent challenge of Black success in mainstream institutions – success often coming from the backdrop of multi-generational, socio-structural disadvantage – and who want to be sensitive to those challenges may nonetheless find a mistake of theirs, or a personal disagreement, or a misunderstanding, suddenly characterized as a racial issue by their Black counterparts. When Black academics begin seeing professional interactions along racial – instead of interpersonal – lines, any one-on-one conflict can be transmuted into a battle of the races. Previous experience with racial discrimination or insensitivity reinforces the salience of a racialized perspective, which may then filter truly non-racial encounters through a racialized lens, further reinforcing its salience and possibly creating racial conflict from an interaction where none was originally intended – a cycle manufacturing mismatch.

Other aspects of Black culture beyond cynicism may also drive this. Black collectivism is a prime feature of the culture. For a people who have been oppressed en masse, individual experiences may become so similar that victory and tragedy are seen as shared. We can attest to this. As each other’s only Black male contacts in our doctoral program and then connecting on a shared perception of loneliness, we are now both intimately invested in our collective success. We see a challenge to one as a challenge to both. When Kwan perceives a problem of his as due to his race, we are both mobilized to respond. If Victor encounters a problem, racial or not, to the degree that it may stymie his success, it is still a challenge to us both. Our collective is not made up of just us. More than most of our colleagues, we are sure, our families are dependent on our success, not merely as a point of pride, but as a necessary step toward the family’s unitary economic and social stability. Still more, each time we walk into a classroom, we not only feel the responsibility of a professor to his students, but a responsibility to every Black face in the classroom to demonstrate Black potential and, to every non-Black face, the responsibility of demonstrating Black capability. We feel that we are not just ourselves, we are us all.

That weight may be, in some estimations, unwieldy, unwise and unjustified, but, to us, it is also undeniable and unavoidable. We feel personally proud of Black achievement and disappointed at Black failure because we are not spectators, but that achievement or failure is our own. And for those who point out the problems with such an approach, we retort that it was not one entirely of our own creation. American has consistently dealt with Blacks as if we were one writhing monolith. A rebellion on one plantation elicited punishment within several. Resistance to Jim Crow in one place sparked retaliation in several others. A policeman’s bad experience with one Black person leads to his rough treatment of others. Academics themselves have been guilty of conflating individuals into singularity – our paper explored how perceptions of historical religious ignorance and bigotry have made Black religiosity a mark of unsophistication and anti-intellectualism. Forced into one collective Black box, we cannot be blamed for responding in kind, as we are, for ill or good, all connected. Perhaps unfortunately, this may mean that a sensation misinterpreted as pain in one corner of the Black communal body often reverberates throughout, multiplying its intensity and the nature of the response.

Black cynicism and the adoption of vicarious experience as our own is a recipe for perceiving racial incivility in every corner. Interestingly, the professor we had the opportunity to speak with challenged one of our responses to perceived incongruence. She noted that we had developed a pattern of avoiding the institution due to our discomfort. Upon reflection, we must admit that truth. To paraphrase her point, our abandonment relinquished our claim to a place where we, in fact, belonged and our absence made it difficult for those who actually cared to determine how best to make that space more inclusive. Standing up to decry the isolation that drove us away might be seen as courageous, but fleeing the scene to complain from the outskirts was decidedly not. For this, we must take responsibility.

We would add, though, that many of our colleagues – even those who are well-meaning – have often taken a similar approach, avoiding depth of contact with us in order not to risk unwittingly hitting some racial landmine. Unwillingness to traverse into uncomfortable territory is not tenable for us, but equally untenable for non-Black others. Both harm the prospects for our field’s advancement beyond the “problem of the color-line.” We commit to doing our part in bridging the gap by seeking not to bring distrust where it is not deserved, by discerning the personal from the racial (inasmuch as these can be separated), and by being present. But we must demand, then, that others be willing to acknowledge the realities that breed distrust, and commit to being proactive and helping us to overcome not only our perceptual biases, but, more importantly, the oppressive structures that produce them

One way to do that is to take advantage of another aspect of Black culture that we explored – the search for personal connection. This will make many of our colleagues uncomfortable we are sure. However, when any academic stops to think how much of her or his own success is due to friendships and social ties with others, one must see that personal connection in the profession is not so foreign a concept. We merely suggest that, for those who care, the extra step to achieve closer bonds with Black counterparts on their terms may bring outsized dividends. We have a ready example: At the outset of writing this post, our thought was simply to amplify the message of our original piece. After a conversation with the professor, who we both felt truly cared about us – even if we do not always agree with her counsel – was able to change the tenor of this discussion.

There is no single person in the United States that has not benefitted from the contribution of Black American people, even if only indirectly through recent immigration to a country whose present opportunity is built on previous, forced Black labor. We will decline to say that this necessarily creates a debt, but one might see how Black individuals may walk into institutional situations feeling something to that effect. For our part, we have little patience for those who would benefit from this system and feel no impetus to make it more equitable and more just, even if that means taking a few extra steps to connect to a Black colleague and to make them feel a part. At the same time, our very presence in academia is owed not just to Black labors, but to the work and fierce advocacy of many who look nothing like us. If a debt is owed, it is a reciprocal one. How to completely resolve the issue of inclusiveness is a subject for another paper and another day, when we have done the necessary study and contemplation to offer answers more confidently. What is clear is that the oft-recommended – but seldom done – resolution of open and honest communication rooted in a relationship of care and trust must be a first step. The second must be open and honest connection rooted in that same type of relationship. And a third must be partnership and collective effort, again, in the context of care and trust. If autoethnography has done nothing more than to help us demonstrate the effectiveness of this path, it has been a worthy endeavor and a worthwhile contribution to science.

A Community-Based Response to Charlottesville

The following piece was originally featured by The Hill on 8/16/17 under the title “Trump’s actions are more telling than his words on Charlottesville.” Heath Brown is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at John Jay and an opinion contributor to The Hill.

There’s been a lot of attention paid to what President Trump has or has not said about the white nationalist march in Charlottesville, VA. Commentators are right to point to the weak statements from the President and White House as it demonstrates an unwillingness to use one of the most important powers of the presidency to confront organized racism, anti-semitism, and violent bigotry.

But a president’s powers don’t end at moral suasion and rhetoric. The President oversees a massive federal bureaucracy that has historically confronted civil rights violations and violent extremism. Just six months into his administration, the President has also failed to use this power to address the rise of the anti-African American, anti-Muslim, and anti-immigrant crime.

For example, in his initial budget for the Department of Homeland Security, the President cancelled grants to several community organizations focused on fighting hate, preferring to focus on the threat posed by ISIS. This is unfortunate because grants to groups like, Life after Hate, can leverage the numerous ways local organizations address intractable social problems, and for very little money.

This missed opportunity also signals a way forward on difficult racial and ethnic issues facing the country. Community groups already provide so many services to those in need, from education to job training to healthcare. These groups can also provide a voice for those victims of hatred and represent community concerns with public officials.

This is especially important during election time when we decide who will make important decisions about government spending. I’ve found that for organizations serving immigrants, less than half have participated during recent elections. That means too few organizations are helping to register new voters, inform residents about important campaign issues, or mobilize communities on Election Day.

This is another missed opportunity to confront white nationalism and hatred, especially when we consider how effective community-based organizations can be in responding to a rise in racial violence like we’ve seen since last fall. During the 2012 election, organizations such as the Sikh Coalition quickly responded to the murder of Sikh worshippers in Oak Creek, Wisconsin. These groups successfully urged the Department of Justice to classify the murder as a hate crime and commit federal resources to the case.

Elsewhere in the country, even though there is a small percentage of immigrant organizations participating in elections, for those that do, they make a major difference. Since it began registering voters in 2004, the MinKwon Center for Community Action has registered 70,000 new voters in New York City. Similar organizations door-knock and phone-bank in numerous languages to make certain every eligible voter knows where and when to vote.

Various forms of racism are embedded in American society and institutions. A thorough response must be just as comprehensive, reliant on the work of office holders, officials in government, and community groups working together with the citizenry. For community groups to play this role they must be supported, not just from federal grants, but also through state and local sources, philanthropy, and neighborhoods that encourage this type of participation.

The Diffusion of Victim’s Rights in Latin America: Notes on Ongoing Research

The following piece gives notes for the ongoing research by Dr. Veronica Michel, an Assistant Professor of Political Science. This research evaluates criminal procedure cross-nationally to examine victim’s rights in Latin America. It was originally posted in 2017.

For almost a decade I have been doing research on victims’ rights in Latin America. My interest in this topic began because while conducting research for my dissertation at the University of Minnesota I learned that victims of crime in most Latin American countries are granted a very interesting procedural right: the right to private prosecution within criminal proceedings.

I have explained in some of my previous publications (for instance, in this co-authored article with Kathryn Sikkink), that the right to private prosecution goes well beyond a victim’s right to speak granted in the US because the right to private prosecution grants the victim the right to participate with a lawyer in the prosecution of a crime. As interesting and important as private prosecution is for access to justice (and it is, as I argue here, here, and also in a forthcoming book), in Latin America victims of crime are granted many other rights. For instance, victims have strong reparation rights, like the right to introduce a civil claim within a criminal proceeding, also known as a civil action; and victims are also granted important protection rights, like the right to be informed about the state of the proceedings or the right to be offered shelter or protection when needed.

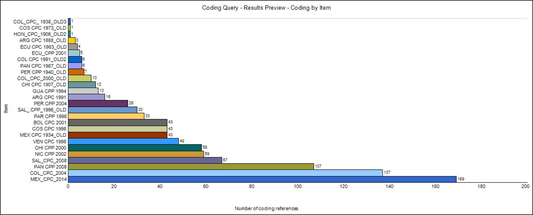

A content analysis of the current criminal procedure codes in 17 civil law countries in the region shows that these statutes provide quite a vast array of rights to victims of crime. What I find fascinating, however, is that all these rights are quite new. Yes, victims have always existed as long as crime has been around. But “victims’ rights” as such are quite new. As you can see in the Word Cloud above, an analysis of these 17 current criminal procedure codes reveals that among the most used concepts in these statutes we find the words “victim” (víctima) or private prosecutor (querellante).

Moreover, a closer comparison of old and current criminal procedure codes also reveals that the more recent a statute is, the more references to “victims” it makes. Some old criminal procedure codes did not even include the word victim in the whole statute. For instance, the criminal procedure codes of Nicaragua of 1879 or even the one of Honduras from 1985, did not even once mentioned the word victim.

In contrast, since 1994 we have witnessed an expansion of victims’ rights in criminal procedure. For example, Mexico’s previous criminal procedure code of 1934 only mentioned the word victim twice. In sharp contrast, its latest statute which entered into force in 2014, mentions the word 169 times!

So where do these “victims’ rights” come from? Why is it that countries gradually embraced the “victim” and began to expand the rights granted to this actor? Why is it that most countries in the region today provide all these similar rights? These are the questions that I am now exploring in an article that aims to explain how Latin America came to have such a vast array of rights for victims. So, stay tuned. I will report soon a summary of my findings in this blog.

Recent Comments