Home » Uncategorized

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Honoring the Legacy of Dr. Maureen Allwood

John Jay College staff in the Office for the Advancement of Research join the college community in mourning the passing of Dr. Maureen Allwood, a distinguished researcher, educator, advocate, and friend. Dr. Allwood’s sudden departure on Monday, March 4, in Providence, Rhode Island, has left a profound void in the hearts of those who knew her. Yet, her legacy of warmth, inspiration, and tireless dedication to marginalized communities will endure for generations.

A valued scholar in the field of psychology, Dr. Allwood’s work focused on understanding the developmental effects of trauma and violence, particularly emphasizing their disproportionate impacts on different sociodemographic groups. At John Jay College, she was a beacon of academic excellence and served as a professor of psychology since 2007. She also co-directed the department’s mentorship program for underrepresented and first-generation undergraduate students, leaving an indelible mark on the community with her passion and expertise. Her commitment to fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion within academia was unwavering, and her impact extended far beyond the classroom.

While grieving, her profound impact on the John Jay College community resonates deeply. Reflecting on her legacy, Dr. Angela Crossman, the Interim Dean of Faculty and Professor in the Department of Psychology where Dr. Allwood worked, aptly captured the sentiments of many, stating:

“Dr. Allwood’s passing was an incredible shock that is still difficult to fathom and is a tremendous loss to us all. She was a brilliant scholar, a passionate mentor and teacher, a dedicated and thoughtful colleague, and a warm and kind friend. I admired her greatly, appreciated the important work she was doing on the impact of trauma and violence exposure on youth development, and was always incredibly grateful that she chose to make John Jay her academic home. The world is a better place for her having been a part of it, and she will be deeply missed by her friends, family, colleagues, and students – students who will carry on her legacy of impactful and important scholarship conducted with integrity, rigor, and care.” said Dr. Crossman.

Beyond her scholarly pursuits, Dr. Allwood’s impact was deeply personal, touching the lives of students, colleagues, and friends alike. Professor Daryl Wout, Chair of the Psychology Department and Associate Professor of Psychology, emphasized her brilliance and passion to spearhead efforts to cultivate a more inclusive environment within our College and at the CUNY university level.

“Dr. Allwood was a beloved member of the John Jay community. She was an active department member and contributed to our students’ development and our clinical program’s growth. She fiercely advocated for an increased focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and spearheaded various DEI efforts at the college and university levels. Her research on the developmental effects of trauma and violence and their disproportionate impacts on different sociodemographic groups has significantly impacted our understanding of this important area. As a mentor, she was extremely supportive and nurturing of her students. She always prioritized her students and their success, even while on sabbatical. Beyond her impact at the College, she was a loyal friend, an exceptional mother, and a committed wife. As a community, we have been blessed by her presence and are deeply mourning her sudden death. She will forever be in our hearts and minds.” said Daryl Wout.

Reflecting on Dr. Allwood’s profound influence, Distinguished Professor Kevin Nadal wrote in his Instagram post, “She was a no-nonsense educator and mentor—someone who wanted her students to succeed while always encouraging them to work their hardest and never make excuses. She was an extraordinary colleague—one of the few humans who made an oppressive place like academia feel welcoming. SHE is what a professor looks like.”

Dr. Maureen Allwood received the 2023 OAR Scholarly Excellence Award winner, exemplifying a commitment to excellence, and has won several accolades and grants for the College. Her most recent groundbreaking study, “Youth Exposure to Gun, Knife, and Physical Assaults,” which examined PTSD symptoms across various demographic groups, was notably featured in Impact Magazine 2023 of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Her legacy, as showcased in Impact Magazine, serves as a testament to her enduring influence in shaping our understanding of critical societal issues.

As we honor Dr. Maureen Allwood’s memory, let us carry forward her excellence, compassion, and advocacy legacy. Though she may no longer be with us, her spirit will continue to inspire us to strive for a more just and equitable world.

Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues 2020-23

The Office for Academic Affairs through its Office for the Advancement of Research, in collaboration with Undergraduate Studies and a faculty leadership committee representing Africana Studies (Jessica Gordon-Nembhard), Latinx Studies (José Luis Morín), and SEEK (Monika Son), sponsored a year-long community dialogue on racial justice research and scholarship across the disciplines. John Jay College faculty, students, and the broader community were invited to join four panel discussions and four hands-on workshops that invited a more in-depth discussion about changing the ways we teach and learn – specifically, by facilitating meaningful engagement with scholarship by and about people of color, and promoting the incorporation of research on structural inequities into curriculum college-wide. Over the course of the 2020-2021 academic year, events covered multi-dimensional topics including:

- racial disparities in health and mental health and trauma-informed pedagogy;

- the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative;

- economic inequality; and

- racism and discrimination in the criminal legal system.

Each panel was facilitated by a John Jay faculty member who also led a follow-up workshop intended to engage participants more deeply in the subject matter and promote best practices for cultivating racial justice in our classrooms and around the college. Each panel was recorded, and the recordings can be found below, as well as resource guides for further self-guided learning and curricular reform.

Series events, recordings and resources

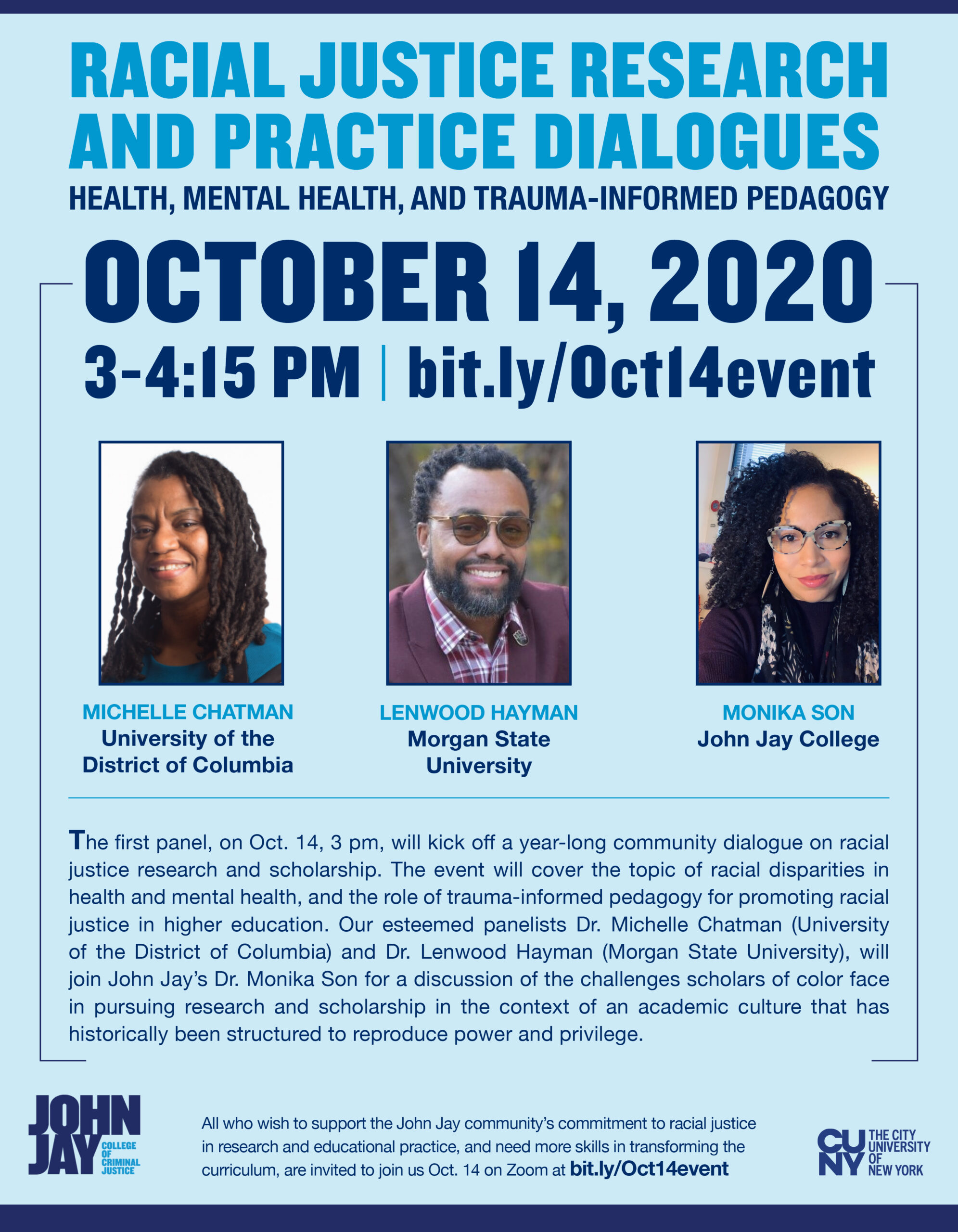

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Panelists: Dr. Michelle Chatman (UDC) & Dr. Lenwood Hayman (Morgan State University)

Facilitator: Dr. Monika Son (JJC)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/NYTxARHOALw

Resources:

- Ayers, W., Ladson-Billings, G., & Michie, G. (2008). City kids, city schools: More reports from the front row. The New Press. Introduction, pgs 3-7.

- Chatman, MC. (2019). Advancing Black Youth Justice and Healing through Contemplative Practices and African Spiritual Wisdom. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 6(1):27-46.

- Monzó, L. D., & SooHoo, S. (2014). Translating the academy: Learning the racialized languages of academia. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(3), 147–165. DOI: 10.1037/a0037400

- Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Arch of Self, LLC, https://www.yolandasealeyruiz.com/archaeology-of-self

For additional suggested readings, prompts for discussion, and curricular resources, download our full event guide: RJD Event 1.1 Homework and Readings.

Event #2: Race and Historical Narrative — Correcting the Erasure of People of Color

The second panel in the OAR/UGS Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues series, on November 11 at 3 pm, will shine a light on the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative commonly taught in the United States. This erasure is harmful to students of color in particular, as they do not see themselves represented in the stories told about this country, and actively harms people of all races by failing to present an accurate picture of the country’s founding and history.

Panelists: Dr. Paul Ortiz (UFL) & Dr. Suzanne Oboler (John Jay College)

Facilitator: Dr. Edward Paulino (John Jay College)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/WRIDHIA_a94

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the RJD Event 2.1 – Readings.

Event #3: Economic Inequality and Wealth Disparities

Panel Discussion – March 24, 2021, 4:30 – 5:45 pm

Panelists: Dr. Naomi Zewde (CUNY SPH) & Dr. Stephan Lefebvre (Bucknell University)

Facilitator: Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard (JJC)

Event Recording: https://youtu.be/_lp93i3EHqE

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Economic Inequalities – Resources.

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Panel Discussion – April 21, 2021, 3 – 4:15 pm

Panelists: Dr. Jasmine Syedullah (Vassar College) & Professor César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández (University of Denver, Sturm College of Law)

Facilitator: Professor José Luis Morín (JJC)

Recording: https://youtu.be/OZ8N-c7Gob0

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Resources – Racism in the Criminal Legal System

The series continued in academic year 2021-2022, expanding the scope of the discussions with panels on racial equity in disaster recovery.

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

The fifth panel took place on November 1, 2021, and addressed the interdependent roles of government agencies, community-based and non-governmental organizations in promoting or hindering equitable outcomes in post-disaster situations. Panelists included Kim Burgo (Catholic Charities), Craig Fugate (One Concern), Dr. Jason Rivera (Buffalo State College), Dr. Warren Eller (John Jay College), and Dr. Dara Byrne (John Jay College). Find the recording at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQkjxw6RcKg.

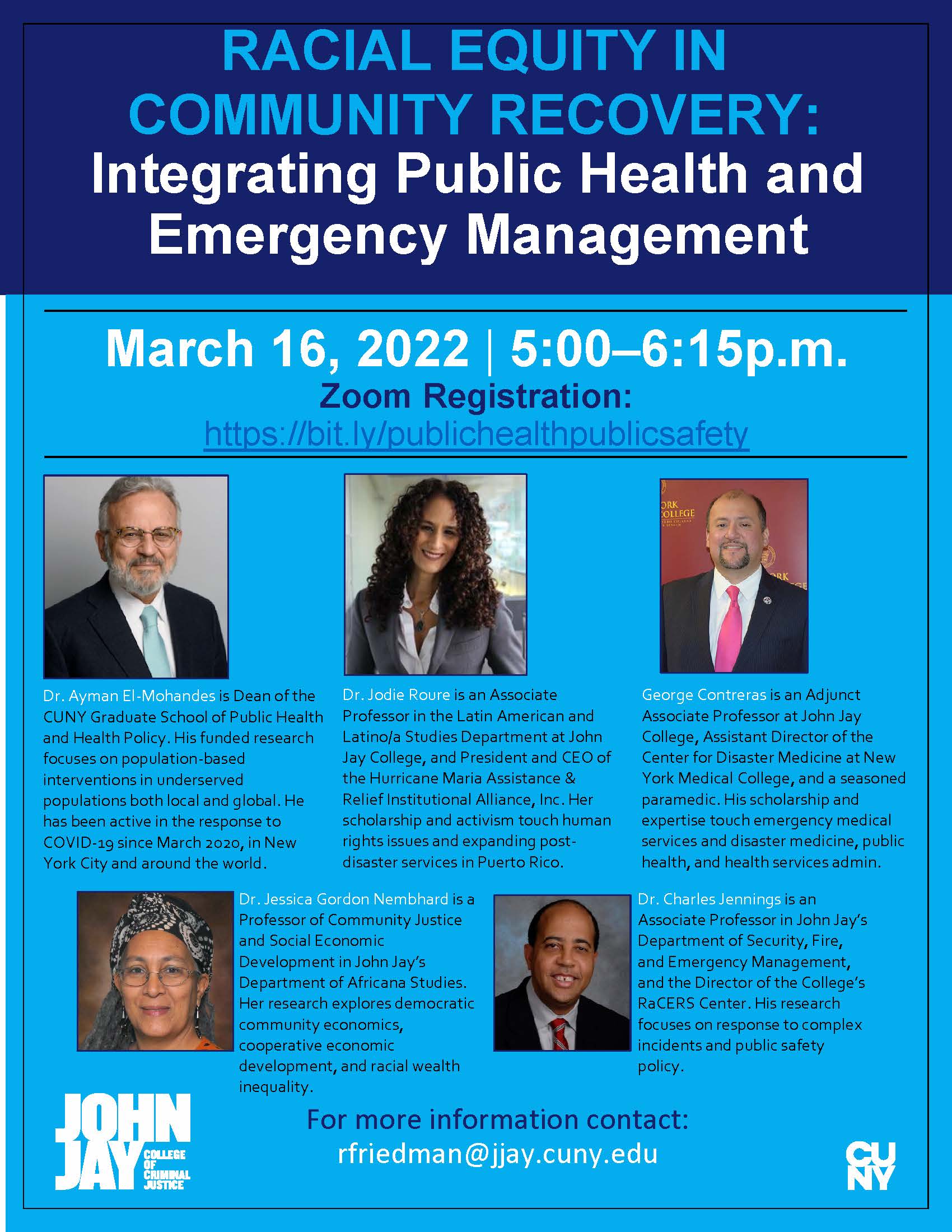

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

The sixth panel in the series, which took place on March 16, 2022, continued the theme of racial equity in disaster recovery. Panelists explored the overlapping roles of the institutions of public health and public safety in promoting equitable outcomes in post-disaster recovery, addressing the intersectional challenges faced by people of color and other marginalized communities. The conversation took special note of the particular context of post-COVID recovery. The participants were Dr. Ayman El-Mohandes (CUNY Graduate School of Public Health), Dr. Jodie Roure (John Jay College), and George Contreras (New York Medical College, John Jay College). The moderators were Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard and Dr. Charles Jennings (John Jay College). A full recording of the event is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4u9wUyjr5Sg&list=PL-B85PTQbdJj5UJhqiddjs1_9p90pZXTZ&index=6.

Resources:

- , 2020: COVID-19: A Barometer for Social Justice in New York City, American Journal of Public Health

- El-Mohandes, A., White, T.M., Wyka, K. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adults in four major US metropolitan areas and nationwide. Sci Rep

- Roure, Jodie G. The Reemergence of Barriers During Crises and Natural Disasters: Gender-Based Violence Spikes Among Women and LGBTQ+ Persons During Confinement. Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, pp 23-50, 2020.

- Jodie G. Roure, 2020 presentation: Children of Puerto Rico & COVID-19: At the Crossroads of Poverty & Disaster.

- Jodie G. Roure, Immigrant Women, Domestic Violence, and Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico: Compounding the Violence for the Most Vulnerable. The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 2019.

- Contreras GW, Burcescu B, Dang T, et al. Drawing parallels among past public health crises and COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.202.

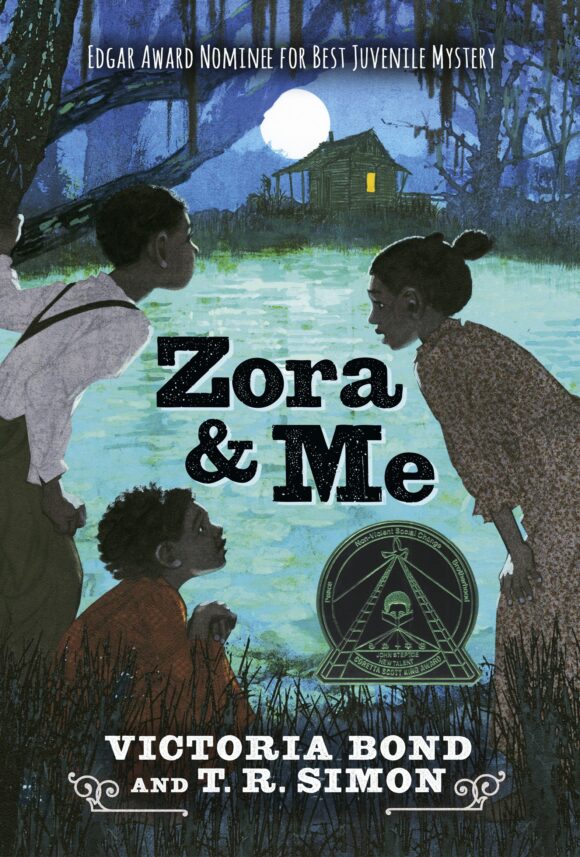

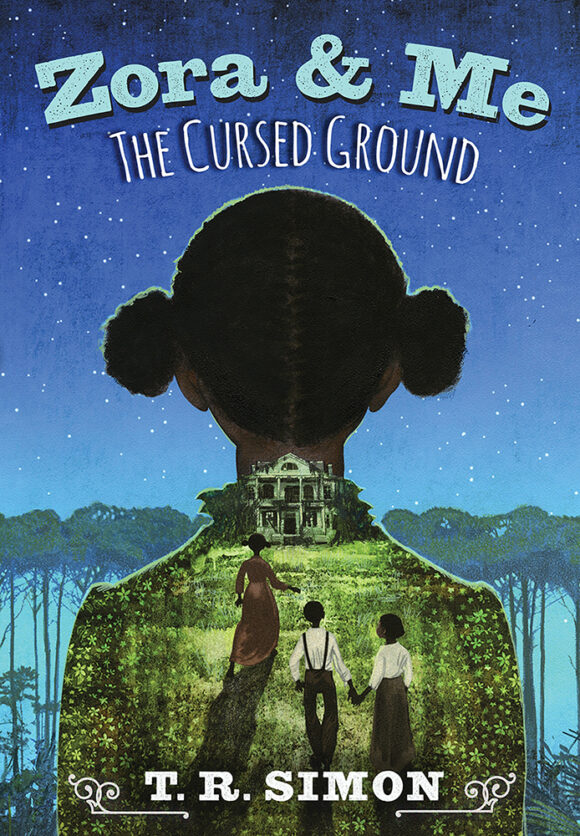

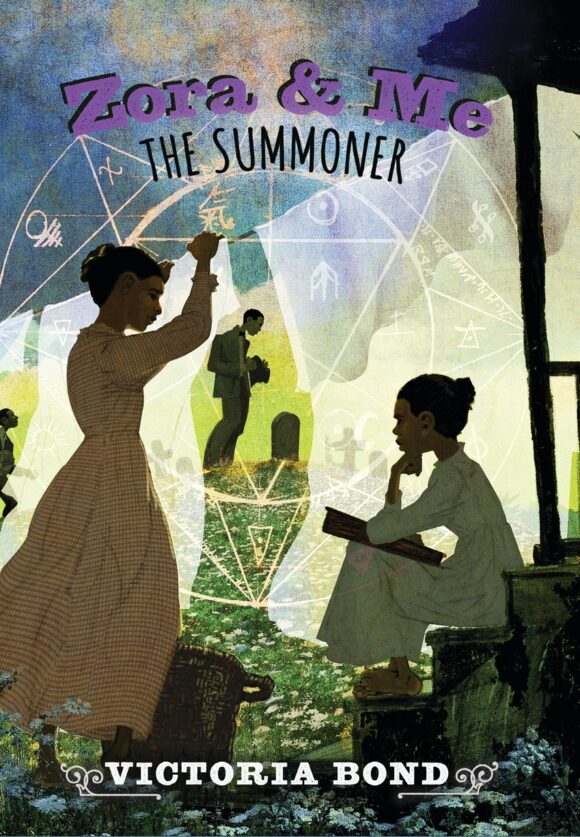

Victoria Bond’s ‘Zora and Me’ Trilogy Closes With ‘The Summoner’

Victoria Bond is a lecturer in John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s English Department, and the co-author with T. R. Simon of a series of young adult novels inspired by the childhood of American literary icon Zora Neale Hurston. The Zora and Me trilogy fictionalizes a young Zora as what The New York Times calls a “girl detective,” living in Hurston’s real-life hometown of Eatonville, Florida. Through the use of tropes from mystery and horror, the books explore community, and the fragility of justice for Black people.

In the first novel, Zora and Me, stories about a shape-shifter lead Zora and her best friend Carrie (the narrator) to solve a murder mystery. The second novel of the series, The Cursed Ground, sees Carrie and Zora learning more about the dark, unforgiveable history of slavery from a ghost. And in Bond’s latest and final novel, Zora and Me: The Summoner, Eatonville experiences upheaval that causes Zora’s family to seek their fortunes elsewhere. The use of zombies in this book, Bond says, is a way to explore the exploitation and trauma of African American lives.

Each installment of the trilogy may incorporate dark, scary elements, but, according to Kirkus Reviews, the brilliance of the novels is that they are able to render African American children’s lives during the Jim Crow era as “a time of wonder and imagination, while also attending to their harsh realities.”

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Alabama in 1891 and published several novels and many short stories, plays and essays, although she is best known for her classic Harlem Renaissance novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Zora and Me was the first novel not written by Hurston herself that has been endorsed by the Zora Neale Hurston Trust, founded in 2002. To bring the real Zora’s experiences in her hometown of Eatonville, Florida, to life, Bond and Simon researched Hurston’s life extensively by reading her biographies and her 1942 autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road. They sought to create a story right for young adult readers that was true to the historical period in which it takes place, and which features a smart, spirited Black girl with a vivid imagination, ready to inspire other girls.

Zora and Me: The Summoner is forthcoming from Candlewick Press on October 13, 2020, and available for preorder now. To learn more about Zora Neale Hurston from author Vicky Bond, watch her in this short video on YouTube. Or to learn more about the experience of writing a novel during these uniquely difficult times, read this post from the author.

Dr. Phillip Atiba Goff – Data Science for Justice

On April 16, 2019, John Jay College’s Franklin A. Thomas Professor in Policing Equity Dr. Phillip Atiba Goff spoke at Session 4 of TED2019 in Vancouver. The program featured eight speakers representing eight projects that are receiving funding from The Audacious Project in 2019. Dr. Goff spoke on behalf of his independent non-profit organization, the Center for Policing Equity (CPE), which was one of this year’s Audacious Projects.

CPE focuses on addressing racism in the United States. According to Dr. Goff, “When we change the definition of racism from attitudes to behaviors, we transform that problem from impossible to solvable.” CPE’s project, COMPSTAT for Justice, is a database leveraging data collected from police departments and cities on police behavior in an effort to identify problem areas where specific police behaviors can change.

With the support of The Audacious Project, CPE wants to extend the results it’s already seen with partners adopting COMPSTAT for Justice, by delivering the project to police departments serving 100 million people across the United States over the next five years.

To hear Dr. Goff’s TED Talk, visit the @TEDTalks Twitter page, where the link to the livestream is still up. You can read more about Session 4 of TED2019 on the TEDBlog.

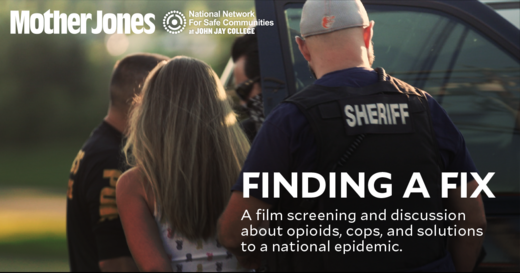

National Network for Safe Communities Hosts Film Screening, Panel on Opioid Crisis

By Raymond Legendre

Amidst the deadliest drug epidemic in American history, the National Network for Safe Communities (NNSC) hosted a documentary film screening and panel discussion on October 2 that highlighted why the opioid crisis is so difficult to stop, and shared the actions being taken in New York City to save lives.

The event featured the Mother Jones short documentary series, Finding a Fix, with a brief introduction by filmmaker Mark Helenowski, and a subsequent panel conversation including New York City council member Stephen Levin, Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Kaitrin Roberts, and community organizer Marilyn Reyes, co-chair of the Peer Network of New York. Mother Jones reporter Julia Lurie also participated on the panel, which was moderated by NNSC Director David Kennedy.

In 2017, drug overdoses claimed an estimated 72,000 lives in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of those deaths, more than 49,000 were attributed to opioids. New York City alone recorded around 1,500 overdose deaths last year. The current death rate is equal to one New Yorker dying from an overdose every six hours, according to ADA Roberts. The availability of Narcan, a nasal spray that can reverse opioid overdose, is often the different between fatal and non-fatal overdoses, the prosecutor also noted. In August 2017, New York became the first state to make no-cost or lower-cost medicine to reverse opioid overdoses available at pharmacies.

To learn more about the event, read the rest of this article on the NNSC website. To learn more about the work NNSC does, visit their homepage.

CUNY Graduate Center Hosts Press Briefing by Immigration Experts

August 8, 2018 – The Graduate Center of CUNY has the benefit of some of the best immigration scholars in the country. Ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, in which this contentious issue will play (and has already been seen to play) a big role, six distinguished faculty experts on immigration sat down to brief the press on a variety of issues surrounding evolving immigration policy under the Trump administration and related issues, including demographics, economics, and the sociocultural experience of immigrants in the United States.

The panel kicked off with CUNY Graduate Center Distinguished Professor of Sociology Richard Alba, who introduced the idea that immigration policy under President Trump is the most restrictionist and selective this country has seen since the inter-war period of the 1920s. However, he suggested that there are a number of structural constraints on this administration’s ability to push immigration restrictions too far. These include business’s need for new workers, both skilled and unskilled; demographic indicators of an impending dearth of young workers; and a lack of political will even among a Republic Congress to enact major immigration legislation.

Next, David Brotherton, a professor of sociology and criminologist from John Jay College, brought up the idea that the “deportation regime” under Donald Trump is not unique in the history of the United States. He noted earlier examples of deportation- or exclusion-oriented federal policy, including the 1996 Immigrant Responsibility Act, Indian Removal Act, and the 19th century Chinese Exclusion Act. Dr. Brotherton went on to discuss the origins of the Trump Administration’s restrictive immigration policies, particularly the president’s campaign tactics of stoking panic in a segment of the population that feels insecure about their place in society. He emphasized that this strategy represents only the latest in a series of moral panics in American history, calling back to the War on Drugs and earlier rhetoric about the dangers of young black and Latino men.

Dr. Brotherton described U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as arguably the “largest police force in the United States.” ICE’s detention and deportation of immigrants is retroactively punishing many non-native Americans for crimes in their pasts; because these individuals have since put down roots in the country, with families, jobs and wider communities that are hurt when they are suddenly taken away, the policy is cruel. For this reason, Dr. Brotherton has acted as an expert witness since 2007, testifying to the effects of deportation on the individuals detained, their communities, and even their representation.

A second immigration project that Dr. Brotherton is currently engaged in is “Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime,” in which he collaborates with Graduate Center faculty to treat New York City – a sanctuary city, and the only city that guarantees representation to immigrant detainees – as a case study. The project aims to look at this problem from all angles and account for many perspectives.

The next commentator was Margaret Chin, a professor of sociology at Hunter College, who focused on the problem of “glass and bamboo ceilings” that stand in the way of Asian-Americans’ achieving educational equity in New York City. She emphasized the importance of taking race into account when designing programs, such as student tracking and race-conscious admissions.

Nancy Foner, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, is the author of a number of books on immigration. During the briefing, she strove to correct immigration myths that are being spread by the president and members of his administration. First, that immigrants are criminals; in fact, immigrants commit less crime than native-born Americans (excepting immigration infractions), and cities and neighborhoods with higher concentrations of immigrant populations have lower rates of crime that comparable neighborhoods. Second, that today’s immigrant populations aren’t learning English; the “three-generation model” continues to be accurate in describing language-learning patterns in immigrant families. The United States can be called a “graveyard of languages” because immigrants tend to lose their native tongues in favor of English – typically by the third generation, individuals are mostly monolingual in English.

Debunking these myths, according to Dr. Foner, is important to reducing the hostility toward immigrants upon which the administration’s restrictive immigration agenda is predicated. She emphasized that social scientists and journalists alike have a responsibility to help publicize the truth about immigrants and their contributions to society.

According to Philip Kasinitz, a Presidential Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, the underlying strategy of the Trump Administration on immigration is difficult to understand, in that much of the policy is self-contradicting. He noted several key contradictions around the thinking on immigration today. For example, the current moral panic conflating immigrants, illegality and crime comes at a time when crime rates – particularly violent crime – is way down. Americans are also increasingly supportive of immigrants and their participation in society, but increasingly make a distinction between legal and illegal, creating a class of people involved socially, economically and culturally in our society but not politically, a fact that is, in his view, bad for a democratic society. Finally, Dr. Kasinitz talked about the generational factors behind a society that is increasingly diverse, but which at the same time harbors extreme anti-immigrant sentiments.

John Mollenkopf, Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Sociology, also noted contradictions inherent to the views of an older, white segment of the population: their anxiety about allowing immigrants into the country is not in their economic best interests, as many are increasingly dependent on low-wage immigrant labor for their care. As a scholar of the acquisition and use of political power, Dr. Mollenkopf opined that the best way to limit the ability of Republicans in Congress to build a base around anti-immigrant sentiment is to mobilize the increasing numbers of immigrant-origin voters and bring new constituencies into the electorate. In New York City, for example, the majority of the electorate is of immigrant origin, but newer immigrants have not yet organized to develop the same amount of political influence as groups that have been in the United States in large numbers for longer.

The panel wrapped up with questions from the audience. In particular, the discussion touched on the movement to abolish or reform U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an idea that has received some popular attention among Democrats in the lead up to the 2018 midterm elections. Dr. Brotherton said that “a critical mass of people has disappeared” in Latin American and Central American communities, and immigrants across the country have changed their routines out of fear of the agency. Dr. Kasinitz clarified that, despite popular belief, the number of deportations has not risen; rather, the length of immigrant detentions has grown substantially due to a lack of capacity in immigration courts to process detainees. All agreed that more dramatic action or a greater groundswell of support for reform is needed to signal that ICE’s actions are not acceptable to a majority of Americans.

For more information about the immigration research coming out of the CUNY Graduate Center, please visit the GC Immigration page.

Fostering Success in STEM – Dr. Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín

Dr. Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín sees himself in the PRISM students he works with. He credits his alma mater, the University of Puerto Rico, with instilling in him the spirit of preparedness that he brings to student researchers and presenters at John Jay — being ready not only with the technical facts but with the message about why your research is important, and how you are changing the world.

Dr. Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín sees himself in the PRISM students he works with. He credits his alma mater, the University of Puerto Rico, with instilling in him the spirit of preparedness that he brings to student researchers and presenters at John Jay — being ready not only with the technical facts but with the message about why your research is important, and how you are changing the world.

“Because of that, every time we go to a conference, we get minimum one award — my top is three!” he says. “Every time we go to an undergraduate research conference, John Jay’s name always comes up.” It is this tangible commitment to bringing out the best in John Jay’s science students that earned Dr. Sanabria-Valentín, who is the Associate Director of the John Jay Program for Research Initiatives in Science and Math (PRISM), a 2018 APACS President’s Award.

At its heart, PRISM is about teaching students skills, not only in the sciences but also to prepare them to succeed in and after college. “The bread and butter upon which PRISM was founded” is the Undergraduate Research Program. The program provides students with opportunities to be exposed to the process of science beyond their normal classroom studies by working directly with a faculty mentor on an original STEM research project.

And PRISM has grown. A second component is the Junior Scholars program, giving academic support to eligible students that can include stipends, professional development events and supplementary advisement, as well as financial support in applying to post-graduate programs in New York State-licensed professions. Just as important for an institution that counts many first-generation college students among its student body, Junior Scholars collaborates with student support services across the college, like the Math and Sciences Research Center, Center for Career and Professional Development, Wellness Center, Center for Postgraduate Opportunities, and even more. The program is designed to make sure that students have all the tools to get to know their college and excel.

External funding is part of what drives PRISM’s growth. The New York State Collegiate Science and Technology Entry Program, or CSTEP, awards grants to postsecondary and professional schools to start academic support programs — like PRISM — for students from underrepresented minority groups, or who are economically disadvantaged, to help them get into STEM fields. John Jay was among the first class of schools to receive CSTEP funding, thirty years ago and out of roughly 200 PRISM students, the CSTEP grant supports 140. Edgardo’s goal is to double that number over the next five years.

His hard work is a large part of why the CSTEP program is at John Jay — after a short hiatus, Edgardo’s application brought the program back in 2015 — and of John Jay’s unique status as the only school to have institutionalized this type of academic STEM-focused support initiative. He is also responsible for collaborating with other CSTEP schools in the region: NYU, Hostos Community College, Fordham, City College and Mt. Sinai are among the Manhattan and Bronx institutions that participate with John Jay in our CSTEP Regional Research Expos. Participating students are invited to present their own research in poster sessions and attend professional development activities.

His work on and logistical support for the expos has earned Edgardo an award from the President of the Association of Program Administrators for CSTEP and STEP (APACS). The honor also recognizes his success in running a program that benefits students in the sciences. The advisement services offered by PRISM have created the conditions for increased student success at John Jay and degree completion, and the program puts students on a path toward the pursuit of higher degrees, or toward a place in the workforce in a variety of science, technology and computer science fields. The Undergraduate Research Program has measurably helped students to pursue post-graduate degrees in science, medicine and more.

The bottom line for Edgardo, though, is his students. “My kids blow me away every time,” he gushes. “I have complete pride in showing them off at every conference I go to. I have learned so much by helping them with posters and advising on their projects; it’s encouraging that I sometimes find my students to be smarter than me.”

Learn more about:

PRISM: http://prismatjjay.org/

APACS: http://www.apacs.org/

CSTEP in New York State: http://www.highered.nysed.gov/kiap/colldev/CollegiateScienceandTechnologyEntryProgram.htm

Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín, Ph.D. is the Associate Program Director for PRISM and also the Pre-Health Careers Advisor at John Jay. He holds a Ph.D. from NYU-School of Medicine, where his dissertation work involved studying the mechanisms Helicobacter pylori employs to persist in the human stomach for the life span of each host. He came to John Jay after a Post-Doctoral Fellowship at Harvard Medical School followed by 3 years working in the Biotechnology Industry in Boston. Dr. Sanabria-Valentín is the recipient of the ESCMID Young Scientist Award (2007), a Leadership Alliance-Schering Plough Graduate Fellowship (2006), and the NBHS-Frank G. Brooks Award for Excellence in Student Research (2001). He is also a founding member of the NYC-Minority Graduate Student Network and The Leadership Alliance Alumni Association.

Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín, Ph.D. is the Associate Program Director for PRISM and also the Pre-Health Careers Advisor at John Jay. He holds a Ph.D. from NYU-School of Medicine, where his dissertation work involved studying the mechanisms Helicobacter pylori employs to persist in the human stomach for the life span of each host. He came to John Jay after a Post-Doctoral Fellowship at Harvard Medical School followed by 3 years working in the Biotechnology Industry in Boston. Dr. Sanabria-Valentín is the recipient of the ESCMID Young Scientist Award (2007), a Leadership Alliance-Schering Plough Graduate Fellowship (2006), and the NBHS-Frank G. Brooks Award for Excellence in Student Research (2001). He is also a founding member of the NYC-Minority Graduate Student Network and The Leadership Alliance Alumni Association.

John Jay Research Blog

The Office for the Advancement of Research, as part of our Public Scholarship Initiative, actively solicits blog entries from John Jay faculty, staff, and external scholars working on issues of key contemporary and historical significance. We promote these entries on social media, including Facebook and Twitter, as well as within the university through a partnership with our Marketing and Development Office. If you wish to contribute an entry, please contact Research Communications Specialist Remmy Bahati at rbahati@jjay.cuny.edu with a brief (1-2 sentence) summary of your proposed entry.

“Manufactured” Mismatch: Cultural Incongruence and Black Experience in the Academy

The following piece gives notes on the autoethnography by Criminal Justice PhD students Kwan-Lamar Blount-Hill and Victor St. John, which was the *winner* of the “Best Article Award” by the Awards Committee of the American Society of Criminology Divison on Critical Criminology and Social Justice. This piece voices their shared experience in traditionally non-minority institutions. Click here to view the full article, originally published January 23, 2017.

Autoethnography is still somewhat avant garde in the field of criminology and criminal justice. The notion of a researcher “studying” her or his personal experience and history engenders some skepticism as to a works’ objectivity and, therefore, its value. What this misunderstands is the realization that there is value in the subjective. We, as scientists, also prize objectivity as valuable, but our work has been premised on the idea that subjective perceptions matter. Kwan has focused his study on perceptions of government legitimacy, how the perception of injustice is enough to cultivate cynicism, encourage disobedience, and spark rebellion. Victor has concentrated on how inmate perceptions of architectural features impact their receptivity to treatment, from conscious decision-making to subconscious processes to biochemical reactions at the cellular level. Women and men much more accomplished than us have built long-lasting careers on similar arguments.

“Manufactured ‘Mismatch’” uses autoethnogaphy to explore perception and, in that regard, we believe achieved its goal. In it, we accurately captured our felt experience and argued that it represented a state of feeling that might very well be shared beyond us. Examining our subjective perceptions, we came to understand perceived “mismatch” between us and our environment through the lens of cultural incongruence, where two cultures differ such that coming together causes stress, strain or all-out clash. The two cultures we identified as being, in our cases, at least partially incongruent were “Black culture” and the “culture of criminology and criminal justice.” Exploring the coming together of these two is already made difficult by the paucity of Black academics in the field, specifically coming from majority non-minority institutions. Having no outside resources to assist, we concluded that in-depth study of this population would be impossible for us. It so happens that both of us belong to this demographic and, at any rate, do not our perceptions matter too?

Our hypothesis was that Black culture and the culture of academic criminology might clash on several points. First, we hypothesized that Blacks would see themselves more likely to criticize mainstream institutions than other academics in the field, causing some friction with institutionalists. We hypothesized that Blacks would likely feel more religious or faith-oriented than their colleagues, causing friction with those who espouse faith-free intellectualism. We hypothesized that Blacks would perceive the academy as a much more intimate space, clashing with those see it in the nature of a transactional workplace environment. Finally, we hypothesized that Blacks would feel more inclined to see themselves as members of a collective, rather than emphasize their individual success, of course, clashing with those who feel otherwise. We separately examined our own experiences and perceptions of them, using a combination of record review and recollection to determine whether our hypotheses were supported. We found that they were. Our final hypothesis was that these felt differences would cause cultural mismatch, and that cultural mismatch might be the cause of Black academic struggles, as opposed to the intellectual mismatch that has historically been offered as an explanation.

Autoethnography is valuable because it allows for deep dives into researcher perceptions that create the potential for avenues of further study and, hopefully, for further action. By no means would we argue that our study proves the existence of anything but our own personal feelings about our experience. What we would argue is that it supplies a worthy reason to engage in further study on the topic. This is particularly the case for those who profess to have genuine concern in mitigating these tensions by creating spaces where friction is not quite so palpable or by creating systems that can guide Black students, and others, through it.

Again, autoethnography creates the potential for avenues of further study and further action, though we did not anticipate the many ways it would. One such way was by revealing and explaining our feelings about our experience to colleagues who had not understood them. By writing our thoughts on the page, in the tempered language of scholarship, and allowing other academics to engage with it outside of the tense environment of direct confrontation, we allowed others the time and space to digest our message. We opened the door for later discussions that needed to be had, but were not on track to happen otherwise. Most impactful, thus far, the work generated an invitation to meet privately with a colleague of ours to explore questions that had not been fully explained in our piece. The invitation was a courageous move on the part of a non-Black faculty member who was brave enough to wade into the waters of racial tension and to hold her own. She commended our work, yes, but also challenged us on the conclusions we drew from our perceptual experiences.

As scientists, we have a duty to forthrightly reexamine our interpretations when they are called into question. So, then, we want to take a moment to engage in some reexamination. Having done some of that, we have arrived at a number of additional conclusions. These are, again, based on our own perceptions and are in need of validation through further study. However, our description of incongruence appeared to emphasize how academic culture clashed with Black culture without adequately accounting for the position on the opposite side. We seek to address that here.

Taking our assumption of greater Black cynicism toward mainstream institutions into further consideration, we must admit that this might present a challenge even to those academic institutions that want to be more welcoming. This cultural phenomenon means that Black academics may often come into an institutional situation prepped for unfair treatment. The expectation is not unwarranted – we trust we need not go into the litany of ways that American societal institutions have engaged in discrimination and structural violence towards Blacks over the centuries. Black cynicism can be viewed as a protective adaptation of the culture, though one that leads to Black academics potentially misinterpreting personality disagreements as disagreements about race.

The situation is made more complicated in that some seemingly personal disagreements are actually about race, and our colleagues inability to see this when it happens only adds to our hypersensitivity around the subject and increases our interpretation through a racial lens. Moreover, in our colorblind society, racial tensions are often due to unintentional affronts. Non-Black colleagues will complain that their intentions were not malicious or ill, seeming somehow not to understand that, in the context of a societal arrangement which necessarily disadvantages Blacks, unintentional but ignorant attitudes and actions that perpetuate disadvantage and isolation are as harmful as intentional ones. That great misunderstanding only confirms Black skepticism of institutional environments and further racializes their interpretive lenses.

To further complicate matters, those non-Black colleagues who both understand the inherent challenge of Black success in mainstream institutions – success often coming from the backdrop of multi-generational, socio-structural disadvantage – and who want to be sensitive to those challenges may nonetheless find a mistake of theirs, or a personal disagreement, or a misunderstanding, suddenly characterized as a racial issue by their Black counterparts. When Black academics begin seeing professional interactions along racial – instead of interpersonal – lines, any one-on-one conflict can be transmuted into a battle of the races. Previous experience with racial discrimination or insensitivity reinforces the salience of a racialized perspective, which may then filter truly non-racial encounters through a racialized lens, further reinforcing its salience and possibly creating racial conflict from an interaction where none was originally intended – a cycle manufacturing mismatch.

Other aspects of Black culture beyond cynicism may also drive this. Black collectivism is a prime feature of the culture. For a people who have been oppressed en masse, individual experiences may become so similar that victory and tragedy are seen as shared. We can attest to this. As each other’s only Black male contacts in our doctoral program and then connecting on a shared perception of loneliness, we are now both intimately invested in our collective success. We see a challenge to one as a challenge to both. When Kwan perceives a problem of his as due to his race, we are both mobilized to respond. If Victor encounters a problem, racial or not, to the degree that it may stymie his success, it is still a challenge to us both. Our collective is not made up of just us. More than most of our colleagues, we are sure, our families are dependent on our success, not merely as a point of pride, but as a necessary step toward the family’s unitary economic and social stability. Still more, each time we walk into a classroom, we not only feel the responsibility of a professor to his students, but a responsibility to every Black face in the classroom to demonstrate Black potential and, to every non-Black face, the responsibility of demonstrating Black capability. We feel that we are not just ourselves, we are us all.

That weight may be, in some estimations, unwieldy, unwise and unjustified, but, to us, it is also undeniable and unavoidable. We feel personally proud of Black achievement and disappointed at Black failure because we are not spectators, but that achievement or failure is our own. And for those who point out the problems with such an approach, we retort that it was not one entirely of our own creation. American has consistently dealt with Blacks as if we were one writhing monolith. A rebellion on one plantation elicited punishment within several. Resistance to Jim Crow in one place sparked retaliation in several others. A policeman’s bad experience with one Black person leads to his rough treatment of others. Academics themselves have been guilty of conflating individuals into singularity – our paper explored how perceptions of historical religious ignorance and bigotry have made Black religiosity a mark of unsophistication and anti-intellectualism. Forced into one collective Black box, we cannot be blamed for responding in kind, as we are, for ill or good, all connected. Perhaps unfortunately, this may mean that a sensation misinterpreted as pain in one corner of the Black communal body often reverberates throughout, multiplying its intensity and the nature of the response.

Black cynicism and the adoption of vicarious experience as our own is a recipe for perceiving racial incivility in every corner. Interestingly, the professor we had the opportunity to speak with challenged one of our responses to perceived incongruence. She noted that we had developed a pattern of avoiding the institution due to our discomfort. Upon reflection, we must admit that truth. To paraphrase her point, our abandonment relinquished our claim to a place where we, in fact, belonged and our absence made it difficult for those who actually cared to determine how best to make that space more inclusive. Standing up to decry the isolation that drove us away might be seen as courageous, but fleeing the scene to complain from the outskirts was decidedly not. For this, we must take responsibility.

We would add, though, that many of our colleagues – even those who are well-meaning – have often taken a similar approach, avoiding depth of contact with us in order not to risk unwittingly hitting some racial landmine. Unwillingness to traverse into uncomfortable territory is not tenable for us, but equally untenable for non-Black others. Both harm the prospects for our field’s advancement beyond the “problem of the color-line.” We commit to doing our part in bridging the gap by seeking not to bring distrust where it is not deserved, by discerning the personal from the racial (inasmuch as these can be separated), and by being present. But we must demand, then, that others be willing to acknowledge the realities that breed distrust, and commit to being proactive and helping us to overcome not only our perceptual biases, but, more importantly, the oppressive structures that produce them

One way to do that is to take advantage of another aspect of Black culture that we explored – the search for personal connection. This will make many of our colleagues uncomfortable we are sure. However, when any academic stops to think how much of her or his own success is due to friendships and social ties with others, one must see that personal connection in the profession is not so foreign a concept. We merely suggest that, for those who care, the extra step to achieve closer bonds with Black counterparts on their terms may bring outsized dividends. We have a ready example: At the outset of writing this post, our thought was simply to amplify the message of our original piece. After a conversation with the professor, who we both felt truly cared about us – even if we do not always agree with her counsel – was able to change the tenor of this discussion.

There is no single person in the United States that has not benefitted from the contribution of Black American people, even if only indirectly through recent immigration to a country whose present opportunity is built on previous, forced Black labor. We will decline to say that this necessarily creates a debt, but one might see how Black individuals may walk into institutional situations feeling something to that effect. For our part, we have little patience for those who would benefit from this system and feel no impetus to make it more equitable and more just, even if that means taking a few extra steps to connect to a Black colleague and to make them feel a part. At the same time, our very presence in academia is owed not just to Black labors, but to the work and fierce advocacy of many who look nothing like us. If a debt is owed, it is a reciprocal one. How to completely resolve the issue of inclusiveness is a subject for another paper and another day, when we have done the necessary study and contemplation to offer answers more confidently. What is clear is that the oft-recommended – but seldom done – resolution of open and honest communication rooted in a relationship of care and trust must be a first step. The second must be open and honest connection rooted in that same type of relationship. And a third must be partnership and collective effort, again, in the context of care and trust. If autoethnography has done nothing more than to help us demonstrate the effectiveness of this path, it has been a worthy endeavor and a worthwhile contribution to science.

A Community-Based Response to Charlottesville

The following piece was originally featured by The Hill on 8/16/17 under the title “Trump’s actions are more telling than his words on Charlottesville.” Heath Brown is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at John Jay and an opinion contributor to The Hill.

There’s been a lot of attention paid to what President Trump has or has not said about the white nationalist march in Charlottesville, VA. Commentators are right to point to the weak statements from the President and White House as it demonstrates an unwillingness to use one of the most important powers of the presidency to confront organized racism, anti-semitism, and violent bigotry.

But a president’s powers don’t end at moral suasion and rhetoric. The President oversees a massive federal bureaucracy that has historically confronted civil rights violations and violent extremism. Just six months into his administration, the President has also failed to use this power to address the rise of the anti-African American, anti-Muslim, and anti-immigrant crime.

For example, in his initial budget for the Department of Homeland Security, the President cancelled grants to several community organizations focused on fighting hate, preferring to focus on the threat posed by ISIS. This is unfortunate because grants to groups like, Life after Hate, can leverage the numerous ways local organizations address intractable social problems, and for very little money.

This missed opportunity also signals a way forward on difficult racial and ethnic issues facing the country. Community groups already provide so many services to those in need, from education to job training to healthcare. These groups can also provide a voice for those victims of hatred and represent community concerns with public officials.

This is especially important during election time when we decide who will make important decisions about government spending. I’ve found that for organizations serving immigrants, less than half have participated during recent elections. That means too few organizations are helping to register new voters, inform residents about important campaign issues, or mobilize communities on Election Day.

This is another missed opportunity to confront white nationalism and hatred, especially when we consider how effective community-based organizations can be in responding to a rise in racial violence like we’ve seen since last fall. During the 2012 election, organizations such as the Sikh Coalition quickly responded to the murder of Sikh worshippers in Oak Creek, Wisconsin. These groups successfully urged the Department of Justice to classify the murder as a hate crime and commit federal resources to the case.

Elsewhere in the country, even though there is a small percentage of immigrant organizations participating in elections, for those that do, they make a major difference. Since it began registering voters in 2004, the MinKwon Center for Community Action has registered 70,000 new voters in New York City. Similar organizations door-knock and phone-bank in numerous languages to make certain every eligible voter knows where and when to vote.

Various forms of racism are embedded in American society and institutions. A thorough response must be just as comprehensive, reliant on the work of office holders, officials in government, and community groups working together with the citizenry. For community groups to play this role they must be supported, not just from federal grants, but also through state and local sources, philanthropy, and neighborhoods that encourage this type of participation.

Recent Comments