Home » 2022

Yearly Archives: 2022

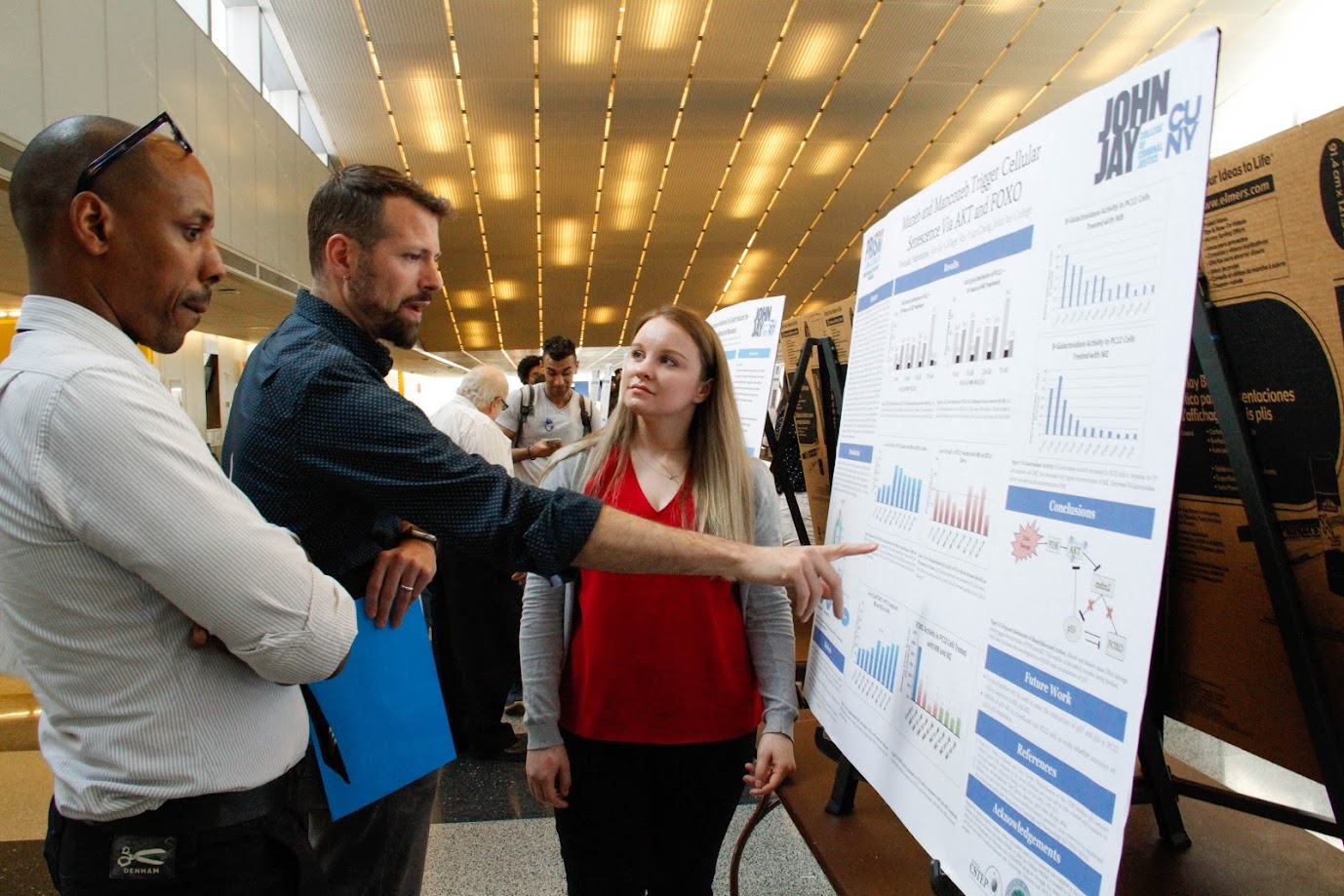

Back to the Lab with Dr. Jason Rauceo

John Jay College, along with CUNY schools across the city, are moving toward the resumption of on-campus life. Classes are attended in-person, events are being planned, and professors and students alike are headed back into the laboratory. I talked to one of John Jay’s professors in the Department of Sciences, Dr. Jason Rauceo, to find out what it’s been like closing down and reopening his lab.

Dr. Rauceo is an Associate Professor of Biology whose research focuses on the major fungal pathogen Candida albicans. He is also the Director of the Cell and Molecular Biology major at John Jay. In 2021, Dr. Rauceo received a four-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the role of the mitochondrion in C. albicans’ ability to infect hosts and cause disease.

What was it like to get back to lab work after a significant time away during the early part of the pandemic? Did you have to change any protocols or make adjustments to your operating procedures?

Right before CUNY closed in March 2020, I shut the lab down with the expectation that I would not return for 6-12 months. I returned to campus in September 2020, and the major challenge was reopening the lab myself. Students were not allowed on campus, and I needed to calibrate several instruments that I had limited experience operating. Fortunately, my students were available via Zoom and FaceTime for assistance.

What does a typical day in the lab look like, if there is such a thing?

The day usually begins with a short one-to-one meeting with whomever is scheduled to perform an experiment, in which we mainly discuss logistics. Throughout the day, I periodically check in to assist and address any experimental issues if needed. At the end of the day, I inspect the lab to make sure that workspaces are cleaned, all reagents and supplies are properly stored, and all students have left the lab.

What function do students play in your lab?

Students perform the hands-on experimentation and data analysis, and are responsible for general lab maintenance. They also contribute to the development of their projects, which must be directly related to the lab agenda—in this case, C. albicans biology. Students may propose their own experiments for approval after approximately 1.5 to 2 years of experience in the lab.

You place a lot of emphasis on experiential-based learning. What does that mean in practice for your students?

I allow students to test their own hypotheses when safety and costs are not an issue. Also, I allow students to make their own errors during initial training exercises. I found that this approach in lab research builds confidence.

Generally, in the early stages of a new project, a significant amount of time is devoted to optimizing protocols to meet our objectives. During this “optimization phase” of the research, there is an extensive level of troubleshooting required, and a high level of error and ambiguity is observed. I found that a major payoff of experiential-based learning and training is that students propose unique approaches to addressing experimental obstacles.

Your study of SPFH (Stomatin, Prohibitin, Flotillin, HflK/HflC) proteins’ role in mitochondrial function in Candida albicans is being funded by the NIH. It seems that there are some exciting implications for developing antifungal treatments—can you tell me about that?

SPFH proteins are widely conserved in nature and are found in most living organisms. These proteins are important for major biological processes including, but not limited to, respiration, transport, and communication. Candida albicans is a fungus that resides in all humans on mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and gastrointestinal tract in a harmless state. However, changes in our immunity sometimes cause C. albicans infections. Immunocompromised individuals are highly susceptible to C. albicans infections.

Currently, the function of SPFH proteins is limited in C. albicans. We were the first research group to demonstrate that SPFH proteins are required when C. albicans is challenged with environmental stress. Our current proposal seeks to define the molecular function of SPFH proteins. We are collaborating with several prominent research groups in fungal biology and medicinal chemistry to determine the function of the SPFH proteins in mitochondrial function.

One of our project aims is to understand the effects of treating C. albicans with natural compounds that target SPFH proteins. Our initial findings are promising and may be useful in developing novel antifungal strategies.

The NIH award provided me with the funds to expand my lab operations, and I’ve recruited three new undergraduate students; therefore, I will be spending much of the next semester in student training and performing experiments.

Sewage and the Science of Public Health – Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng and Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan Track Wastewater Contaminants

Wastewater is a topic that the average New Yorker doesn’t think about often, but perhaps we should. Sewage and run-off, over a billion gallons of which are treated every single day in New York City by 14 wastewater resource recovery facilities, are a valuable resource for scientists.

Wastewater sampling has been a useful tool for public health researchers tracking the COVID-19 pandemic over the last two years. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) launched the National Wastewater Surveillance System in September 2020 as a means of tracking virus spread and community prevalence. Viral genetic material is transmitted in fecal matter to the sewers and waste treatment plants, where researchers can take samples. Their work can serve as an early warning of community spread, track variants, and inform public health strategies for responding to the virus. Even better, wastewater surveillance doesn’t require individuals to seek out healthcare in order to capture information, meaning that the resulting data can include people who may be asymptomatic, who have taken home tests, or who have not been tested at all.

Wastewater data have figured prominently in several interesting COVID-19 stories recently in the news. In January 2022 the CDC reported that mutations associated with the Omicron variant showed up in New York City wastewater in November 2021, before the variant was officially reported in South Africa and at least a week before the first U.S. case was identified via clinical testing, suggesting that Omicron was likely circulating in communities before cases could be officially confirmed. And The New York Times recently reported on mysterious fragments of viral RNA with novel mutations detected in NYC wastewater, which are stumping researchers. They haven’t been able to pin down where these fragments are coming from, nor why these mutations have not shown up in clinical testing of human or animal populations in the city.

Two John Jay College researchers, Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng and Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan, are also big proponents of wastewater sampling studies as a public health tool. Their own research, published in 2019, tracked drug use over one year in New York City, using one-time grab samples to test for levels of cocaine, nicotine, cannabis, opioids, and amphetamines in the sewage. Now, the scientists are collaborating with non-profits that test the health of the city’s waterways, trying to correlate levels of pharmaceuticals in our rivers with the amount of harmful bacteria.

To Dr. Cheng and Dr. Concheiro-Guisan, wastewater analysis’s great strength lies in early warning and early intervention. “It’s a great tool for prediction, for public health, crime fighting, and disease [prevention] purposes,” says Dr. Cheng. “The official report is often too late, but if you can do an early intervention, find the issue and start addressing it, there’s a lot you can do.”

“We looked at wastewater because we saw the utility,” says Dr. Concheiro-Guisan. “This is a different application [than viral tracking] but with the same thought: that what we eliminate from our bodies tells you a lot about your population.”

However, the United States is late to the game. Though the CDC has had results with its national COVID-19 tracking program, both researchers lament the lack of a centralized American body to apply this research to other public health applications. They’d like to see the U.S. follow the example set in European countries, China, Australia, and increasingly in South America, where governments have applied wastewater sampling to create campaigns warning their citizens about novel psychoactives, catch drug manufacturers, and more.

“It’s a very important public health tool that is showing results,” says Dr. Concheiro-Guisan. “If you start in the biggest city in the country, if you start in New York, then others will follow.”

Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng is an Associate Professor and Chair of John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research is in the areas of toxicology and forensic pharmacology, including the roles that environmental toxins play in neurodegenerative diseases, identifying the target genes and signaling pathways affected by environmental toxins, and investigating pharmacological mechanisms of anti-cancer medications.

Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng is an Associate Professor and Chair of John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research is in the areas of toxicology and forensic pharmacology, including the roles that environmental toxins play in neurodegenerative diseases, identifying the target genes and signaling pathways affected by environmental toxins, and investigating pharmacological mechanisms of anti-cancer medications.

Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan is Assistant Professor of Forensic Toxicology in John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research focuses on the development and validation of analytical methods by gas and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and their application to different specimens, the detection of drug exposure during pregnancy, and the toxicological study of new psychoactive substances.

Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan is Assistant Professor of Forensic Toxicology in John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research focuses on the development and validation of analytical methods by gas and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and their application to different specimens, the detection of drug exposure during pregnancy, and the toxicological study of new psychoactive substances.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border.

Recent Comments