Home » Posts tagged 'City University of New York'

Tag Archives: City University of New York

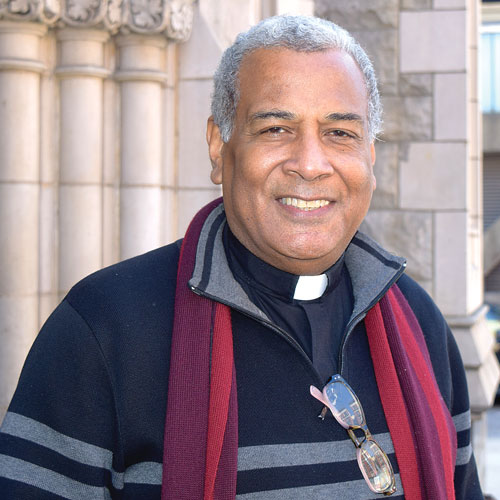

John Jay Institute Director Champions Education, Advocacy, and Policy Change for Black Empowerment

In celebration of Black History Month 2024, Andre Ward, the Executive Director of the John Jay Institute for Justice and Opportunity, reflects on a journey shaped by personal experiences within the criminal legal system. From incarceration to becoming the John Jay Research Center Director, his experiences drive a vision to empower formerly incarcerated individuals through education and to influence policy changes addressing social and racial inequalities. Read more about his background in the Q&A below.

As we celebrate Black History Month, can you share a bit about the journey that led you to John Jay’s Institute for Justice and Opportunity and a professional achievement that you believe has contributed to advancing justice and opportunity for the Black community?

I came to the institute as a result of my past involvement with College Initiative in 2009. I was released from incarceration on January 16, 2009 (the day Martin Luther King Jr’s birthday was observed), and two weeks later, I enrolled in Medgar Evers College. Earning both undergraduate and graduate degrees from CUNY’s Medgar Evers and Herbert H. Lehman Colleges, respectively, created opportunities for me to deepen my commitment to empowering the Black Community. After earning my Master’s Degree in Social Work, I was asked by the department chair at Medgar Evers College to return as an adjunct lecturer, where I taught mostly Black (and Latinx) students for 4 ½ years. Following this professional achievement, I localized myself in non-profit reentry/policy/advocacy work, culminating in a major New York City legislative win with the passage of the Fair Chance for Housing Act in December 2023. This legislation would prevent people with a conviction record from being discriminated against when applying for housing. For many justice-impacted college students like those whom we serve at the Institute for Justice and Opportunity, housing is indispensable to creating stability. This important legislation would protect them and the other 750,000 New Yorkers (80% of whom are Black and Latinx) from being denied access to housing solely on the basis of past justice system involvement.

How has your previous experience prepared you for the role of Research Center Director at the Institute for Justice and Opportunity?

Being directly impacted by the criminal legal system and working with diverse groups and students who had and did not have justice system involvement has prepared me for the role of Research Center Director at the Justice and Opportunity Institute. Additionally, my training as a social worker, policy/legislative change agent, and advocate for justice, fairness, and equity in education, employment, and housing – especially for people with conviction records – has also prepared me for this role. Serving in various capacities in New York City non-profit starting with providing job readiness/career coaching to facilitating academic and life skills workshops for students at Baruch College’s SEEK program and overseeing restorative justice/alternatives to incarceration work for young adults ages, serving as director of workforce development and executive leveled roles in advocacy and education and employment services, has prepared me for this role. My experience of being incarcerated has also served to prepare me for this role.

What is your vision for the Institute in promoting justice and opportunity, particularly within the context of Black communities?

My vision is to expand how we equip formerly incarcerated students with the knowledge and skills necessary for securing gainful employment, an essential factor often impeded by the stigma of a criminal record. Deepening existing stakeholder relationships while simultaneously innovating in areas of program service provision is part of my vision to move toward national and international education efforts.

Given the current social and racial inequalities landscape, how do you see the institute’s role in influencing policy changes that address these disparities?

The institute can support advocacy efforts that address discrimination in education. It can also join voting rights efforts to get our students involved in changing policy/legislation that impacts their lives. Through narrative sharing and engaging elected officials in the city and state, IJO’s students can become empowered to organize their communities to facilitate change. By doing so, members of the community become co-creators of public safety, thus creating the world they want to see and be in.

How do you see the institute actively contributing to the ongoing narrative of Black history and progress?

Education transcends the mere acquisition of knowledge; it serves as a catalyst for personal transformation. For formerly incarcerated individuals, this transformation can be profound. Education instills self-worth, purpose, and a vision for the future, offering a beacon of hope and a pathway to self-improvement. IJO will continue to serve as a place where justice-involved students can come. And through the impact IJO has on students, coupled with students developing an understanding of themselves, they will become assets to the community, creating a history of contribution that adds value to the black community and humanity.

IJO will actively nurture essential life skills, including critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making, which can be a powerful tool for psychological healing, helping individuals overcome the stigma and emotional burdens associated with their criminal history.

Western and Redburn (2017) emphasize in their seminal work, Education as Crime Prevention: The Case for Reinvesting in Prison Higher Education, that the role of education is to serve as a platform for self-improvement and a means for shifting individuals’ perspective from their past to their potential. This transformational aspect of education is pivotal in successfully reintegrating formerly incarcerated individuals into society, and IJO will maintain this work – especially during Black History Month.

How are you celebrating Black History Month?

I am celebrating Black History Month by actively making monetary and skills contributions to small Black organizations that support the communities we come from and focus on reentry and higher education services for people with a conviction record. I am also celebrating the amazing good fortune I have to serve our students alongside my deeply committed colleagues at IJO. Together, we are making a difference in the lives of Black people in particular, and humanity generally – one powerful academic student at a time.

Read more about the John Jay Institute for Justice and Opportunity here.

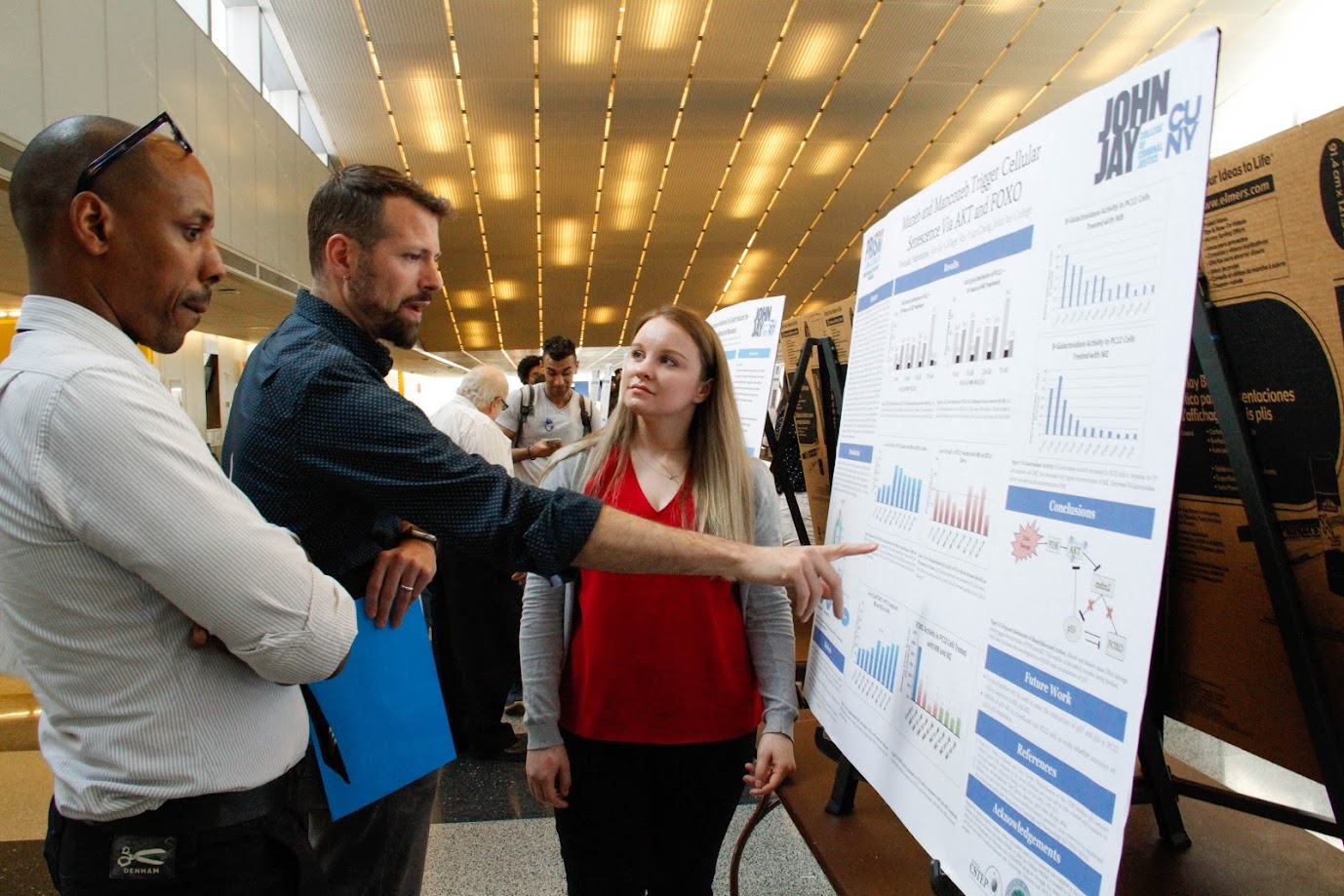

Back to the Lab with Dr. Jason Rauceo

John Jay College, along with CUNY schools across the city, are moving toward the resumption of on-campus life. Classes are attended in-person, events are being planned, and professors and students alike are headed back into the laboratory. I talked to one of John Jay’s professors in the Department of Sciences, Dr. Jason Rauceo, to find out what it’s been like closing down and reopening his lab.

Dr. Rauceo is an Associate Professor of Biology whose research focuses on the major fungal pathogen Candida albicans. He is also the Director of the Cell and Molecular Biology major at John Jay. In 2021, Dr. Rauceo received a four-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the role of the mitochondrion in C. albicans’ ability to infect hosts and cause disease.

What was it like to get back to lab work after a significant time away during the early part of the pandemic? Did you have to change any protocols or make adjustments to your operating procedures?

Right before CUNY closed in March 2020, I shut the lab down with the expectation that I would not return for 6-12 months. I returned to campus in September 2020, and the major challenge was reopening the lab myself. Students were not allowed on campus, and I needed to calibrate several instruments that I had limited experience operating. Fortunately, my students were available via Zoom and FaceTime for assistance.

What does a typical day in the lab look like, if there is such a thing?

The day usually begins with a short one-to-one meeting with whomever is scheduled to perform an experiment, in which we mainly discuss logistics. Throughout the day, I periodically check in to assist and address any experimental issues if needed. At the end of the day, I inspect the lab to make sure that workspaces are cleaned, all reagents and supplies are properly stored, and all students have left the lab.

What function do students play in your lab?

Students perform the hands-on experimentation and data analysis, and are responsible for general lab maintenance. They also contribute to the development of their projects, which must be directly related to the lab agenda—in this case, C. albicans biology. Students may propose their own experiments for approval after approximately 1.5 to 2 years of experience in the lab.

You place a lot of emphasis on experiential-based learning. What does that mean in practice for your students?

I allow students to test their own hypotheses when safety and costs are not an issue. Also, I allow students to make their own errors during initial training exercises. I found that this approach in lab research builds confidence.

Generally, in the early stages of a new project, a significant amount of time is devoted to optimizing protocols to meet our objectives. During this “optimization phase” of the research, there is an extensive level of troubleshooting required, and a high level of error and ambiguity is observed. I found that a major payoff of experiential-based learning and training is that students propose unique approaches to addressing experimental obstacles.

Your study of SPFH (Stomatin, Prohibitin, Flotillin, HflK/HflC) proteins’ role in mitochondrial function in Candida albicans is being funded by the NIH. It seems that there are some exciting implications for developing antifungal treatments—can you tell me about that?

SPFH proteins are widely conserved in nature and are found in most living organisms. These proteins are important for major biological processes including, but not limited to, respiration, transport, and communication. Candida albicans is a fungus that resides in all humans on mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and gastrointestinal tract in a harmless state. However, changes in our immunity sometimes cause C. albicans infections. Immunocompromised individuals are highly susceptible to C. albicans infections.

Currently, the function of SPFH proteins is limited in C. albicans. We were the first research group to demonstrate that SPFH proteins are required when C. albicans is challenged with environmental stress. Our current proposal seeks to define the molecular function of SPFH proteins. We are collaborating with several prominent research groups in fungal biology and medicinal chemistry to determine the function of the SPFH proteins in mitochondrial function.

One of our project aims is to understand the effects of treating C. albicans with natural compounds that target SPFH proteins. Our initial findings are promising and may be useful in developing novel antifungal strategies.

The NIH award provided me with the funds to expand my lab operations, and I’ve recruited three new undergraduate students; therefore, I will be spending much of the next semester in student training and performing experiments.

Sewage and the Science of Public Health – Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng and Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan Track Wastewater Contaminants

Wastewater is a topic that the average New Yorker doesn’t think about often, but perhaps we should. Sewage and run-off, over a billion gallons of which are treated every single day in New York City by 14 wastewater resource recovery facilities, are a valuable resource for scientists.

Wastewater sampling has been a useful tool for public health researchers tracking the COVID-19 pandemic over the last two years. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) launched the National Wastewater Surveillance System in September 2020 as a means of tracking virus spread and community prevalence. Viral genetic material is transmitted in fecal matter to the sewers and waste treatment plants, where researchers can take samples. Their work can serve as an early warning of community spread, track variants, and inform public health strategies for responding to the virus. Even better, wastewater surveillance doesn’t require individuals to seek out healthcare in order to capture information, meaning that the resulting data can include people who may be asymptomatic, who have taken home tests, or who have not been tested at all.

Wastewater data have figured prominently in several interesting COVID-19 stories recently in the news. In January 2022 the CDC reported that mutations associated with the Omicron variant showed up in New York City wastewater in November 2021, before the variant was officially reported in South Africa and at least a week before the first U.S. case was identified via clinical testing, suggesting that Omicron was likely circulating in communities before cases could be officially confirmed. And The New York Times recently reported on mysterious fragments of viral RNA with novel mutations detected in NYC wastewater, which are stumping researchers. They haven’t been able to pin down where these fragments are coming from, nor why these mutations have not shown up in clinical testing of human or animal populations in the city.

Two John Jay College researchers, Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng and Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan, are also big proponents of wastewater sampling studies as a public health tool. Their own research, published in 2019, tracked drug use over one year in New York City, using one-time grab samples to test for levels of cocaine, nicotine, cannabis, opioids, and amphetamines in the sewage. Now, the scientists are collaborating with non-profits that test the health of the city’s waterways, trying to correlate levels of pharmaceuticals in our rivers with the amount of harmful bacteria.

To Dr. Cheng and Dr. Concheiro-Guisan, wastewater analysis’s great strength lies in early warning and early intervention. “It’s a great tool for prediction, for public health, crime fighting, and disease [prevention] purposes,” says Dr. Cheng. “The official report is often too late, but if you can do an early intervention, find the issue and start addressing it, there’s a lot you can do.”

“We looked at wastewater because we saw the utility,” says Dr. Concheiro-Guisan. “This is a different application [than viral tracking] but with the same thought: that what we eliminate from our bodies tells you a lot about your population.”

However, the United States is late to the game. Though the CDC has had results with its national COVID-19 tracking program, both researchers lament the lack of a centralized American body to apply this research to other public health applications. They’d like to see the U.S. follow the example set in European countries, China, Australia, and increasingly in South America, where governments have applied wastewater sampling to create campaigns warning their citizens about novel psychoactives, catch drug manufacturers, and more.

“It’s a very important public health tool that is showing results,” says Dr. Concheiro-Guisan. “If you start in the biggest city in the country, if you start in New York, then others will follow.”

Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng is an Associate Professor and Chair of John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research is in the areas of toxicology and forensic pharmacology, including the roles that environmental toxins play in neurodegenerative diseases, identifying the target genes and signaling pathways affected by environmental toxins, and investigating pharmacological mechanisms of anti-cancer medications.

Dr. Shu-Yuan Cheng is an Associate Professor and Chair of John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research is in the areas of toxicology and forensic pharmacology, including the roles that environmental toxins play in neurodegenerative diseases, identifying the target genes and signaling pathways affected by environmental toxins, and investigating pharmacological mechanisms of anti-cancer medications.

Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan is Assistant Professor of Forensic Toxicology in John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research focuses on the development and validation of analytical methods by gas and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and their application to different specimens, the detection of drug exposure during pregnancy, and the toxicological study of new psychoactive substances.

Dr. Marta Concheiro-Guisan is Assistant Professor of Forensic Toxicology in John Jay’s Department of Sciences. Her research focuses on the development and validation of analytical methods by gas and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and their application to different specimens, the detection of drug exposure during pregnancy, and the toxicological study of new psychoactive substances.

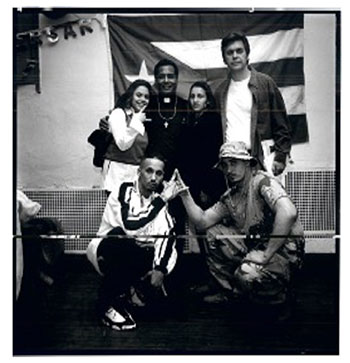

Critical Sociology At Work Around the Globe – David Brotherton and the Social Change Project

Dr. David Brotherton is in high demand. As founder and director of the Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project, a research project at John Jay, he leads grants that span multiple countries and touch subjects from post-release reintegration to immigration and the deportation pipeline. His long background and expertise in critical criminology and sociology have suited him to lead the varied types of prestigious grants the project obtains. Brotherton says that the work has three key points of overlap: “One part is to be able to transcend the academy, to translate your findings from the theory to what it actually means to people. Second, you’re doing work that immediately has an impact, to understand or respond to a social problem. And the third thing is to work with the underrepresented, the marginalized, and to help develop knowledge that goes back to them, to empower them.”

With a mission statement like that, how could the Social Change Project not have ended up at John Jay College? Founded in 2017, the organization almost lived at the CUNY Graduate Center; however, a set of happy accidents brought it to John Jay, where, co-directed by Brotherton and Professor of Sociology Dr. Jayne Mooney, it has been funded every year. Under the project’s umbrella live two working groups: the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime, a working group that focuses on “crimmigration” and the dynamics of border control and migrant detention, and the Critical Social History Project, which features Mooney’s work chronicling the history of incarceration in New York. Today, the Social Change Project is doing work with ramifications that will be felt all over the globe.

The Deportation Pipeline

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

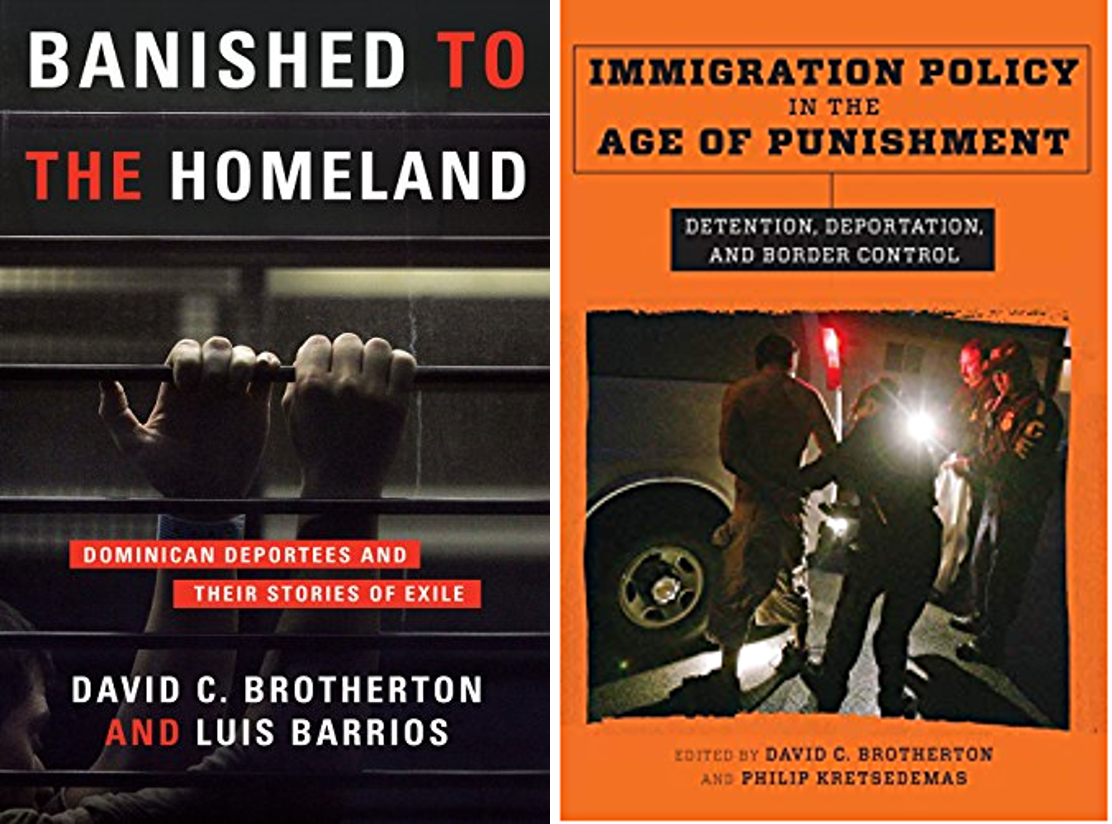

As he tells the story, Brotherton’s work with infamous gang organization the Latin Kings in New York brought him to the Dominican Republic in the early 2000s, where he was giving a talk on his project. “People didn’t want to know about the gangs, all they wanted to know was, why are you sending them all back here?” says Brotherton. “And I said, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll find out.’” That was the start of his investigations into transnational gangs and the issue of deportation, which at the time was not well-studied. That work has led to multiple grants and studies, books including Banished to the Homeland: Dominican Deportees and Their Stories of Exile and Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, Border Control, and the evolution of the multinational TRANSGANG project in Europe, which he advises.

This spring, Brotherton’s project will be working with personnel from Rutgers, including John Jay College graduate Sarah Tosh, to kick off the Deportation Pipeline Project, funded by the National Science Foundation. The team will interview a variety of subjects – immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, including some who have been detained for deportation hearings; lawyers; judges; and even ICE agents if possible – to understand the racialized “deportation pipeline” that runs through NYC back to the Caribbean, and the current situation these communities are living through under the Biden Administration.

“We need to understand all this, and then we’re going to be looking at all the texts that come down, the sanctions, all the laws. We know that Biden has said we’re going after criminal agents and gang members, which is just carrying on from Trump, but I thought we were supposed to have a new, more humane approach. So is it new wine in old bottles or are we going to get a real change in behavior? I don’t know.”

The two-year study will culminate in a book on the topic, as well as a conference with representatives from other municipalities. But Brotherton is already looking past the conclusion of the research to a potential comparative study in another large city or small town, to understand the dynamics of deportation in other American environments with similar demographics being targeted by immigration officials.

Critical Gang Studies

The Social Change Project is also looking forward to wrapping up several projects in the coming months. Since 2019, Brotherton has been consulting for the World Bank in El Salvador, developing national strategies for rehabilitation and reinsertion programs for formerly-incarcerated gang members in that country, which has the second-highest rate of imprisonment in the world after the United States. In April the project published a paper summarizing those findings, and expanding on them. “As we were writing this, we realized there is no real program for rehabilitation anywhere in Latin America, no probation, nothing like that,” says Brotherton. “Once you come out of prison, you’re on your own. So what we’re developing for El Salvador is really a model for the whole of Latin America.”

And July will see the publication of an edited volume, the Routledge International Handbook of Critical Gang Studies, which Brotherton edited along with Rafael Jose Gude, a Research Fellow at the Social Change Project. The book, which includes chapters by a number of CUNY faculty and graduates, will offer new perspectives on gang studies, placing them in the context of their political and social environments. According to Brotherton, it will cover perhaps 18 different countries and will be the largest handbook Routledge has ever released at nearly 900 pages long.

Incarceration and the Credible Messengers

Finally, Brotherton is working on a book on the Credible Messenger phenomenon, due out in 2022. The book, titled What’s Love Got To Do With It?: Credible Messengers and the Power of Transformative Mentoring, begins with a history of the now-widespread program, which recruits the formerly-incarcerated to intervene with young, at-risk kids from their neighborhoods, to keep them away from involvement with the criminal legal system. The book also incorporates qualitative research, including interviews with Messengers, kids, and administrators, as well as the currently incarcerated.

The Social Change Project and Brotherton himself are juggling many projects, each with many moving parts. But Brotherton relies on the connections he’s made over his career teaching at both John Jay and the CUNY Graduate Center, and doing research around the world, to keep the plates spinning. “It’s difficult,” he says. “Sometimes it gets overwhelming, but I always try to make sure I’ve got really good people in each project.”

At the end of the day, Brotherton is proud to be doing work that makes a difference for underserved, understudied communities that can face immense challenges. “I think the project carries on a rich tradition at John Jay. We’re following that tradition of socially conscious, critical social science.”

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Frank Pezzella Wants Increased Accountability on Hate Crime Reporting

During the chaotic years of the Trump Administration, the United States experienced a rise in hate crimes. This increase has been confirmed by FBI data collection, media reporting, and independent scholarship. According to Dr. Frank Pezzella, an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College and a scholar of hate crimes, four out of the past five years, from 2015 to 2019, have seen consecutive increases in hate crime offending in this country, something he says is new. Nine of the ten largest American cities had the most dramatic increases in hate crimes – including New York City.

Hate crimes, or bias crimes, are strictly defined by the FBI. The organization sets out 14 indicators that must be present for a criminal offense to be classified as a hate or bias crime, that provide objective evidence that the crime was motivated by bias. But according to Dr. Pezzella, the evidence to meet those criteria isn’t always clear. Not every hate crime is as flagrant as the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016 or the 2018 attack on Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue. To establish a hate crime was committed, first responding police officers must look for evidence of bias motivation – what Pezzella calls an “elevated mens rea” requirement. But bias can only be committed against legally protected categories, like race and ethnicity, sexual or gender orientation, disability, or religion, which vary from state to state. And the additional paperwork and procedural requirements that come with classifying an incident as a hate crime are, in his words, disincentivizing police reporting.

Undercounting Hate Crimes

The result of these complications is rampant underreporting. In his new book, The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America, Dr. Pezzella looks at the reasons why hate crimes are so undercounted in the United States, and proposes some solutions for what law enforcement and policymakers can do to correct the issue. Since the enactment of the federal Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990, which required the Attorney General to collect data about hate crimes, the FBI has been fulfilling this mandate in the form of the Hate Crime Statistics Program, published annually as part of the Uniform Crime Report. According to Dr. Pezzella, since 1990 the UCR has reported an average of roughly 8,000 hate crimes per year; but victims, he says, report around 250,000 hate crimes per year. He attributes this substantial gap to a variety of factors including the evidentiary and procedural barriers noted above. In addition, only about 100,000 of these victimizations are ever reported to the police in the first place. And when victims do report, police departments are under no legal requirement to pass their findings on to the FBI.

The result of these complications is rampant underreporting. In his new book, The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America, Dr. Pezzella looks at the reasons why hate crimes are so undercounted in the United States, and proposes some solutions for what law enforcement and policymakers can do to correct the issue. Since the enactment of the federal Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990, which required the Attorney General to collect data about hate crimes, the FBI has been fulfilling this mandate in the form of the Hate Crime Statistics Program, published annually as part of the Uniform Crime Report. According to Dr. Pezzella, since 1990 the UCR has reported an average of roughly 8,000 hate crimes per year; but victims, he says, report around 250,000 hate crimes per year. He attributes this substantial gap to a variety of factors including the evidentiary and procedural barriers noted above. In addition, only about 100,000 of these victimizations are ever reported to the police in the first place. And when victims do report, police departments are under no legal requirement to pass their findings on to the FBI.

“Of the roughly 18,500 police departments, only maybe 75% participate in the Uniform Crime Report hate crime reporting program – note that it is voluntary,” says Pezzella. “So we don’t even know about hate crimes in 25% of precincts. And of the participating 75%, roughly 90% report zero hate crimes every year. So one of the reasons we wrote the book is that, either we don’t have hate crimes the way we think we do, or we have a systemic reporting problem.” It’s obvious which he believes is true.

The consequences of underreporting hate crimes are severe, Dr. Pezzella says. “To the extent that we underreport both the type and extent of victimization, it really does put a specific policy issue in front of us. We need to know who’s being affected, how they’re being affected, and the extent of the effect, in order to fashion remedies.” The only way to target treatment and services for the most vulnerable and likely victims is through accurate reporting.

Remedying Undercounting

In order to remedy undercounting and better target policy, Dr. Pezzella presents a number of recommendations in The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America. He calls for changes to take place within police departments, at the level of state and local politics, and in the criminal legal system. First, he suggests that every precinct have a written and clearly posted hate crime policy, and that every officer be trained to understand the rules for identifying bias crimes and the statutes governing them in their particular state. He would also like to see greater police-community engagement on this issue, with better tracking of non-criminal bias incidents – like seeing a swastika or other racist tag in the neighborhood – which Pezzella says often lead to violent bias crimes. He would especially like to see hate crime reporting made mandatory, with penalties or audits following a departmental report of zero bias crimes in a year.

Stepping out of police departments, Dr. Pezzella also calls for greater engagement from state and local politicians, who after all control the purse strings as well as set state legislation, but who are often hesitant to call attention to a problem with hate crimes in their district. Finally, he wants prosecutors’ offices to commit to seeking hate crime convictions, rather than settling for the easier task of convicting an offender for non-bias equivalents. With every actor across the board invested in tackling hate crimes and being transparent and proactive about applying best practices, offenders are put on notice that the community, including police, won’t allow these harmful crimes to continue.

Vicarious Victimization

Dr. Pezzella has been studying hate crimes since his graduate school years at SUNY-Albany, but he doesn’t feel he’s reached the end of this line of research. Going forward, he is interested in studying the deleterious and vicarious effects hate crimes can have on the victims’ communities. Because bias-motivated offenders target victims based on what they are rather than what they do, Dr. Pezzella says, there is a sense that anyone could become the next victim. This impersonal threat undermines societal ideals of trust and equality, and can even affect property values, as whole groups feel unsafe in certain areas and may be forced to relocate. Pezzella also mentions the psychological and emotional impacts of feeling under threat for simply being who and what you are. “When a victim goes home and says they were a victim of a hate crime, in what way does it impact the quality of life or sense of safety for secondary victims [i.e., the victim’s community]?” he asks. “What do they do? While we understand the direct impact, we know less about this vicarious impact, and how far it extends beyond the primary victim.”

He also has his eye on current events, especially the rise of domestic terrorism in the United States. Dr. Pezzella is concerned about the growing number of organized hate groups in recent years, and how emboldened they have been by rhetoric from the top levels of government. While many mass shootings have been categorized as domestic terrorism, Pezzella also sees evidence of bias that might categorize these events as hate crimes. If they are being left out of crucial counts that help to allocate resources and fight back against hate in this country, he wants to know.

Dr. Frank Pezzella is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College. His primary research focus is on the causes, correlates, and consequences of hate crimes victimizations. He also conducts research on issues that relate to race, crime and justice. In addition to his most recent book, he is also the author of Hate Crime Statutes: A Public Policy and Law Enforcement Dilemma, as well as numerous peer-reviewed articles.

Dr. Frank Pezzella is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College. His primary research focus is on the causes, correlates, and consequences of hate crimes victimizations. He also conducts research on issues that relate to race, crime and justice. In addition to his most recent book, he is also the author of Hate Crime Statutes: A Public Policy and Law Enforcement Dilemma, as well as numerous peer-reviewed articles.

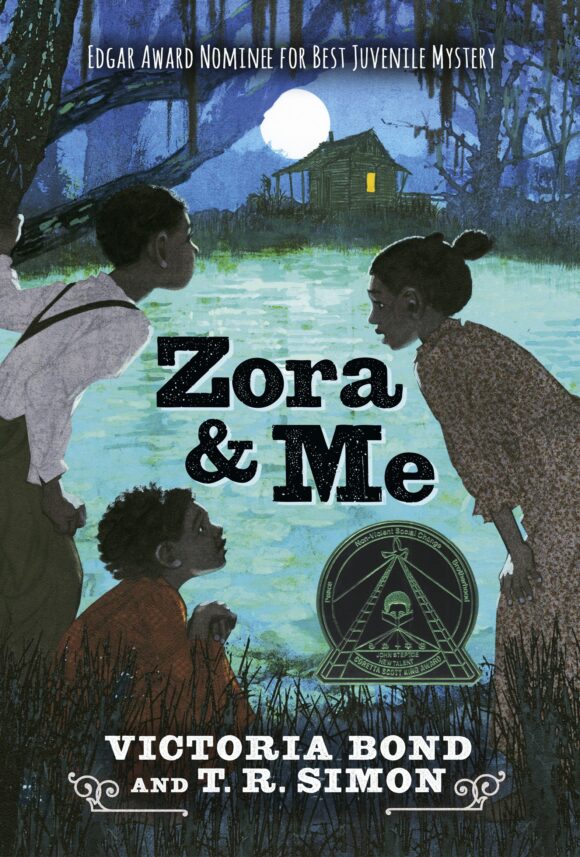

Victoria Bond’s ‘Zora and Me’ Trilogy Closes With ‘The Summoner’

Victoria Bond is a lecturer in John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s English Department, and the co-author with T. R. Simon of a series of young adult novels inspired by the childhood of American literary icon Zora Neale Hurston. The Zora and Me trilogy fictionalizes a young Zora as what The New York Times calls a “girl detective,” living in Hurston’s real-life hometown of Eatonville, Florida. Through the use of tropes from mystery and horror, the books explore community, and the fragility of justice for Black people.

In the first novel, Zora and Me, stories about a shape-shifter lead Zora and her best friend Carrie (the narrator) to solve a murder mystery. The second novel of the series, The Cursed Ground, sees Carrie and Zora learning more about the dark, unforgiveable history of slavery from a ghost. And in Bond’s latest and final novel, Zora and Me: The Summoner, Eatonville experiences upheaval that causes Zora’s family to seek their fortunes elsewhere. The use of zombies in this book, Bond says, is a way to explore the exploitation and trauma of African American lives.

Each installment of the trilogy may incorporate dark, scary elements, but, according to Kirkus Reviews, the brilliance of the novels is that they are able to render African American children’s lives during the Jim Crow era as “a time of wonder and imagination, while also attending to their harsh realities.”

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Alabama in 1891 and published several novels and many short stories, plays and essays, although she is best known for her classic Harlem Renaissance novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Zora and Me was the first novel not written by Hurston herself that has been endorsed by the Zora Neale Hurston Trust, founded in 2002. To bring the real Zora’s experiences in her hometown of Eatonville, Florida, to life, Bond and Simon researched Hurston’s life extensively by reading her biographies and her 1942 autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road. They sought to create a story right for young adult readers that was true to the historical period in which it takes place, and which features a smart, spirited Black girl with a vivid imagination, ready to inspire other girls.

Zora and Me: The Summoner is forthcoming from Candlewick Press on October 13, 2020, and available for preorder now. To learn more about Zora Neale Hurston from author Vicky Bond, watch her in this short video on YouTube. Or to learn more about the experience of writing a novel during these uniquely difficult times, read this post from the author.

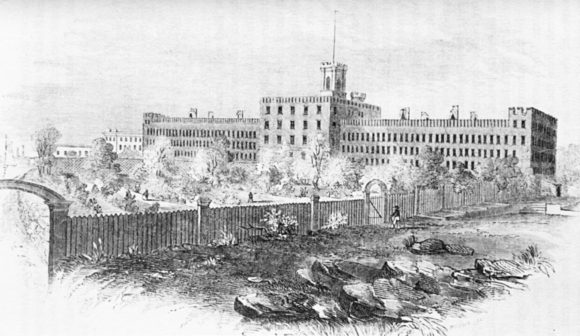

A Critical History of Incarceration in New York City

Dr. Jayne Mooney is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay and a member of the doctoral faculty of Women’s Studies and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is also a director and founding member of the Critical Social History Project (CSHP), a research initiative and part of John Jay’s Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project that draws on archival material to shed light on the history of incarceration in New York City.

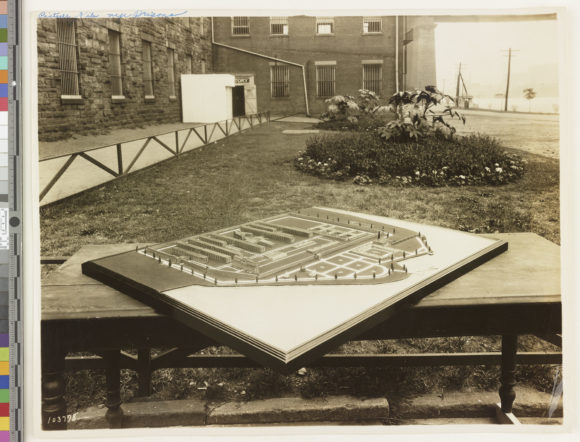

The project began in 2015 with a conversation spurred by reporting on abuse, poor conditions, and a rash of tragedies at Rikers Island; how best, Mooney and colleagues wondered, to preserve the memories of those who had been affected by the infamous jail, including not only the incarcerated but also their friends and families, guards and educators? And so they began the “Other City” project, which forms the largest component of the CSHP. Informed by their research into the history of New York’s penitentiary system, Mooney’s working group is pointing out the problems inherent in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration’s proposal to close Rikers and open four new city jails.

“On the most basic level, what we’re showing is that the current proposals are reinventing the wheel. It’s the same thing that’s always happened. Closing an institution and setting it up again, you’re going to have the same problems, because you’re not getting to those deep-rooted, structural issues,” says Mooney.

Reinventing the Wheel

In a forthcoming article, “Rikers Island: The Failure of a ‘Model’ Penitentiary” due to be published in The Prison Journal in 2020, Mooney and her co-author, CUNY graduate student Jarrod Shanahan, go through the instructive failures of incarceration reform in New York City back to the 1735 construction of the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction. They argue that a lack of historical documentation has allowed policymakers to strategically “forget” the failures of past “model” or “state of the art” institutions, continually replacing old jails with new without a look at the larger issues that have led to waves of highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful penal reform.

Set against the backdrop of historical, social and political context, Rikers’ closure and the proposals to replace it look familiar. “All of these places opened in the spirit of optimism—everything was going to change. And then everything goes wrong, these institutions are denounced as embarrassments, and the decision is made to close them down and rebuild. Of course, that’s what’s been happening in the present moment,” Mooney says. She and her colleagues encourage the Mayor’s Office to look beyond the walls of the prison for new solutions to social problems faced by New York and, indeed, the United States.

(Read her December 2019 letter to The Guardian on the subject, “Rikers has failed like others before it, but the solution is not new jails.”)

Preserving Voices, Preserving Justice

Mooney’s challenge to the new proposals is grounded not only in her work in political social history, but also in her background as a critical criminologist. “There’s a very strong abolitionist line all the way through critical criminology,” she notes, which informs the way the Critical Social History Project has approached critiques of the plan to build new jails.

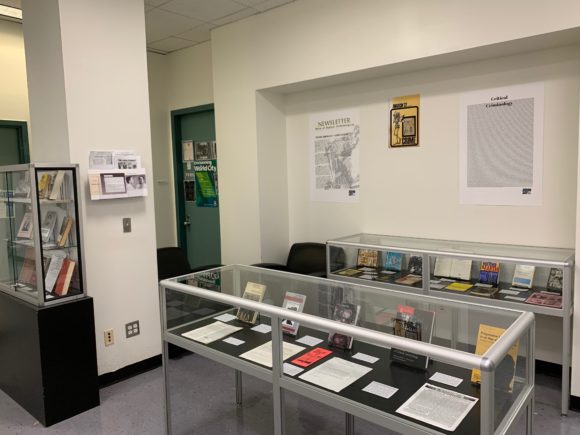

The CSHP isn’t only focused on documenting mass incarceration in NYC. As the Vice Chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Critical Criminology and Social Justice Division, as well as the archivist, Mooney has been accumulating archival information related to the division and the field’s history of activism. The CSHP’s Preserving Justice component, jointly directed by Mooney and Visiting Scholar Albert de la Tierra, has created an exhibition in the Sociology Department displaying some of the core critical criminology texts. It’s open to any students, faculty or staff who are interested in the history of the field and the work of its important thinkers.

Expanding Research Horizons

Mooney is proud to talk about her team of dedicated researchers, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students. With the help of their diverse experiences and interests, the Critical Social History Project is expanding its remit, from the history of Rikers Island to topics including the history of women’s incarceration, other New York carceral institutions including the Tombs and Sing-Sing, mental illness and incarceration, and more. Together, they are showing the persistence of the problems related to the history of mass incarceration, no matter where in history you begin your research—up to and including the present day.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

You can learn more by visiting the Critical and Social History Project’s website.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border. Eric Piza is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His research focuses on the spatial analysis of crime patterns, problem-oriented policing, crime control technology, and the integration of academic research and police practice. His recent research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals including Criminology, Criminology & Public Policy, Crime & Delinquency, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Justice Quarterly and more. In support of his research, Dr. Piza has secured over $2.2 million in outside research grants, including funding from the National Institute of Justice. In 2017, he was the recipient of the American Society of Criminology, Division of Policing’s Early Career Award in recognition of outstanding scholarly contributions to the field of policing.

Eric Piza is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His research focuses on the spatial analysis of crime patterns, problem-oriented policing, crime control technology, and the integration of academic research and police practice. His recent research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals including Criminology, Criminology & Public Policy, Crime & Delinquency, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Justice Quarterly and more. In support of his research, Dr. Piza has secured over $2.2 million in outside research grants, including funding from the National Institute of Justice. In 2017, he was the recipient of the American Society of Criminology, Division of Policing’s Early Career Award in recognition of outstanding scholarly contributions to the field of policing.

Recent Comments