Home » Posts tagged 'criminal justice reform'

Tag Archives: criminal justice reform

A Critical History of Incarceration in New York City

Dr. Jayne Mooney is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay and a member of the doctoral faculty of Women’s Studies and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is also a director and founding member of the Critical Social History Project (CSHP), a research initiative and part of John Jay’s Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project that draws on archival material to shed light on the history of incarceration in New York City.

The project began in 2015 with a conversation spurred by reporting on abuse, poor conditions, and a rash of tragedies at Rikers Island; how best, Mooney and colleagues wondered, to preserve the memories of those who had been affected by the infamous jail, including not only the incarcerated but also their friends and families, guards and educators? And so they began the “Other City” project, which forms the largest component of the CSHP. Informed by their research into the history of New York’s penitentiary system, Mooney’s working group is pointing out the problems inherent in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration’s proposal to close Rikers and open four new city jails.

“On the most basic level, what we’re showing is that the current proposals are reinventing the wheel. It’s the same thing that’s always happened. Closing an institution and setting it up again, you’re going to have the same problems, because you’re not getting to those deep-rooted, structural issues,” says Mooney.

Reinventing the Wheel

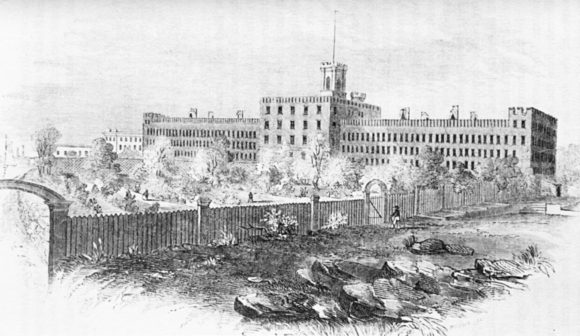

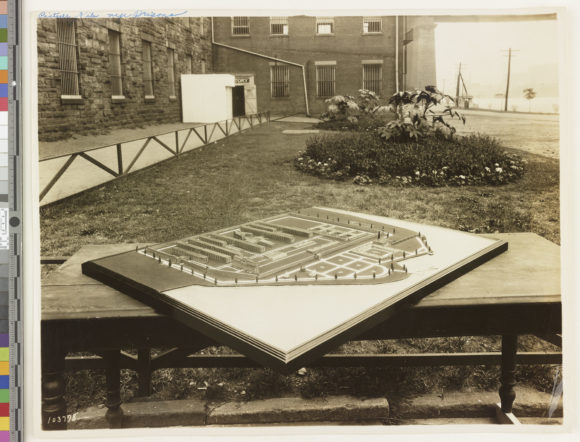

In a forthcoming article, “Rikers Island: The Failure of a ‘Model’ Penitentiary” due to be published in The Prison Journal in 2020, Mooney and her co-author, CUNY graduate student Jarrod Shanahan, go through the instructive failures of incarceration reform in New York City back to the 1735 construction of the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction. They argue that a lack of historical documentation has allowed policymakers to strategically “forget” the failures of past “model” or “state of the art” institutions, continually replacing old jails with new without a look at the larger issues that have led to waves of highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful penal reform.

Set against the backdrop of historical, social and political context, Rikers’ closure and the proposals to replace it look familiar. “All of these places opened in the spirit of optimism—everything was going to change. And then everything goes wrong, these institutions are denounced as embarrassments, and the decision is made to close them down and rebuild. Of course, that’s what’s been happening in the present moment,” Mooney says. She and her colleagues encourage the Mayor’s Office to look beyond the walls of the prison for new solutions to social problems faced by New York and, indeed, the United States.

(Read her December 2019 letter to The Guardian on the subject, “Rikers has failed like others before it, but the solution is not new jails.”)

Preserving Voices, Preserving Justice

Mooney’s challenge to the new proposals is grounded not only in her work in political social history, but also in her background as a critical criminologist. “There’s a very strong abolitionist line all the way through critical criminology,” she notes, which informs the way the Critical Social History Project has approached critiques of the plan to build new jails.

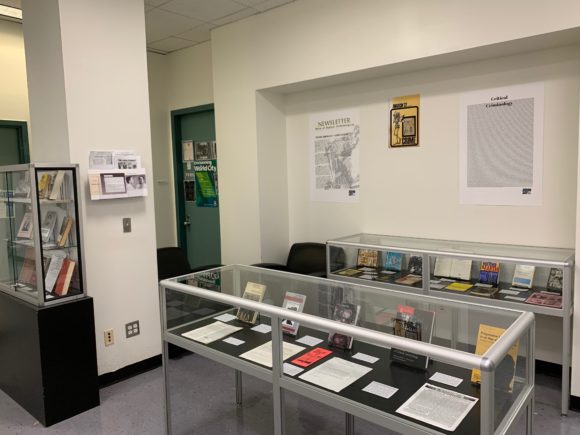

The CSHP isn’t only focused on documenting mass incarceration in NYC. As the Vice Chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Critical Criminology and Social Justice Division, as well as the archivist, Mooney has been accumulating archival information related to the division and the field’s history of activism. The CSHP’s Preserving Justice component, jointly directed by Mooney and Visiting Scholar Albert de la Tierra, has created an exhibition in the Sociology Department displaying some of the core critical criminology texts. It’s open to any students, faculty or staff who are interested in the history of the field and the work of its important thinkers.

Expanding Research Horizons

Mooney is proud to talk about her team of dedicated researchers, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students. With the help of their diverse experiences and interests, the Critical Social History Project is expanding its remit, from the history of Rikers Island to topics including the history of women’s incarceration, other New York carceral institutions including the Tombs and Sing-Sing, mental illness and incarceration, and more. Together, they are showing the persistence of the problems related to the history of mass incarceration, no matter where in history you begin your research—up to and including the present day.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

You can learn more by visiting the Critical and Social History Project’s website.

John Jay Featured Grant – Reducing Prison Overcrowding: Jeff Mellow + Deborah Koetzle

John Jay faculty and staff came together for a reception on May 14th to honor 76 of their own who received major and external grants and awards in 2018. The funded projects are a testament to the hard work John Jay’s community devotes to research and to honorees’ dedication to studies and creative work that strengthen the scholarly fabric of the institution. The awards funded projects of all types, from those with potential therapeutic implications to those that could change international policy, and more.

Among the honorees were Dr. Jeff Mellow and Dr. Deborah Koetzle. Their grant, from the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, took them to El Salvador to work on alleviating the severely overcrowded conditions in many Salvadoran prisons.

Both Dr. Mellow and Dr. Koetzle have been working to apply evidence-based, empirically-verified practices to corrections for many years, so when the opportunity came to apply their knowledge gained from research in the United States to an international setting, they knew they had to take it. The project took place in cooperation with El Salvador’s National Criminological Council and Director of the General Office of Penal Centers.

Prison overcrowding

El Salvador’s rate of incarceration is among the highest in the world — second only to the United States, with more than 600 out of every 100,000 persons incarcerated. Although the overcrowding rate is slowly coming down thanks to the construction of new prison facilities, the researchers described unhealthy conditions in some prisons. Some facilities were at 800 or 900 percent capacity, with bunks overfilled with bodies, increased risk of infectious disease, and insufficient room for programming or recreation.

Dr. Koetzle described the severely overcrowded prisons as “strangely quiet” and very still, as inmates have little room for movement. “No one should have to live in those types of conditions,” said Koetzle. “But the other side of that is really seeing the government and the system putting forward meaningful, genuine efforts to address it.”

Releasing the bottleneck

The counterpart to overcrowded higher security institutions are the granjas, or minimum security prisons, to which incarcerated individuals can transition as part of their rehabilitative journey toward release. Their gradual reintegration and movement through the system requires a protracted process of repeated assessments. “Inmates have to both finish a minimum of a third of their sentence, and also engage in very extensive programming to move from closed prisons to open prisons,” said Mellow. “But the problem is there’s a bottleneck, and only about 6% of the inmates, out of 40,000, are in the open prisons.”

As part of the government’s effort to ameliorate prison conditions and move people through the system more quickly, the researchers were engaged to hire, train and manage criminological teams — composed of one lawyer, one educator, one psychologist and one social worker — that helped to build capacity to assess inmate progress toward rehabilitation while drafting more than 2,000 proposals to improve the process based on empirical data collected throughout.

“Our goal was to improve the correctional system and policies, to maintain our relationships down there, and help [the government] to introduce additional evidence-based practice and risk assessments that we think can really help them open up bottlenecks and be more efficient and effective in identifying low-risk individuals to move them through the rehabilitative phases,” said Mellow.

“Our goal was to improve the correctional system and policies, to maintain our relationships down there, and help [the government] to introduce additional evidence-based practice and risk assessments that we think can really help them open up bottlenecks and be more efficient and effective in identifying low-risk individuals to move them through the rehabilitative phases,” said Mellow.

They brought to the process many collective years of experience in working to introduce standardized, evidence-based practice to the U.S. correctional system. Both professors also brought back lessons learned from their time in El Salvador that could translate to better practice in the United States, emphasizing the ways Salvadorans involved in the justice system are still encouraged to feel a part of their community on the outside. “They have families much more engaged, and they are really trying to provide for employment opportunities,” remarked Koetzle. “I think on those two fronts in particular, we could learn.”

Mellow also outlined elements of the rehabilitation program, broadly called “Yo Cambio,” that he felt were exceptional, including “conjugal visits, which we rarely do in the United States, and focus on vocational education. They also have a Fair Day where inmates will go out to sell all the wares they’ve made inside the prison, and the national Olympic game day. You can see that they are really trying to show that inmates are part of the community. They’re people.”

The life of a PI

Working on a large international grant was both a challenge and a source of immense satisfaction. “You’re wearing 100 different hats,” said Mellow, who was Primary Investigator on the grant. “Everything from drafting subcontracts to thinking about lunch for the trainings, to dealing with messages every day, getting everybody paid, and dealing with the funder. Plus doing the actual work, and writing the quarterly and final reports and analyzing the evaluation. If you think about it, you’re managing 40-something people.”

It was “not typical to have so many staff in institutions for this length of time,” added Koetzle, the project’s Senior Advisor. “[And] engaging in international work stretches you a little bit differently.” They took seven trips to El Salvador during the two-plus years of their grant work, and talked about the greater investment of resources, time and flexibility needed to pull off a successful overseas project.But the challenges created by managing a large grant from so far away were paired with a huge pay-off. Both Mellow and Koetzle agreed this was one of the most rewarding projects they’d ever undertaken, and talked about the valuable insights they had learned from working in a different context and system. They also had only positive things to say about their team of local staff, both about their capabilities and their constant enthusiasm and dedication.

“That’s something that really stood out — the number of times they thanked us for giving them the opportunity to help their country,” said Koetzle.

Next steps

Now that the grant has ended, as of February 2019, Dr. Mellow and Dr. Koetzle, along with co-PI and Senior International Officer in John Jay’s Office of International Studies and Programs Mayra Nieves and their program coordinator, PhD candidate and Salvadoran native Lidia Vásquez, are looking ahead. They are working on publishing their results with a Salvadoran university, in Spanish, and would like to see some of their recommendations translated to national policy. Their greatest hope, though, is to find continuing funding to keep doing the work to which they’ve dedicated so much time over the last two years, and perhaps even extend its scope to other nations in Central and South America with similar overcrowding and assessment challenges in their own criminal justice systems.

“We are hoping for the project to come back, “said Mellow. “That is our goal.”

Dr. Jeff Mellow is a Professor in John Jay College’s Criminal Justice Department, Director of the Criminal Justice MA Program, and a member of the doctoral faculty at the CUNY Grad Center. His research focuses on correctional policy and practice, program evaluation, reentry, and critical incident analysis in corrections.

Dr. Jeff Mellow is a Professor in John Jay College’s Criminal Justice Department, Director of the Criminal Justice MA Program, and a member of the doctoral faculty at the CUNY Grad Center. His research focuses on correctional policy and practice, program evaluation, reentry, and critical incident analysis in corrections.

Dr. Deborah Koetzle is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Management at John Jay College and the Executive Officer of the Doctoral Program in Criminal Justice. Her research interests center around effective interventions for offenders, problem-solving courts, risk/need assessment, and cross-cultural comparisons of prison-based treatments.

Dr. Deborah Koetzle is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Management at John Jay College and the Executive Officer of the Doctoral Program in Criminal Justice. Her research interests center around effective interventions for offenders, problem-solving courts, risk/need assessment, and cross-cultural comparisons of prison-based treatments.

Dr. Phillip Atiba Goff – Data Science for Justice

On April 16, 2019, John Jay College’s Franklin A. Thomas Professor in Policing Equity Dr. Phillip Atiba Goff spoke at Session 4 of TED2019 in Vancouver. The program featured eight speakers representing eight projects that are receiving funding from The Audacious Project in 2019. Dr. Goff spoke on behalf of his independent non-profit organization, the Center for Policing Equity (CPE), which was one of this year’s Audacious Projects.

CPE focuses on addressing racism in the United States. According to Dr. Goff, “When we change the definition of racism from attitudes to behaviors, we transform that problem from impossible to solvable.” CPE’s project, COMPSTAT for Justice, is a database leveraging data collected from police departments and cities on police behavior in an effort to identify problem areas where specific police behaviors can change.

With the support of The Audacious Project, CPE wants to extend the results it’s already seen with partners adopting COMPSTAT for Justice, by delivering the project to police departments serving 100 million people across the United States over the next five years.

To hear Dr. Goff’s TED Talk, visit the @TEDTalks Twitter page, where the link to the livestream is still up. You can read more about Session 4 of TED2019 on the TEDBlog.

John Jay Scholars on the News — Re-enfranchising the Justice-Involved

In mid-April, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed an executive order re-enfranchising paroled persons with felony convictions. The move sidestepped the Republican-controlled state legislature and does not change state law; instead, the governor intends to issue pardons for individuals convicted of felonies and currently on parole in New York – up to 35,000 individuals – as well as pardoning any new felons entering the parole system each month. The order has been criticized on all sides, both for overstepping the bounds of gubernatorial power as well as for not going far enough to address criminal justice and electoral reform.

We asked some of our own faculty and staff what they thought of the move, and whether it might be a harbinger of further voting reform for the justice-involved, both in New York State and across the United States.

Gloria Browne-Marshall (Associate Professor, Constitutional Law): Only about seven nations disenfranchise formerly incarcerated citizens.

Alison Wilkey (Director of Public Policy, Prisoner Reentry Institute): The impacts of disenfranchisement on communities have intensified with mass incarceration. In 2016, the Sentencing Project estimated 6.1 million people were disenfranchised as the result of a felony conviction [in the United States].

Why is re-enfranchisement such a significant step? What do you believe the impact will be?

Dr. Baz Dreisinger (Professor, English): Denying those with justice involvement the right to vote is an unparalleled injustice. It’s about time that this be addressed.

Gloria: To withhold the right to vote due to a felony conviction is called a Civil Death. Re-enfranchisement is necessary for re-entry into society. To be placed outside of one’s community is the intended punishment. Once completed, the punished must be re-admitted into society as full members. This includes participation in the political process. All voting rights should be given once imprisonment has ended.

Alison: The right to vote is both a fundamental right and an important responsibility. Voting is the cornerstone of democracy and ensures that citizens are able to play a role in shaping our government. Re-enfranchising individuals on parole in New York State is a significant step towards ensuring a more participatory democracy and equitable society for all.

Governor Cuomo’s executive order will have significant impact on the re-entry process [i.e., individuals returning to society post-incarceration]. Successful re-entry often depends on opportunities for meaningful community engagement. Voting will ensure that individuals on parole have the opportunity to exercise their political voice and formally contribute to their communities.

Re-enfranchisement will also have a generational impact. According to the Urban Institute, 2.7 million children have an incarcerated parent, and more than 5 million children have had a parent in prison or jail at some point during their lifetimes. In many states, formerly incarcerated individuals are disenfranchised even post-sentence, after parole or probation. When parents or older family members are unable to participate in elections, children and younger generations lose their most direct model for civic engagement. Granting individuals on parole the right to vote will ensure that the children and family members of (formerly-) incarcerated individuals more often become involved in the political process.

Dr. Heath Brown (Associate Professor, Public Policy): Voting is one of the most important ways to participate in the democracy, so restoring voting rights is a meaningful way to encourage full participation and a truly just society. The impact of restoring voting rights will depend on actual registration and turnout, however. Unfortunately we do not make it very easy to register, even for those who are fully eligible. Voting is also not always easy, especially for those working long hours. Lowering all barriers to full democratic participation would be the best guarantee that all voices are heard on Election Day.

Do you believe there should be any qualifications or exceptions to re-enfranchising the formerly-incarcerated population?

Alison: PRI firmly believes that all individuals, regardless of their involvement in the justice system, should have the right to vote. There should be no moral or character requirement for enfranchisement.

What do you believe is the likelihood or rate at which this population might exercise their right to vote, if re-enfranchised?

Gloria: The Supreme Court is deciding a current case based on whether citizens have a right not to vote. The formerly convicted have a right not to vote. It’s their decision how and when they choose to exercise this and any other Constitutional right.

Alison: Re-enfranchisement will only be as successful as the attendant voter education effort, which needs to be proactive and accessible. Government agencies, community-based organizations, community leaders and grassroots groups have an obligation to communicate with individuals on parole to ensure robust voter registration and subsequent voter turnout.

Heath: Voting is a habit, so those who voted prior to incarceration likely will return to regular voting quickly. I worry more about those who were incarcerated as teens, having never voted. It is for these citizens that a thorough program of civic learning would be most beneficial. I hope colleges, like ours, and civic groups can come together to develop programs to encourage voting and teach about democratic practices. We shouldn’t accept voting as a right that only those citizens who feel most informed and comfortable do. Re-entry programs should add democratic participation to their already Herculean efforts. Under President Mason’s leadership, I hope the John Jay community will lead this movement to promote full voting participation.

Do you think this move by Governor Cuomo has the potential to influence or spread to other states? If so, which ones?

Heath: Substantial political science research shows that innovative state policies spread and diffuse to other states. When it comes to voting issues, partisan conflict will surely factor into whether other states look to New York and this recent decision.

Gloria: Hopefully, New York will influence New Jersey and other states with long parole and probation periods that leave some formerly incarcerated persons in a “civilly dead” limbo for nearly a decade.

Baz: Since this is an archaic, discriminatory and utterly ridiculous law, it seems inevitable that it will collapse nationwide.

Alison: Gov. Cuomo’s executive order represents a wider trend in criminal justice reform that addresses the impact of disenfranchisement. Currently, only Maine and Vermont have granted incarcerated individuals the right to vote. New Jersey is considering similar legislation, and Virginia Governor McAuliffe signed an executive order similar to Gov. Cuomo [in April 2016]. Moreover, the People’s Policy Project report Full Human Beings notes that “several pieces of legislation are being advanced to enfranchise every citizen silenced through incarceration” at both the state and federal levels.

Are you for extending the vote to currently incarcerated individuals as well? If so, should they be registered to vote in their home districts or the districts in which they are incarcerated?

Alison: PRI believes in giving incarcerated individuals the right to vote in their home communities. Participating in the electoral process in their home communities will help incarcerated individuals maintain a connection with their communities, promote civic engagement, and ensure that the wider communities’ needs are addressed.

Disenfranchisement of incarcerated individuals disproportionately affects black and Latinx urban communities, who account for 60% of the prison population but only 27% of the total population. While incarcerated individuals do not have the right to vote in New York, the state draws on census data to draw electoral districts, which counts these individuals as residents of the prison location, not at their home address. The Prison Policy Initiative notes that the majority of New York State’s prisons are built in white, rural communities, which results in the transfer of a “predominantly of-color, non-voting population to upstate prisons, where it is counted as part of the population base for state legislative redistricting, [and] artificially enhances the representation afforded to predominantly white, rural legislative districts.” As the People’s Policy Project report Full Human Beings points out, as a result of prison gerrymandering, “the collective concerns of urban communities of color then go unaddressed.”

Re-enfranchising incarcerated individuals will therefore impact local and national policy on issues that have a direct impact on communities with high rates of incarceration.

Gloria: Voting qualifications are determined by the states pursuant to the US Constitution. Good conduct has been considered a qualification for voting since the colonial era. So it would be difficult for states to allow the incarcerated to vote based on the conduct qualification, political expediency and distribution of power. With over 2 million incarcerated, the prisoner vote would greatly impact the political landscape. If the incarcerated could vote, then should they be able to run for office?

Alison Wilkey is Director of Public Policy at John Jay College’s Prisoner Reentry Institute. Alison joined the Prisoner Reentry Institute as the Policy Director in December 2015. Prior to joining PRI, she worked at Youth Represent as the Director of Policy and Legal Services, and as a staff attorney in the Criminal Defense Practice of the Legal Aid Society in Manhattan. Ms. Wilkey served on the Broad of Directors of the New York County Lawyers’ Association, serving on the Justice Center Advisory Board and numerous other committees. She sat on the Criminal Courts Committee and the Corrections and Community Reentry Committee of the New York City Bar Association. Ms. Wilkey is a graduate of Columbia Law School.

Dr. Baz Dreisinger is Professor of English at John Jay College. Dr. Dreisinger works at the intersection of race, crime, culture and justice. At John Jay she is the founding Academic Director of the college’s Prison-to-College Pipeline program, which offers college courses and re-entry planning to incarcerated men at Otisville Correctional Facility, and broadly works to increase access to higher education for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. Her most recent book, published in 2016, is Incarceration Nations: A Journey to Justice in Prisons Around the World.

Dr. Baz Dreisinger is Professor of English at John Jay College. Dr. Dreisinger works at the intersection of race, crime, culture and justice. At John Jay she is the founding Academic Director of the college’s Prison-to-College Pipeline program, which offers college courses and re-entry planning to incarcerated men at Otisville Correctional Facility, and broadly works to increase access to higher education for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. Her most recent book, published in 2016, is Incarceration Nations: A Journey to Justice in Prisons Around the World.

Gloria Browne-Marshall is an Associate Professor of Constitutional Law at John Jay College. Professor Browne-Marshall teaches classes in Constitutional Law, Race and the Law, Evidence, and Gender and Justice. She is a civil rights attorney, playwright, and the author of many articles and several books, including The Voting Rights War: The NAACP and the Ongoing Struggle for Justice, and Race, Law, and American Society: 1607 to Present.

Gloria Browne-Marshall is an Associate Professor of Constitutional Law at John Jay College. Professor Browne-Marshall teaches classes in Constitutional Law, Race and the Law, Evidence, and Gender and Justice. She is a civil rights attorney, playwright, and the author of many articles and several books, including The Voting Rights War: The NAACP and the Ongoing Struggle for Justice, and Race, Law, and American Society: 1607 to Present.

Dr. Heath Brown is an Associate Professor of Public Policy at John Jay College, City University of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. In addition to his teaching and research, Dr. Brown is Reviews Editor for “Interest Groups and Advocacy” and hosts a podcast called “New Books in Political Science,” where he interviews new authors of political science books. He is also an expert contributor to The Hill, The Atlantic magazine, and American Prospect magazine.

Dr. Heath Brown is an Associate Professor of Public Policy at John Jay College, City University of New York, and the CUNY Graduate Center. In addition to his teaching and research, Dr. Brown is Reviews Editor for “Interest Groups and Advocacy” and hosts a podcast called “New Books in Political Science,” where he interviews new authors of political science books. He is also an expert contributor to The Hill, The Atlantic magazine, and American Prospect magazine.

Recent Comments