Home » Posts tagged 'David Brotherton'

Tag Archives: David Brotherton

Critical Sociology At Work Around the Globe – David Brotherton and the Social Change Project

Dr. David Brotherton is in high demand. As founder and director of the Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project, a research project at John Jay, he leads grants that span multiple countries and touch subjects from post-release reintegration to immigration and the deportation pipeline. His long background and expertise in critical criminology and sociology have suited him to lead the varied types of prestigious grants the project obtains. Brotherton says that the work has three key points of overlap: “One part is to be able to transcend the academy, to translate your findings from the theory to what it actually means to people. Second, you’re doing work that immediately has an impact, to understand or respond to a social problem. And the third thing is to work with the underrepresented, the marginalized, and to help develop knowledge that goes back to them, to empower them.”

With a mission statement like that, how could the Social Change Project not have ended up at John Jay College? Founded in 2017, the organization almost lived at the CUNY Graduate Center; however, a set of happy accidents brought it to John Jay, where, co-directed by Brotherton and Professor of Sociology Dr. Jayne Mooney, it has been funded every year. Under the project’s umbrella live two working groups: the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime, a working group that focuses on “crimmigration” and the dynamics of border control and migrant detention, and the Critical Social History Project, which features Mooney’s work chronicling the history of incarceration in New York. Today, the Social Change Project is doing work with ramifications that will be felt all over the globe.

The Deportation Pipeline

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

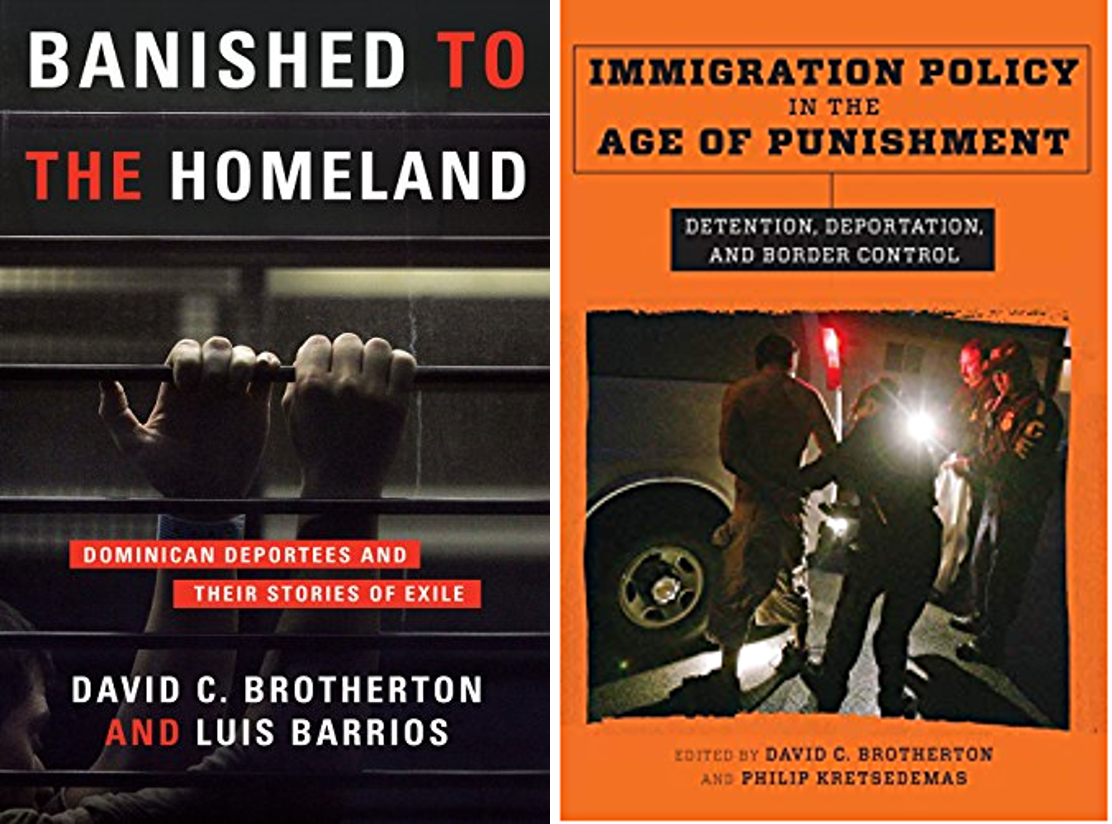

As he tells the story, Brotherton’s work with infamous gang organization the Latin Kings in New York brought him to the Dominican Republic in the early 2000s, where he was giving a talk on his project. “People didn’t want to know about the gangs, all they wanted to know was, why are you sending them all back here?” says Brotherton. “And I said, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll find out.’” That was the start of his investigations into transnational gangs and the issue of deportation, which at the time was not well-studied. That work has led to multiple grants and studies, books including Banished to the Homeland: Dominican Deportees and Their Stories of Exile and Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, Border Control, and the evolution of the multinational TRANSGANG project in Europe, which he advises.

This spring, Brotherton’s project will be working with personnel from Rutgers, including John Jay College graduate Sarah Tosh, to kick off the Deportation Pipeline Project, funded by the National Science Foundation. The team will interview a variety of subjects – immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, including some who have been detained for deportation hearings; lawyers; judges; and even ICE agents if possible – to understand the racialized “deportation pipeline” that runs through NYC back to the Caribbean, and the current situation these communities are living through under the Biden Administration.

“We need to understand all this, and then we’re going to be looking at all the texts that come down, the sanctions, all the laws. We know that Biden has said we’re going after criminal agents and gang members, which is just carrying on from Trump, but I thought we were supposed to have a new, more humane approach. So is it new wine in old bottles or are we going to get a real change in behavior? I don’t know.”

The two-year study will culminate in a book on the topic, as well as a conference with representatives from other municipalities. But Brotherton is already looking past the conclusion of the research to a potential comparative study in another large city or small town, to understand the dynamics of deportation in other American environments with similar demographics being targeted by immigration officials.

Critical Gang Studies

The Social Change Project is also looking forward to wrapping up several projects in the coming months. Since 2019, Brotherton has been consulting for the World Bank in El Salvador, developing national strategies for rehabilitation and reinsertion programs for formerly-incarcerated gang members in that country, which has the second-highest rate of imprisonment in the world after the United States. In April the project published a paper summarizing those findings, and expanding on them. “As we were writing this, we realized there is no real program for rehabilitation anywhere in Latin America, no probation, nothing like that,” says Brotherton. “Once you come out of prison, you’re on your own. So what we’re developing for El Salvador is really a model for the whole of Latin America.”

And July will see the publication of an edited volume, the Routledge International Handbook of Critical Gang Studies, which Brotherton edited along with Rafael Jose Gude, a Research Fellow at the Social Change Project. The book, which includes chapters by a number of CUNY faculty and graduates, will offer new perspectives on gang studies, placing them in the context of their political and social environments. According to Brotherton, it will cover perhaps 18 different countries and will be the largest handbook Routledge has ever released at nearly 900 pages long.

Incarceration and the Credible Messengers

Finally, Brotherton is working on a book on the Credible Messenger phenomenon, due out in 2022. The book, titled What’s Love Got To Do With It?: Credible Messengers and the Power of Transformative Mentoring, begins with a history of the now-widespread program, which recruits the formerly-incarcerated to intervene with young, at-risk kids from their neighborhoods, to keep them away from involvement with the criminal legal system. The book also incorporates qualitative research, including interviews with Messengers, kids, and administrators, as well as the currently incarcerated.

The Social Change Project and Brotherton himself are juggling many projects, each with many moving parts. But Brotherton relies on the connections he’s made over his career teaching at both John Jay and the CUNY Graduate Center, and doing research around the world, to keep the plates spinning. “It’s difficult,” he says. “Sometimes it gets overwhelming, but I always try to make sure I’ve got really good people in each project.”

At the end of the day, Brotherton is proud to be doing work that makes a difference for underserved, understudied communities that can face immense challenges. “I think the project carries on a rich tradition at John Jay. We’re following that tradition of socially conscious, critical social science.”

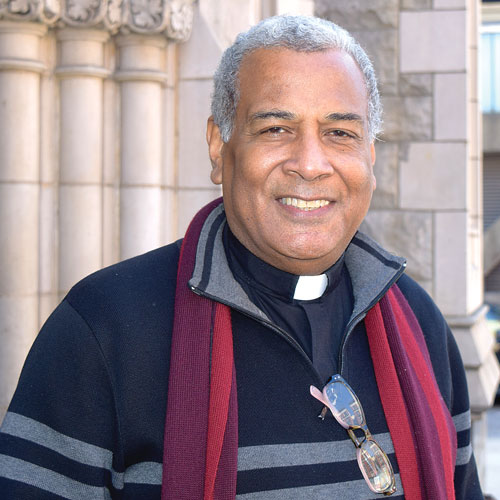

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Social Inclusion Leads to Violence Reduction in Ecuador – Dr. David Brotherton

Since 2007, the Ecuadorian approach to crime control has emphasized policies of social inclusion and innovations in criminal justice and police reform. One notable part of Ecuador’s holistic approach to public security was the decision to legalize a number of street gangs in 2007. The government claimed this decision contributed to the reduction of homicide rates from 15.35 per 100,000 in 2011 to close to 5 per 100,000 in 2017. Professor of Sociology David Brotherton was commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank to spend six months evaluating these claims through a qualitative research project focusing on the impact on violence reduction had by street gangs involved in processes of social inclusion. The results were published in 2018, arguing that social inclusion policies helped to transform gang members’ social capital into a vehicle for behavioral change. In December 2018, Dr. Brotherton was awarded a grant by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation to continue the work.

Since 2007, the Ecuadorian approach to crime control has emphasized policies of social inclusion and innovations in criminal justice and police reform. One notable part of Ecuador’s holistic approach to public security was the decision to legalize a number of street gangs in 2007. The government claimed this decision contributed to the reduction of homicide rates from 15.35 per 100,000 in 2011 to close to 5 per 100,000 in 2017. Professor of Sociology David Brotherton was commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank to spend six months evaluating these claims through a qualitative research project focusing on the impact on violence reduction had by street gangs involved in processes of social inclusion. The results were published in 2018, arguing that social inclusion policies helped to transform gang members’ social capital into a vehicle for behavioral change. In December 2018, Dr. Brotherton was awarded a grant by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation to continue the work.

What did you learn during the initial phase of your research?

We learned a lot. These are very large groups, with over 1,000 members spread across Ecuador, and they managed to create a new kind of culture within their organizations that was pro-social, pro-community, with a strong element of conflict resolution and mediation, cultures where they were working as partners with the government and non-state actors like universities on progressive agendas. They were partners in pro-social activities, everything from creating new youth cultures to voting, job training, and strengthening local communities, all of which you don’t associate with street gangs. And in their ranks are the most marginalized youth of their country, so they can reach kids that are so marginal that other organizations don’t reach them, even indigenous kids from the Amazon, and it is so important to bring them in and work with them. This is all across Ecuador.

When we asked the members what had changed, they said they don’t get into the same level of conflict. Where there might have been a previous period where they were at war with one another, they were able to end it with the government playing a role.

Sometimes these interventions don’t last very long, once the money runs out, but here you had a government that constantly maintained a presence and lived up to its promises, so the trust level became really high.

The end result is not necessarily unique, we’ve seen this in other places like with the Latin Kings in New York and various places in Spain, but the outcome across ten years was quite remarkable. Homicide rates are so indicative of a country’s ability to resolve tension, so when you see the inarguable statistics of homicides going down every year for ten years — it’s related to different factors, they also reformed the police department, but when you see that kind of result it’s pretty impressive.

What key aspects of the inclusion policy allowed gangs to successfully transition from criminal to purely social organizations?

The government recognizes that they won’t change overnight, because the economic situation doesn’t allow that, but you make it such that whatever [gangs] are involved in doesn’t hurt the community, and there are other pathways they can move into and you are creating real opportunities. So what does that look like? It looks like being recruited into programs at the university to give you skills, diploma programs. And these kids become a kind of role model for their mates.

In addition to that, [all of the gangs] were incorporated as non-profit organizations, which allows them to get government grants to do things like community building. You’re not just rhetorically arguing for a new culture, you’re making a new culture and making it happen. Those joining the organization come in with a different set of expectations, and it has a tremendous ripple effect. They created a strata of professional workers.

Also, the police are told not to pick them up, or intervene in their meetings. And the kids don’t fear any kind of stigma, they’re not constantly being harassed. With the communitarian police force, they worked with the heads of the police. It’s a totally unique phenomenon, and flies directly in the face of what we’re pushing in the U.S., which is zero tolerance.

Where else might this social inclusion approach be effective in curbing violence?

I mean, it could be effective in the U.S. Social inclusion is the complete opposite of the repressive policy that nearly always leads to what we call deviant amplification. You need to stop the stigmatization and have meaningful relationships with street groups, with intermediaries from the government. In the U.S., the police are so strong that this is all very difficult.

To make this work anywhere, politically you need to make a decision about where to invest resources. [In Ecuador,] they didn’t invest in the military, they didn’t invest in massive tax breaks for corporations, in fact they did the opposite. They boosted money for culture and art. If you stick with these political decisions, they will pay dividends over time.

What is the next step in completing this research?

I have a full-time field researcher, Rafael Gude, who has been working in Ecuador since April, focusing on the relationship between the Catholic University of Quito and the Latin Kings and Queens. I’m going down myself July 3-15 to do field work both with the Latin Kings and Queens and to attend a big national meeting in Cuenca, then I travel to Las Esmeraldas, on the Pacific coast of Ecuador, where we will interview members of the third major street organization in Ecuador, called Masters of the Street. We want to understand the changes in that group and the roles of social and political empowerment in the reduction in violence.

Las Esmeraldas had the highest rate of violence, with a really high homicide rate of around 70 per 100,000, which is now down to 20, and it’s on the border with Colombia so this is the biggest drug trafficking area and also very poor. This is a completely different socio-economic context, and mainly black Ecuadorians, so we want to see how the whole issue of race works itself out as they’re trying the same policy.

Also, things have changed; although the same party is in power, it’s not the same government. We thought they were going to completely reverse the policy, but a number of media organizations got into this report, and I gave this big talk in Medellín last year, and it’s become a real media story about this success. So this government has maintained the same policy, and embraced it as much or more than the last government.

Right now, we are also looking to do work in the prisons where the inmate population has increased substantially in recent years and many of the incarcerated have joined the groups.

Why is it important to continue this research?

The importance of this work is that it demonstrates a viable alternative to “zero tolerance” and other repressive policies that led to the highest homicide rates in the world — for example, in Central America’s Northern Triangle. The topic has been covered by the BBC and is out in English, Spanish and Portuguese, with multiple other Latin American nations now taking notice, including the president of Mexico.

How does your research dovetail with the HFG Foundation’s mission?

The research meshed with their general focus; they’ve always supported innovative anti-violence or violence prevention studies. For them to come on board, it’s a big deal.

You can learn more about the first stage of this research via the report on the Inter-American Development Bank’s website, or by listening to him talk about his research on the BBC program The Inquiry (starts at 13:43) or on the Peter Collins Show podcast.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College and the CUNY Graduate center. He is the author of a number of books on gangs and immigration, most recently co-authoring Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, and Border Control. He is a founding member of the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime research working group based at the Center on Social Change and Transgressive Studies at John Jay.

CUNY Graduate Center Hosts Press Briefing by Immigration Experts

August 8, 2018 – The Graduate Center of CUNY has the benefit of some of the best immigration scholars in the country. Ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, in which this contentious issue will play (and has already been seen to play) a big role, six distinguished faculty experts on immigration sat down to brief the press on a variety of issues surrounding evolving immigration policy under the Trump administration and related issues, including demographics, economics, and the sociocultural experience of immigrants in the United States.

The panel kicked off with CUNY Graduate Center Distinguished Professor of Sociology Richard Alba, who introduced the idea that immigration policy under President Trump is the most restrictionist and selective this country has seen since the inter-war period of the 1920s. However, he suggested that there are a number of structural constraints on this administration’s ability to push immigration restrictions too far. These include business’s need for new workers, both skilled and unskilled; demographic indicators of an impending dearth of young workers; and a lack of political will even among a Republic Congress to enact major immigration legislation.

Next, David Brotherton, a professor of sociology and criminologist from John Jay College, brought up the idea that the “deportation regime” under Donald Trump is not unique in the history of the United States. He noted earlier examples of deportation- or exclusion-oriented federal policy, including the 1996 Immigrant Responsibility Act, Indian Removal Act, and the 19th century Chinese Exclusion Act. Dr. Brotherton went on to discuss the origins of the Trump Administration’s restrictive immigration policies, particularly the president’s campaign tactics of stoking panic in a segment of the population that feels insecure about their place in society. He emphasized that this strategy represents only the latest in a series of moral panics in American history, calling back to the War on Drugs and earlier rhetoric about the dangers of young black and Latino men.

Dr. Brotherton described U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as arguably the “largest police force in the United States.” ICE’s detention and deportation of immigrants is retroactively punishing many non-native Americans for crimes in their pasts; because these individuals have since put down roots in the country, with families, jobs and wider communities that are hurt when they are suddenly taken away, the policy is cruel. For this reason, Dr. Brotherton has acted as an expert witness since 2007, testifying to the effects of deportation on the individuals detained, their communities, and even their representation.

A second immigration project that Dr. Brotherton is currently engaged in is “Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime,” in which he collaborates with Graduate Center faculty to treat New York City – a sanctuary city, and the only city that guarantees representation to immigrant detainees – as a case study. The project aims to look at this problem from all angles and account for many perspectives.

The next commentator was Margaret Chin, a professor of sociology at Hunter College, who focused on the problem of “glass and bamboo ceilings” that stand in the way of Asian-Americans’ achieving educational equity in New York City. She emphasized the importance of taking race into account when designing programs, such as student tracking and race-conscious admissions.

Nancy Foner, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, is the author of a number of books on immigration. During the briefing, she strove to correct immigration myths that are being spread by the president and members of his administration. First, that immigrants are criminals; in fact, immigrants commit less crime than native-born Americans (excepting immigration infractions), and cities and neighborhoods with higher concentrations of immigrant populations have lower rates of crime that comparable neighborhoods. Second, that today’s immigrant populations aren’t learning English; the “three-generation model” continues to be accurate in describing language-learning patterns in immigrant families. The United States can be called a “graveyard of languages” because immigrants tend to lose their native tongues in favor of English – typically by the third generation, individuals are mostly monolingual in English.

Debunking these myths, according to Dr. Foner, is important to reducing the hostility toward immigrants upon which the administration’s restrictive immigration agenda is predicated. She emphasized that social scientists and journalists alike have a responsibility to help publicize the truth about immigrants and their contributions to society.

According to Philip Kasinitz, a Presidential Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, the underlying strategy of the Trump Administration on immigration is difficult to understand, in that much of the policy is self-contradicting. He noted several key contradictions around the thinking on immigration today. For example, the current moral panic conflating immigrants, illegality and crime comes at a time when crime rates – particularly violent crime – is way down. Americans are also increasingly supportive of immigrants and their participation in society, but increasingly make a distinction between legal and illegal, creating a class of people involved socially, economically and culturally in our society but not politically, a fact that is, in his view, bad for a democratic society. Finally, Dr. Kasinitz talked about the generational factors behind a society that is increasingly diverse, but which at the same time harbors extreme anti-immigrant sentiments.

John Mollenkopf, Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Sociology, also noted contradictions inherent to the views of an older, white segment of the population: their anxiety about allowing immigrants into the country is not in their economic best interests, as many are increasingly dependent on low-wage immigrant labor for their care. As a scholar of the acquisition and use of political power, Dr. Mollenkopf opined that the best way to limit the ability of Republicans in Congress to build a base around anti-immigrant sentiment is to mobilize the increasing numbers of immigrant-origin voters and bring new constituencies into the electorate. In New York City, for example, the majority of the electorate is of immigrant origin, but newer immigrants have not yet organized to develop the same amount of political influence as groups that have been in the United States in large numbers for longer.

The panel wrapped up with questions from the audience. In particular, the discussion touched on the movement to abolish or reform U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an idea that has received some popular attention among Democrats in the lead up to the 2018 midterm elections. Dr. Brotherton said that “a critical mass of people has disappeared” in Latin American and Central American communities, and immigrants across the country have changed their routines out of fear of the agency. Dr. Kasinitz clarified that, despite popular belief, the number of deportations has not risen; rather, the length of immigrant detentions has grown substantially due to a lack of capacity in immigration courts to process detainees. All agreed that more dramatic action or a greater groundswell of support for reform is needed to signal that ICE’s actions are not acceptable to a majority of Americans.

For more information about the immigration research coming out of the CUNY Graduate Center, please visit the GC Immigration page.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border.

Recent Comments