Home » Posts tagged 'Jayne Mooney'

Tag Archives: Jayne Mooney

Critical Sociology At Work Around the Globe – David Brotherton and the Social Change Project

Dr. David Brotherton is in high demand. As founder and director of the Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project, a research project at John Jay, he leads grants that span multiple countries and touch subjects from post-release reintegration to immigration and the deportation pipeline. His long background and expertise in critical criminology and sociology have suited him to lead the varied types of prestigious grants the project obtains. Brotherton says that the work has three key points of overlap: “One part is to be able to transcend the academy, to translate your findings from the theory to what it actually means to people. Second, you’re doing work that immediately has an impact, to understand or respond to a social problem. And the third thing is to work with the underrepresented, the marginalized, and to help develop knowledge that goes back to them, to empower them.”

With a mission statement like that, how could the Social Change Project not have ended up at John Jay College? Founded in 2017, the organization almost lived at the CUNY Graduate Center; however, a set of happy accidents brought it to John Jay, where, co-directed by Brotherton and Professor of Sociology Dr. Jayne Mooney, it has been funded every year. Under the project’s umbrella live two working groups: the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime, a working group that focuses on “crimmigration” and the dynamics of border control and migrant detention, and the Critical Social History Project, which features Mooney’s work chronicling the history of incarceration in New York. Today, the Social Change Project is doing work with ramifications that will be felt all over the globe.

The Deportation Pipeline

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

As he tells the story, Brotherton’s work with infamous gang organization the Latin Kings in New York brought him to the Dominican Republic in the early 2000s, where he was giving a talk on his project. “People didn’t want to know about the gangs, all they wanted to know was, why are you sending them all back here?” says Brotherton. “And I said, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll find out.’” That was the start of his investigations into transnational gangs and the issue of deportation, which at the time was not well-studied. That work has led to multiple grants and studies, books including Banished to the Homeland: Dominican Deportees and Their Stories of Exile and Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, Border Control, and the evolution of the multinational TRANSGANG project in Europe, which he advises.

This spring, Brotherton’s project will be working with personnel from Rutgers, including John Jay College graduate Sarah Tosh, to kick off the Deportation Pipeline Project, funded by the National Science Foundation. The team will interview a variety of subjects – immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, including some who have been detained for deportation hearings; lawyers; judges; and even ICE agents if possible – to understand the racialized “deportation pipeline” that runs through NYC back to the Caribbean, and the current situation these communities are living through under the Biden Administration.

“We need to understand all this, and then we’re going to be looking at all the texts that come down, the sanctions, all the laws. We know that Biden has said we’re going after criminal agents and gang members, which is just carrying on from Trump, but I thought we were supposed to have a new, more humane approach. So is it new wine in old bottles or are we going to get a real change in behavior? I don’t know.”

The two-year study will culminate in a book on the topic, as well as a conference with representatives from other municipalities. But Brotherton is already looking past the conclusion of the research to a potential comparative study in another large city or small town, to understand the dynamics of deportation in other American environments with similar demographics being targeted by immigration officials.

Critical Gang Studies

The Social Change Project is also looking forward to wrapping up several projects in the coming months. Since 2019, Brotherton has been consulting for the World Bank in El Salvador, developing national strategies for rehabilitation and reinsertion programs for formerly-incarcerated gang members in that country, which has the second-highest rate of imprisonment in the world after the United States. In April the project published a paper summarizing those findings, and expanding on them. “As we were writing this, we realized there is no real program for rehabilitation anywhere in Latin America, no probation, nothing like that,” says Brotherton. “Once you come out of prison, you’re on your own. So what we’re developing for El Salvador is really a model for the whole of Latin America.”

And July will see the publication of an edited volume, the Routledge International Handbook of Critical Gang Studies, which Brotherton edited along with Rafael Jose Gude, a Research Fellow at the Social Change Project. The book, which includes chapters by a number of CUNY faculty and graduates, will offer new perspectives on gang studies, placing them in the context of their political and social environments. According to Brotherton, it will cover perhaps 18 different countries and will be the largest handbook Routledge has ever released at nearly 900 pages long.

Incarceration and the Credible Messengers

Finally, Brotherton is working on a book on the Credible Messenger phenomenon, due out in 2022. The book, titled What’s Love Got To Do With It?: Credible Messengers and the Power of Transformative Mentoring, begins with a history of the now-widespread program, which recruits the formerly-incarcerated to intervene with young, at-risk kids from their neighborhoods, to keep them away from involvement with the criminal legal system. The book also incorporates qualitative research, including interviews with Messengers, kids, and administrators, as well as the currently incarcerated.

The Social Change Project and Brotherton himself are juggling many projects, each with many moving parts. But Brotherton relies on the connections he’s made over his career teaching at both John Jay and the CUNY Graduate Center, and doing research around the world, to keep the plates spinning. “It’s difficult,” he says. “Sometimes it gets overwhelming, but I always try to make sure I’ve got really good people in each project.”

At the end of the day, Brotherton is proud to be doing work that makes a difference for underserved, understudied communities that can face immense challenges. “I think the project carries on a rich tradition at John Jay. We’re following that tradition of socially conscious, critical social science.”

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

A Critical History of Incarceration in New York City

Dr. Jayne Mooney is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay and a member of the doctoral faculty of Women’s Studies and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is also a director and founding member of the Critical Social History Project (CSHP), a research initiative and part of John Jay’s Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project that draws on archival material to shed light on the history of incarceration in New York City.

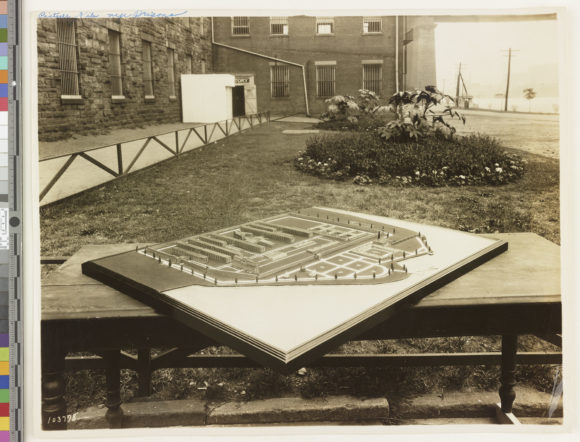

The project began in 2015 with a conversation spurred by reporting on abuse, poor conditions, and a rash of tragedies at Rikers Island; how best, Mooney and colleagues wondered, to preserve the memories of those who had been affected by the infamous jail, including not only the incarcerated but also their friends and families, guards and educators? And so they began the “Other City” project, which forms the largest component of the CSHP. Informed by their research into the history of New York’s penitentiary system, Mooney’s working group is pointing out the problems inherent in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration’s proposal to close Rikers and open four new city jails.

“On the most basic level, what we’re showing is that the current proposals are reinventing the wheel. It’s the same thing that’s always happened. Closing an institution and setting it up again, you’re going to have the same problems, because you’re not getting to those deep-rooted, structural issues,” says Mooney.

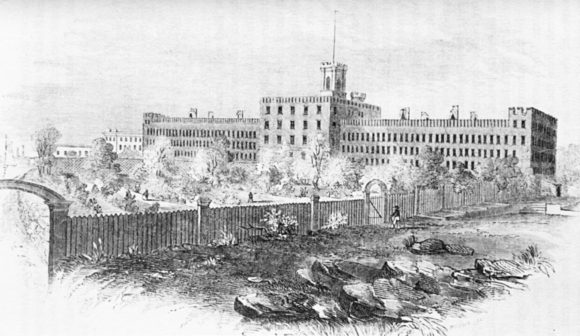

Reinventing the Wheel

In a forthcoming article, “Rikers Island: The Failure of a ‘Model’ Penitentiary” due to be published in The Prison Journal in 2020, Mooney and her co-author, CUNY graduate student Jarrod Shanahan, go through the instructive failures of incarceration reform in New York City back to the 1735 construction of the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction. They argue that a lack of historical documentation has allowed policymakers to strategically “forget” the failures of past “model” or “state of the art” institutions, continually replacing old jails with new without a look at the larger issues that have led to waves of highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful penal reform.

Set against the backdrop of historical, social and political context, Rikers’ closure and the proposals to replace it look familiar. “All of these places opened in the spirit of optimism—everything was going to change. And then everything goes wrong, these institutions are denounced as embarrassments, and the decision is made to close them down and rebuild. Of course, that’s what’s been happening in the present moment,” Mooney says. She and her colleagues encourage the Mayor’s Office to look beyond the walls of the prison for new solutions to social problems faced by New York and, indeed, the United States.

(Read her December 2019 letter to The Guardian on the subject, “Rikers has failed like others before it, but the solution is not new jails.”)

Preserving Voices, Preserving Justice

Mooney’s challenge to the new proposals is grounded not only in her work in political social history, but also in her background as a critical criminologist. “There’s a very strong abolitionist line all the way through critical criminology,” she notes, which informs the way the Critical Social History Project has approached critiques of the plan to build new jails.

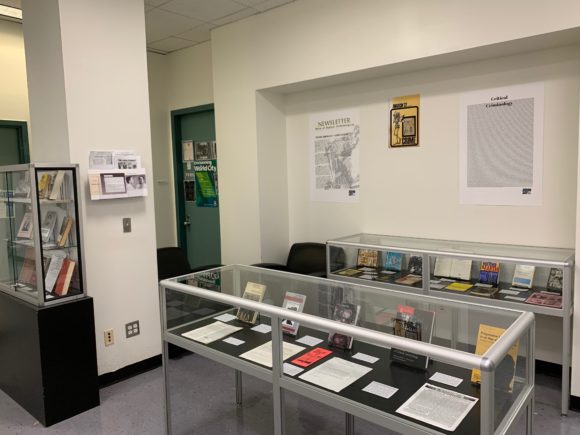

The CSHP isn’t only focused on documenting mass incarceration in NYC. As the Vice Chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Critical Criminology and Social Justice Division, as well as the archivist, Mooney has been accumulating archival information related to the division and the field’s history of activism. The CSHP’s Preserving Justice component, jointly directed by Mooney and Visiting Scholar Albert de la Tierra, has created an exhibition in the Sociology Department displaying some of the core critical criminology texts. It’s open to any students, faculty or staff who are interested in the history of the field and the work of its important thinkers.

Expanding Research Horizons

Mooney is proud to talk about her team of dedicated researchers, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students. With the help of their diverse experiences and interests, the Critical Social History Project is expanding its remit, from the history of Rikers Island to topics including the history of women’s incarceration, other New York carceral institutions including the Tombs and Sing-Sing, mental illness and incarceration, and more. Together, they are showing the persistence of the problems related to the history of mass incarceration, no matter where in history you begin your research—up to and including the present day.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

You can learn more by visiting the Critical and Social History Project’s website.

Recent Comments