Home » Posts tagged 'science'

Tag Archives: science

Back to the Lab with Dr. Jason Rauceo

John Jay College, along with CUNY schools across the city, are moving toward the resumption of on-campus life. Classes are attended in-person, events are being planned, and professors and students alike are headed back into the laboratory. I talked to one of John Jay’s professors in the Department of Sciences, Dr. Jason Rauceo, to find out what it’s been like closing down and reopening his lab.

Dr. Rauceo is an Associate Professor of Biology whose research focuses on the major fungal pathogen Candida albicans. He is also the Director of the Cell and Molecular Biology major at John Jay. In 2021, Dr. Rauceo received a four-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the role of the mitochondrion in C. albicans’ ability to infect hosts and cause disease.

What was it like to get back to lab work after a significant time away during the early part of the pandemic? Did you have to change any protocols or make adjustments to your operating procedures?

Right before CUNY closed in March 2020, I shut the lab down with the expectation that I would not return for 6-12 months. I returned to campus in September 2020, and the major challenge was reopening the lab myself. Students were not allowed on campus, and I needed to calibrate several instruments that I had limited experience operating. Fortunately, my students were available via Zoom and FaceTime for assistance.

What does a typical day in the lab look like, if there is such a thing?

The day usually begins with a short one-to-one meeting with whomever is scheduled to perform an experiment, in which we mainly discuss logistics. Throughout the day, I periodically check in to assist and address any experimental issues if needed. At the end of the day, I inspect the lab to make sure that workspaces are cleaned, all reagents and supplies are properly stored, and all students have left the lab.

What function do students play in your lab?

Students perform the hands-on experimentation and data analysis, and are responsible for general lab maintenance. They also contribute to the development of their projects, which must be directly related to the lab agenda—in this case, C. albicans biology. Students may propose their own experiments for approval after approximately 1.5 to 2 years of experience in the lab.

You place a lot of emphasis on experiential-based learning. What does that mean in practice for your students?

I allow students to test their own hypotheses when safety and costs are not an issue. Also, I allow students to make their own errors during initial training exercises. I found that this approach in lab research builds confidence.

Generally, in the early stages of a new project, a significant amount of time is devoted to optimizing protocols to meet our objectives. During this “optimization phase” of the research, there is an extensive level of troubleshooting required, and a high level of error and ambiguity is observed. I found that a major payoff of experiential-based learning and training is that students propose unique approaches to addressing experimental obstacles.

Your study of SPFH (Stomatin, Prohibitin, Flotillin, HflK/HflC) proteins’ role in mitochondrial function in Candida albicans is being funded by the NIH. It seems that there are some exciting implications for developing antifungal treatments—can you tell me about that?

SPFH proteins are widely conserved in nature and are found in most living organisms. These proteins are important for major biological processes including, but not limited to, respiration, transport, and communication. Candida albicans is a fungus that resides in all humans on mucosal surfaces such as the mouth and gastrointestinal tract in a harmless state. However, changes in our immunity sometimes cause C. albicans infections. Immunocompromised individuals are highly susceptible to C. albicans infections.

Currently, the function of SPFH proteins is limited in C. albicans. We were the first research group to demonstrate that SPFH proteins are required when C. albicans is challenged with environmental stress. Our current proposal seeks to define the molecular function of SPFH proteins. We are collaborating with several prominent research groups in fungal biology and medicinal chemistry to determine the function of the SPFH proteins in mitochondrial function.

One of our project aims is to understand the effects of treating C. albicans with natural compounds that target SPFH proteins. Our initial findings are promising and may be useful in developing novel antifungal strategies.

The NIH award provided me with the funds to expand my lab operations, and I’ve recruited three new undergraduate students; therefore, I will be spending much of the next semester in student training and performing experiments.

Nathan Lents is sticking to the science

As an evolutionary biologist, and author of such books as Not So Different: Finding Human Nature in Animals and Human Errors: A Panorama of Our Glitches, From Pointless Bones to Broken Genes, Nathan H. Lents has joined the ranks of scientists whose work is under attack by proponents of intelligent design.

There is no coherent theory about intelligent design; according to Lents, the one commonality is that supporters “don’t buy modern evolutionary theory, or some part of modern evolutionary theory. They hold a whole variety of incompatible positions.” The views of intelligent design supporters range from believing the planet was created less than 10,000 years ago, to finding a role for God in gradual or ongoing acts of creation and evolution, to those who think God “set up” for life to evolve as it has in something Lents calls “the Perfect Pool Shot.”

Lents’s most recent book, Human Errors, came out in 2018 to great excitement from the science and reading communities. When it was published, he thought that intelligent design supporters “would just roll their eyes. I didn’t offer it as a serious critique [of intelligent design], so I didn’t think they would respond in a serious way but they absolutely did; they went on the attack.” Lents said it took him months to learn about the different types of creationists and how to respond to and refute their attacks effectively, promoting scientific thought without getting dragged into the mud.

This month, Lents and two co-authors can be found standing up for modern evolutionary theory in Science, a journal that has been at the center of important scientific discovery and thought since its founding in 1880, reviewing Darwin Devolves, a new book by biochemist Michael Behe. He is among the best-known figures in the intelligent design movement; Lents characterizes Behe as a serious man who views his own work as serious science.

“Michael Behe believes in common descent, the true age of the earth, that all living things have evolved, he believes in all of that. But the only thing that he takes issue with is the source of all this diversity in life, that then gets acted on by natural selection. He thinks that God or a supernatural force of some kind has to provide this new influx of genetic information somehow, periodically, and then evolution can play out for a while. Either it was preloaded in the ‘perfect pool shot’ or there are ‘continuing miracles of life.'”

While creationism and trying to explain science with a creationist mindset have always been with us, in the late 1990s Behe introduced a concept called “irreducible complexity,” and this notion has really taken over those who are trying to marry science and creationism. Irreducible complexity is the idea that evolution must be false because natural selection acts by propagating mutations that create advantage for the organism; however, some structures are so complex that they never could have evolved, because their individual pieces must work together to convey advantage. Behe holds that evolution could not have produced all of the interrelated structures in a complex system like, for example, the eye, because the innumerable steps and parts it takes to make up the eye (and therefore to create vision) aren’t advantageous on their own, and therefore could not have evolved without the hand of an intelligent designer.

Lents doesn’t agree with that theory. “What we do know is that these structures don’t evolve as fully-formed units. When the eye was evolving, it wasn’t like a fully-formed retina — boom — just appeared, and then a full-formed lens, that’s not how it works. The whole thing becomes gradually more complex, and then, of course, many, many steps later it looks like if you remove any one part the whole thing doesn’t work, but that’s because it’s evolving as a unit, not stepwise. It’s not like building a car. The good thing is that, if you look at the eye, we can find intermediates, not in the fossil record but in living things right now, that have an earlier version of the eye.”

In this review, Lents sticks to the science. They point to sections or examples in Darwin Devolves that fail to take into account evidence produced by testing modern evolutionary theory. Although Lents and both of his co-authors have been subject to attacks on their work by supporters of creationism, he says he’s learned his lesson about responding to attacks that are ultimately unserious or political in nature.

“I’ve come to realize, Lents says, “that in these exchanges, my real audience is not the intelligent design community. I’m writing for millions of silent readers who come into this debate innocently and earnestly when they see their children start to learn about evolution in middle school and they want to see what’s out there, they want to read for themselves. So that’s who I’m writing for, the people who are just genuinely trying to find answers about what the science really says, what evidence do we really have, that kind of stuff. So I’m not really speaking to the intelligent design community anymore, I’m just speaking to the general public, trying to correct the record on science.”

In fact, that really sums up Lents’s approach to writing more generally. He wrote his second book for the general public, “first of all to entertain, but also to help them understand how these little quirks that we have in our bodies have come to be, and how to live with them, and survive and thrive.” It’s very important to Lents to advance the idea of a scientific mindset, which he says intelligent design proponents don’t have.

“Science, at its best, comes at the evidence and tries to come up with an explanation that best fits that evidence. And even when that explanation starts to become what we call accepted science, it is still tested. But intelligent design supporters, including Michael Behe, their starting point is that they have a truth that they already believe is true, and then they try to mold an explanation for the science around that preconceived notion. So it’s backwards. And that’s why they end up with egg on their face so often, because they’ll come up with an explanation that fits the limited data that we have at one point in time, and then we just get more data and a fuller understanding and they have to keep revising their explanation. And that’s just not a good way to come up with the truth.”

Lents plans to continue writing fact-based science texts with the general public in mind, even if he does invite further criticisms from the intelligent design community or other conservative elements. He says he’s currently laying the foundation for his next book, “which is about human sexuality in the evolutionary context. If you see a pattern in my work, it’s that I’m getting more and more controversial with each book.” Lents wants to look at human sexuality as it’s connected to the greater natural world, and the ways that social constructs have shaped our expressions of sexuality. His argument? “A label-free approach to sexuality is much more in line with our natural biology. The only thing labels do is create restrictions.”

Dr. Nathan H. Lents is a Professor of Biology at John Jay College, as well as the Director of John Jay’s Honors College. Apart from being the author of the two books mentioned above, Dr. Lents blogs at The Human Evolution Blog and on Psychology Today. For more, read his bio.

To read his review with co-authors Joshua Swamidass and Richard Lenski in Science, visit the website.

Fostering Success in STEM – Dr. Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín

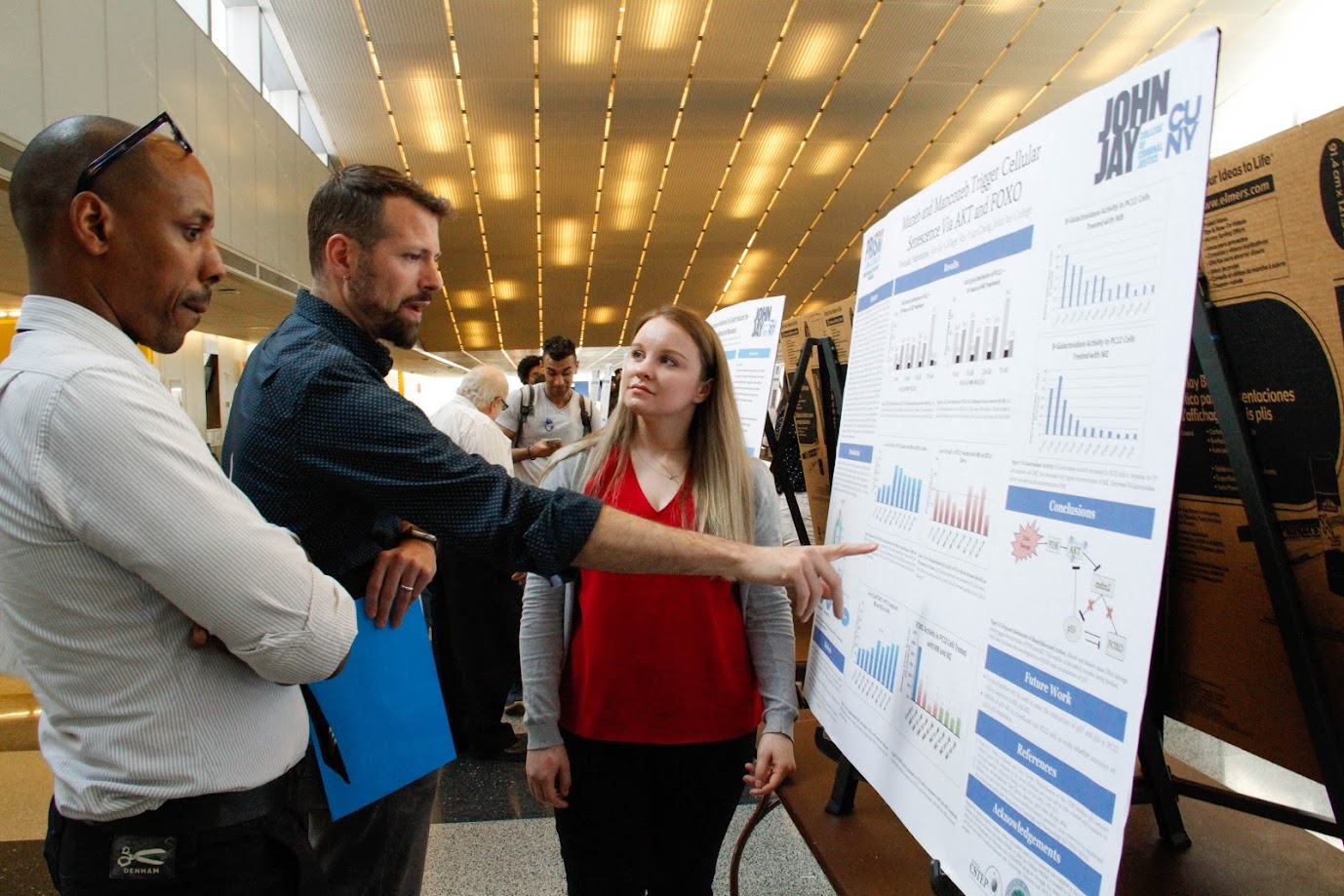

Dr. Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín sees himself in the PRISM students he works with. He credits his alma mater, the University of Puerto Rico, with instilling in him the spirit of preparedness that he brings to student researchers and presenters at John Jay — being ready not only with the technical facts but with the message about why your research is important, and how you are changing the world.

Dr. Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín sees himself in the PRISM students he works with. He credits his alma mater, the University of Puerto Rico, with instilling in him the spirit of preparedness that he brings to student researchers and presenters at John Jay — being ready not only with the technical facts but with the message about why your research is important, and how you are changing the world.

“Because of that, every time we go to a conference, we get minimum one award — my top is three!” he says. “Every time we go to an undergraduate research conference, John Jay’s name always comes up.” It is this tangible commitment to bringing out the best in John Jay’s science students that earned Dr. Sanabria-Valentín, who is the Associate Director of the John Jay Program for Research Initiatives in Science and Math (PRISM), a 2018 APACS President’s Award.

At its heart, PRISM is about teaching students skills, not only in the sciences but also to prepare them to succeed in and after college. “The bread and butter upon which PRISM was founded” is the Undergraduate Research Program. The program provides students with opportunities to be exposed to the process of science beyond their normal classroom studies by working directly with a faculty mentor on an original STEM research project.

And PRISM has grown. A second component is the Junior Scholars program, giving academic support to eligible students that can include stipends, professional development events and supplementary advisement, as well as financial support in applying to post-graduate programs in New York State-licensed professions. Just as important for an institution that counts many first-generation college students among its student body, Junior Scholars collaborates with student support services across the college, like the Math and Sciences Research Center, Center for Career and Professional Development, Wellness Center, Center for Postgraduate Opportunities, and even more. The program is designed to make sure that students have all the tools to get to know their college and excel.

External funding is part of what drives PRISM’s growth. The New York State Collegiate Science and Technology Entry Program, or CSTEP, awards grants to postsecondary and professional schools to start academic support programs — like PRISM — for students from underrepresented minority groups, or who are economically disadvantaged, to help them get into STEM fields. John Jay was among the first class of schools to receive CSTEP funding, thirty years ago and out of roughly 200 PRISM students, the CSTEP grant supports 140. Edgardo’s goal is to double that number over the next five years.

His hard work is a large part of why the CSTEP program is at John Jay — after a short hiatus, Edgardo’s application brought the program back in 2015 — and of John Jay’s unique status as the only school to have institutionalized this type of academic STEM-focused support initiative. He is also responsible for collaborating with other CSTEP schools in the region: NYU, Hostos Community College, Fordham, City College and Mt. Sinai are among the Manhattan and Bronx institutions that participate with John Jay in our CSTEP Regional Research Expos. Participating students are invited to present their own research in poster sessions and attend professional development activities.

His work on and logistical support for the expos has earned Edgardo an award from the President of the Association of Program Administrators for CSTEP and STEP (APACS). The honor also recognizes his success in running a program that benefits students in the sciences. The advisement services offered by PRISM have created the conditions for increased student success at John Jay and degree completion, and the program puts students on a path toward the pursuit of higher degrees, or toward a place in the workforce in a variety of science, technology and computer science fields. The Undergraduate Research Program has measurably helped students to pursue post-graduate degrees in science, medicine and more.

The bottom line for Edgardo, though, is his students. “My kids blow me away every time,” he gushes. “I have complete pride in showing them off at every conference I go to. I have learned so much by helping them with posters and advising on their projects; it’s encouraging that I sometimes find my students to be smarter than me.”

Learn more about:

PRISM: http://prismatjjay.org/

APACS: http://www.apacs.org/

CSTEP in New York State: http://www.highered.nysed.gov/kiap/colldev/CollegiateScienceandTechnologyEntryProgram.htm

Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín, Ph.D. is the Associate Program Director for PRISM and also the Pre-Health Careers Advisor at John Jay. He holds a Ph.D. from NYU-School of Medicine, where his dissertation work involved studying the mechanisms Helicobacter pylori employs to persist in the human stomach for the life span of each host. He came to John Jay after a Post-Doctoral Fellowship at Harvard Medical School followed by 3 years working in the Biotechnology Industry in Boston. Dr. Sanabria-Valentín is the recipient of the ESCMID Young Scientist Award (2007), a Leadership Alliance-Schering Plough Graduate Fellowship (2006), and the NBHS-Frank G. Brooks Award for Excellence in Student Research (2001). He is also a founding member of the NYC-Minority Graduate Student Network and The Leadership Alliance Alumni Association.

Edgardo Sanabria-Valentín, Ph.D. is the Associate Program Director for PRISM and also the Pre-Health Careers Advisor at John Jay. He holds a Ph.D. from NYU-School of Medicine, where his dissertation work involved studying the mechanisms Helicobacter pylori employs to persist in the human stomach for the life span of each host. He came to John Jay after a Post-Doctoral Fellowship at Harvard Medical School followed by 3 years working in the Biotechnology Industry in Boston. Dr. Sanabria-Valentín is the recipient of the ESCMID Young Scientist Award (2007), a Leadership Alliance-Schering Plough Graduate Fellowship (2006), and the NBHS-Frank G. Brooks Award for Excellence in Student Research (2001). He is also a founding member of the NYC-Minority Graduate Student Network and The Leadership Alliance Alumni Association.

Recent Comments