Home » Posts tagged 'sociology'

Tag Archives: sociology

Richard Ocejo – Understanding Small City Gentrifiers

The outbreak of COVID-19 has accelerated a number of existing trends in the United States; along with giving a big boost to remote work and the digital economy, and reinforcing existing socioeconomic inequality, 2020 has also seen the trend of movement from big cities to smaller ones pick up. Whether because larger cities are too expensive or because COVID-19 made them feel not just dense but claustrophobic, residents have reconsidered their environments. While big cities like New York and San Francisco have seen their populations decline over the last five years, some smaller cities – with populations in the tens of thousands rather than the millions – have been seeing an upswing.

Dr. Richard Ocejo, a John Jay professor, sociologist and author, is interested in what it looks like when newcomers arrive in small cities. He’s using Newburgh, New York, a city of about 30,000 in the middle of the Hudson Valley, as a case study, spending time with new and old residents to learn what gentrification looks like in a smaller city. “Newburgh was totally abandoned,” says Ocejo. “Capital had left it, investment had left it, it was just a place to warehouse the poor and struggling. Until New York City became too expensive, then all of a sudden, small, affordable, historic places like Newburgh become valuable again, to a group of people who are looking for these urban lifestyles.”

Gentrifying a Small City

Ocejo sees the characteristics of small-city gentrifiers as distinct from those who have traditionally moved into gentrifying neighborhoods in New York City, like on the Lower East Side or in Brooklyn. People moving to small cities from places like New York are often middle class, mid-career professionals, who are looking to buy property more affordably while still maintaining the lifestyles and habits they developed in the big city. Over the course of several years of field work and interviews, Ocejo has pinpointed some common threads in the narratives Newburgh’s newest residents use to understand their actions.

“They recognize that the reason they left [New York City] was because of being priced out. But when they get to Newburgh, the understanding of what it’s like to not be able to afford a place any more, of having to leave one’s home as a consequence of these larger forces beyond your control, doesn’t resonate in how they understand gentrification as they are perpetuating it in this small city,” says Ocejo. “They don’t see what they’re doing there as gentrifying that will cause this sort of harm that could make somebody leave their home as they had to do. Instead they say, we’ll just do it better.”

Generally, Newburgh’s gentrifiers are opposed to harmful development by “slumlords” or “bad actors;” in contrast, they perceive themselves as providing employment and adding to the tax base. But Ocejo hasn’t seen concrete evidence to back up their narratives. “I don’t know many examples of what we can call a successful gentrification, at least not at any kind of scale,” says Ocejo. “I can’t think of any examples of an equitable integration where there aren’t tensions and conflicts that take place.”

Reckoning with Racism

Ocejo says that some of the challenges he sees playing out in Newburgh are tied into structural racism and the failure of newcomers to acknowledge that they are recreating harmful racial and economic dynamics in Newburgh that caused displacement in New York City. While he observed Newburgh’s newcomers participating in Black Lives Matter protests and marches, he says that the leap to understanding the racist structures that are tied up in gentrification is rarely made. “We don’t talk about gentrification as a racial process,” Ocejo says, “but it is. It’s this extraction of value from racialized spaces, non-white spaces that are taken advantage of through these processes. And that’s not discussed at all.” He says gentrifiers’ inability or unwillingness to confront these issues is exacerbating a key inequality at the heart of the process.

Gentrifying “Better?”

Ocejo does clarify that, although on the whole gentrified spaces tend to end up segregated socially and culturally, there are positives associated with the process. Smaller cities are crying out for even a fraction of the investment New York City has received and, done correctly, municipal revitalization can make a real difference to disadvantaged communities. And in interviews with existing Newburgh residents, he has generally heard people react positively to commercial development in their neighborhoods. However, they aren’t necessarily sure the changes will add up to much real change in their own lives.

“Gentrification is a consequence of much larger forces that are beyond anybody’s control,” says Ocejo. Newburgh’s population of gentrifiers are responding to market forces that are making New York City a difficult place to live long-term without making significant sacrifices or acquiring millions of dollars. But at the end of the day, some groups have the means to make choices about where they will live and whether they will stay or go, while others are unable to make the same choices. It will take structural, policy-based change to make gentrifying urban neighborhoods, and migration in general, more equitable.

Dr. Ocejo has published three papers related to his work in Newburgh and has two additional papers under review. He is also working on the manuscript of a book that will bring together all of his work on this project; he expects it to come out in 2022 or 2023.

Dr. Richard Ocejo is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and the Director of the MA Program in International Migration Studies at the Graduate Center of CUNY. His research, which has been published in a variety of journals including Journal of Urban Affairs, Sociological Perspectives, and more, focuses on cities, culture and work. He uses primarily qualitative methods in his scholarship. Dr. Ocejo is the author of two books: Masters of Craft: Old Jobs in the New Urban Economy (2017) – on the transformation of manual labor occupations like butchering and bartending into elite occupations – and Upscaling Downtown: From Bowery Saloons to Cocktail Bars in New York City (2014) – about the influence of commercial operations on gentrification and community institutions in downtown Manhattan.

Dr. Richard Ocejo is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and the Director of the MA Program in International Migration Studies at the Graduate Center of CUNY. His research, which has been published in a variety of journals including Journal of Urban Affairs, Sociological Perspectives, and more, focuses on cities, culture and work. He uses primarily qualitative methods in his scholarship. Dr. Ocejo is the author of two books: Masters of Craft: Old Jobs in the New Urban Economy (2017) – on the transformation of manual labor occupations like butchering and bartending into elite occupations – and Upscaling Downtown: From Bowery Saloons to Cocktail Bars in New York City (2014) – about the influence of commercial operations on gentrification and community institutions in downtown Manhattan.

A Critical History of Incarceration in New York City

Dr. Jayne Mooney is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay and a member of the doctoral faculty of Women’s Studies and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is also a director and founding member of the Critical Social History Project (CSHP), a research initiative and part of John Jay’s Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project that draws on archival material to shed light on the history of incarceration in New York City.

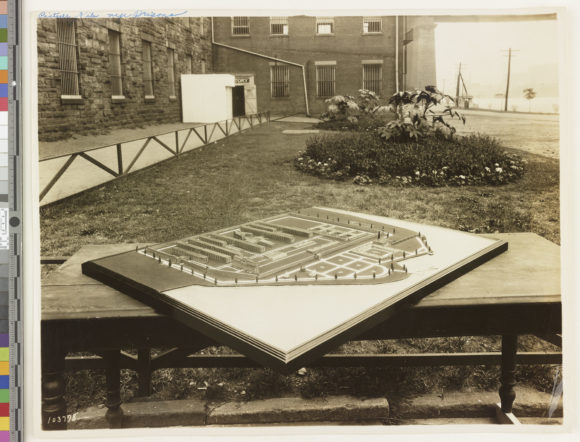

The project began in 2015 with a conversation spurred by reporting on abuse, poor conditions, and a rash of tragedies at Rikers Island; how best, Mooney and colleagues wondered, to preserve the memories of those who had been affected by the infamous jail, including not only the incarcerated but also their friends and families, guards and educators? And so they began the “Other City” project, which forms the largest component of the CSHP. Informed by their research into the history of New York’s penitentiary system, Mooney’s working group is pointing out the problems inherent in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration’s proposal to close Rikers and open four new city jails.

“On the most basic level, what we’re showing is that the current proposals are reinventing the wheel. It’s the same thing that’s always happened. Closing an institution and setting it up again, you’re going to have the same problems, because you’re not getting to those deep-rooted, structural issues,” says Mooney.

Reinventing the Wheel

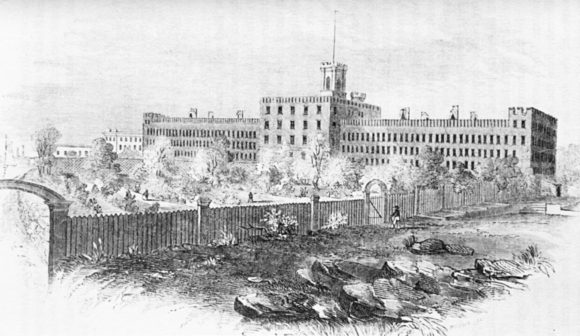

In a forthcoming article, “Rikers Island: The Failure of a ‘Model’ Penitentiary” due to be published in The Prison Journal in 2020, Mooney and her co-author, CUNY graduate student Jarrod Shanahan, go through the instructive failures of incarceration reform in New York City back to the 1735 construction of the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction. They argue that a lack of historical documentation has allowed policymakers to strategically “forget” the failures of past “model” or “state of the art” institutions, continually replacing old jails with new without a look at the larger issues that have led to waves of highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful penal reform.

Set against the backdrop of historical, social and political context, Rikers’ closure and the proposals to replace it look familiar. “All of these places opened in the spirit of optimism—everything was going to change. And then everything goes wrong, these institutions are denounced as embarrassments, and the decision is made to close them down and rebuild. Of course, that’s what’s been happening in the present moment,” Mooney says. She and her colleagues encourage the Mayor’s Office to look beyond the walls of the prison for new solutions to social problems faced by New York and, indeed, the United States.

(Read her December 2019 letter to The Guardian on the subject, “Rikers has failed like others before it, but the solution is not new jails.”)

Preserving Voices, Preserving Justice

Mooney’s challenge to the new proposals is grounded not only in her work in political social history, but also in her background as a critical criminologist. “There’s a very strong abolitionist line all the way through critical criminology,” she notes, which informs the way the Critical Social History Project has approached critiques of the plan to build new jails.

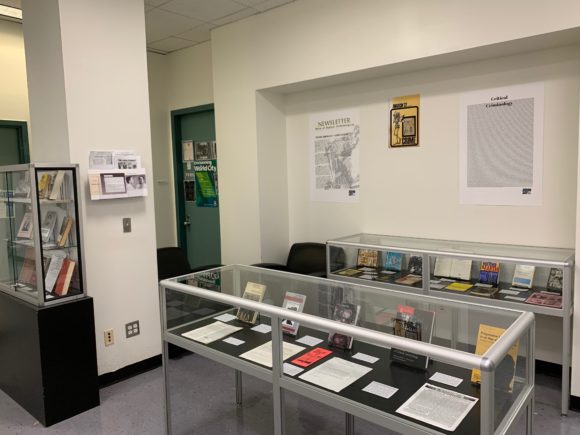

The CSHP isn’t only focused on documenting mass incarceration in NYC. As the Vice Chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Critical Criminology and Social Justice Division, as well as the archivist, Mooney has been accumulating archival information related to the division and the field’s history of activism. The CSHP’s Preserving Justice component, jointly directed by Mooney and Visiting Scholar Albert de la Tierra, has created an exhibition in the Sociology Department displaying some of the core critical criminology texts. It’s open to any students, faculty or staff who are interested in the history of the field and the work of its important thinkers.

Expanding Research Horizons

Mooney is proud to talk about her team of dedicated researchers, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students. With the help of their diverse experiences and interests, the Critical Social History Project is expanding its remit, from the history of Rikers Island to topics including the history of women’s incarceration, other New York carceral institutions including the Tombs and Sing-Sing, mental illness and incarceration, and more. Together, they are showing the persistence of the problems related to the history of mass incarceration, no matter where in history you begin your research—up to and including the present day.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

You can learn more by visiting the Critical and Social History Project’s website.

Social Inclusion Leads to Violence Reduction in Ecuador – Dr. David Brotherton

Since 2007, the Ecuadorian approach to crime control has emphasized policies of social inclusion and innovations in criminal justice and police reform. One notable part of Ecuador’s holistic approach to public security was the decision to legalize a number of street gangs in 2007. The government claimed this decision contributed to the reduction of homicide rates from 15.35 per 100,000 in 2011 to close to 5 per 100,000 in 2017. Professor of Sociology David Brotherton was commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank to spend six months evaluating these claims through a qualitative research project focusing on the impact on violence reduction had by street gangs involved in processes of social inclusion. The results were published in 2018, arguing that social inclusion policies helped to transform gang members’ social capital into a vehicle for behavioral change. In December 2018, Dr. Brotherton was awarded a grant by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation to continue the work.

Since 2007, the Ecuadorian approach to crime control has emphasized policies of social inclusion and innovations in criminal justice and police reform. One notable part of Ecuador’s holistic approach to public security was the decision to legalize a number of street gangs in 2007. The government claimed this decision contributed to the reduction of homicide rates from 15.35 per 100,000 in 2011 to close to 5 per 100,000 in 2017. Professor of Sociology David Brotherton was commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank to spend six months evaluating these claims through a qualitative research project focusing on the impact on violence reduction had by street gangs involved in processes of social inclusion. The results were published in 2018, arguing that social inclusion policies helped to transform gang members’ social capital into a vehicle for behavioral change. In December 2018, Dr. Brotherton was awarded a grant by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation to continue the work.

What did you learn during the initial phase of your research?

We learned a lot. These are very large groups, with over 1,000 members spread across Ecuador, and they managed to create a new kind of culture within their organizations that was pro-social, pro-community, with a strong element of conflict resolution and mediation, cultures where they were working as partners with the government and non-state actors like universities on progressive agendas. They were partners in pro-social activities, everything from creating new youth cultures to voting, job training, and strengthening local communities, all of which you don’t associate with street gangs. And in their ranks are the most marginalized youth of their country, so they can reach kids that are so marginal that other organizations don’t reach them, even indigenous kids from the Amazon, and it is so important to bring them in and work with them. This is all across Ecuador.

When we asked the members what had changed, they said they don’t get into the same level of conflict. Where there might have been a previous period where they were at war with one another, they were able to end it with the government playing a role.

Sometimes these interventions don’t last very long, once the money runs out, but here you had a government that constantly maintained a presence and lived up to its promises, so the trust level became really high.

The end result is not necessarily unique, we’ve seen this in other places like with the Latin Kings in New York and various places in Spain, but the outcome across ten years was quite remarkable. Homicide rates are so indicative of a country’s ability to resolve tension, so when you see the inarguable statistics of homicides going down every year for ten years — it’s related to different factors, they also reformed the police department, but when you see that kind of result it’s pretty impressive.

What key aspects of the inclusion policy allowed gangs to successfully transition from criminal to purely social organizations?

The government recognizes that they won’t change overnight, because the economic situation doesn’t allow that, but you make it such that whatever [gangs] are involved in doesn’t hurt the community, and there are other pathways they can move into and you are creating real opportunities. So what does that look like? It looks like being recruited into programs at the university to give you skills, diploma programs. And these kids become a kind of role model for their mates.

In addition to that, [all of the gangs] were incorporated as non-profit organizations, which allows them to get government grants to do things like community building. You’re not just rhetorically arguing for a new culture, you’re making a new culture and making it happen. Those joining the organization come in with a different set of expectations, and it has a tremendous ripple effect. They created a strata of professional workers.

Also, the police are told not to pick them up, or intervene in their meetings. And the kids don’t fear any kind of stigma, they’re not constantly being harassed. With the communitarian police force, they worked with the heads of the police. It’s a totally unique phenomenon, and flies directly in the face of what we’re pushing in the U.S., which is zero tolerance.

Where else might this social inclusion approach be effective in curbing violence?

I mean, it could be effective in the U.S. Social inclusion is the complete opposite of the repressive policy that nearly always leads to what we call deviant amplification. You need to stop the stigmatization and have meaningful relationships with street groups, with intermediaries from the government. In the U.S., the police are so strong that this is all very difficult.

To make this work anywhere, politically you need to make a decision about where to invest resources. [In Ecuador,] they didn’t invest in the military, they didn’t invest in massive tax breaks for corporations, in fact they did the opposite. They boosted money for culture and art. If you stick with these political decisions, they will pay dividends over time.

What is the next step in completing this research?

I have a full-time field researcher, Rafael Gude, who has been working in Ecuador since April, focusing on the relationship between the Catholic University of Quito and the Latin Kings and Queens. I’m going down myself July 3-15 to do field work both with the Latin Kings and Queens and to attend a big national meeting in Cuenca, then I travel to Las Esmeraldas, on the Pacific coast of Ecuador, where we will interview members of the third major street organization in Ecuador, called Masters of the Street. We want to understand the changes in that group and the roles of social and political empowerment in the reduction in violence.

Las Esmeraldas had the highest rate of violence, with a really high homicide rate of around 70 per 100,000, which is now down to 20, and it’s on the border with Colombia so this is the biggest drug trafficking area and also very poor. This is a completely different socio-economic context, and mainly black Ecuadorians, so we want to see how the whole issue of race works itself out as they’re trying the same policy.

Also, things have changed; although the same party is in power, it’s not the same government. We thought they were going to completely reverse the policy, but a number of media organizations got into this report, and I gave this big talk in Medellín last year, and it’s become a real media story about this success. So this government has maintained the same policy, and embraced it as much or more than the last government.

Right now, we are also looking to do work in the prisons where the inmate population has increased substantially in recent years and many of the incarcerated have joined the groups.

Why is it important to continue this research?

The importance of this work is that it demonstrates a viable alternative to “zero tolerance” and other repressive policies that led to the highest homicide rates in the world — for example, in Central America’s Northern Triangle. The topic has been covered by the BBC and is out in English, Spanish and Portuguese, with multiple other Latin American nations now taking notice, including the president of Mexico.

How does your research dovetail with the HFG Foundation’s mission?

The research meshed with their general focus; they’ve always supported innovative anti-violence or violence prevention studies. For them to come on board, it’s a big deal.

You can learn more about the first stage of this research via the report on the Inter-American Development Bank’s website, or by listening to him talk about his research on the BBC program The Inquiry (starts at 13:43) or on the Peter Collins Show podcast.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College and the CUNY Graduate center. He is the author of a number of books on gangs and immigration, most recently co-authoring Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, and Border Control. He is a founding member of the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime research working group based at the Center on Social Change and Transgressive Studies at John Jay.

CUNY Graduate Center Hosts Press Briefing by Immigration Experts

August 8, 2018 – The Graduate Center of CUNY has the benefit of some of the best immigration scholars in the country. Ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, in which this contentious issue will play (and has already been seen to play) a big role, six distinguished faculty experts on immigration sat down to brief the press on a variety of issues surrounding evolving immigration policy under the Trump administration and related issues, including demographics, economics, and the sociocultural experience of immigrants in the United States.

The panel kicked off with CUNY Graduate Center Distinguished Professor of Sociology Richard Alba, who introduced the idea that immigration policy under President Trump is the most restrictionist and selective this country has seen since the inter-war period of the 1920s. However, he suggested that there are a number of structural constraints on this administration’s ability to push immigration restrictions too far. These include business’s need for new workers, both skilled and unskilled; demographic indicators of an impending dearth of young workers; and a lack of political will even among a Republic Congress to enact major immigration legislation.

Next, David Brotherton, a professor of sociology and criminologist from John Jay College, brought up the idea that the “deportation regime” under Donald Trump is not unique in the history of the United States. He noted earlier examples of deportation- or exclusion-oriented federal policy, including the 1996 Immigrant Responsibility Act, Indian Removal Act, and the 19th century Chinese Exclusion Act. Dr. Brotherton went on to discuss the origins of the Trump Administration’s restrictive immigration policies, particularly the president’s campaign tactics of stoking panic in a segment of the population that feels insecure about their place in society. He emphasized that this strategy represents only the latest in a series of moral panics in American history, calling back to the War on Drugs and earlier rhetoric about the dangers of young black and Latino men.

Dr. Brotherton described U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as arguably the “largest police force in the United States.” ICE’s detention and deportation of immigrants is retroactively punishing many non-native Americans for crimes in their pasts; because these individuals have since put down roots in the country, with families, jobs and wider communities that are hurt when they are suddenly taken away, the policy is cruel. For this reason, Dr. Brotherton has acted as an expert witness since 2007, testifying to the effects of deportation on the individuals detained, their communities, and even their representation.

A second immigration project that Dr. Brotherton is currently engaged in is “Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime,” in which he collaborates with Graduate Center faculty to treat New York City – a sanctuary city, and the only city that guarantees representation to immigrant detainees – as a case study. The project aims to look at this problem from all angles and account for many perspectives.

The next commentator was Margaret Chin, a professor of sociology at Hunter College, who focused on the problem of “glass and bamboo ceilings” that stand in the way of Asian-Americans’ achieving educational equity in New York City. She emphasized the importance of taking race into account when designing programs, such as student tracking and race-conscious admissions.

Nancy Foner, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, is the author of a number of books on immigration. During the briefing, she strove to correct immigration myths that are being spread by the president and members of his administration. First, that immigrants are criminals; in fact, immigrants commit less crime than native-born Americans (excepting immigration infractions), and cities and neighborhoods with higher concentrations of immigrant populations have lower rates of crime that comparable neighborhoods. Second, that today’s immigrant populations aren’t learning English; the “three-generation model” continues to be accurate in describing language-learning patterns in immigrant families. The United States can be called a “graveyard of languages” because immigrants tend to lose their native tongues in favor of English – typically by the third generation, individuals are mostly monolingual in English.

Debunking these myths, according to Dr. Foner, is important to reducing the hostility toward immigrants upon which the administration’s restrictive immigration agenda is predicated. She emphasized that social scientists and journalists alike have a responsibility to help publicize the truth about immigrants and their contributions to society.

According to Philip Kasinitz, a Presidential Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, the underlying strategy of the Trump Administration on immigration is difficult to understand, in that much of the policy is self-contradicting. He noted several key contradictions around the thinking on immigration today. For example, the current moral panic conflating immigrants, illegality and crime comes at a time when crime rates – particularly violent crime – is way down. Americans are also increasingly supportive of immigrants and their participation in society, but increasingly make a distinction between legal and illegal, creating a class of people involved socially, economically and culturally in our society but not politically, a fact that is, in his view, bad for a democratic society. Finally, Dr. Kasinitz talked about the generational factors behind a society that is increasingly diverse, but which at the same time harbors extreme anti-immigrant sentiments.

John Mollenkopf, Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Sociology, also noted contradictions inherent to the views of an older, white segment of the population: their anxiety about allowing immigrants into the country is not in their economic best interests, as many are increasingly dependent on low-wage immigrant labor for their care. As a scholar of the acquisition and use of political power, Dr. Mollenkopf opined that the best way to limit the ability of Republicans in Congress to build a base around anti-immigrant sentiment is to mobilize the increasing numbers of immigrant-origin voters and bring new constituencies into the electorate. In New York City, for example, the majority of the electorate is of immigrant origin, but newer immigrants have not yet organized to develop the same amount of political influence as groups that have been in the United States in large numbers for longer.

The panel wrapped up with questions from the audience. In particular, the discussion touched on the movement to abolish or reform U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an idea that has received some popular attention among Democrats in the lead up to the 2018 midterm elections. Dr. Brotherton said that “a critical mass of people has disappeared” in Latin American and Central American communities, and immigrants across the country have changed their routines out of fear of the agency. Dr. Kasinitz clarified that, despite popular belief, the number of deportations has not risen; rather, the length of immigrant detentions has grown substantially due to a lack of capacity in immigration courts to process detainees. All agreed that more dramatic action or a greater groundswell of support for reform is needed to signal that ICE’s actions are not acceptable to a majority of Americans.

For more information about the immigration research coming out of the CUNY Graduate Center, please visit the GC Immigration page.

Recent Comments