Home » Posts tagged 'immigration'

Tag Archives: immigration

Critical Sociology At Work Around the Globe – David Brotherton and the Social Change Project

Dr. David Brotherton is in high demand. As founder and director of the Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project, a research project at John Jay, he leads grants that span multiple countries and touch subjects from post-release reintegration to immigration and the deportation pipeline. His long background and expertise in critical criminology and sociology have suited him to lead the varied types of prestigious grants the project obtains. Brotherton says that the work has three key points of overlap: “One part is to be able to transcend the academy, to translate your findings from the theory to what it actually means to people. Second, you’re doing work that immediately has an impact, to understand or respond to a social problem. And the third thing is to work with the underrepresented, the marginalized, and to help develop knowledge that goes back to them, to empower them.”

With a mission statement like that, how could the Social Change Project not have ended up at John Jay College? Founded in 2017, the organization almost lived at the CUNY Graduate Center; however, a set of happy accidents brought it to John Jay, where, co-directed by Brotherton and Professor of Sociology Dr. Jayne Mooney, it has been funded every year. Under the project’s umbrella live two working groups: the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime, a working group that focuses on “crimmigration” and the dynamics of border control and migrant detention, and the Critical Social History Project, which features Mooney’s work chronicling the history of incarceration in New York. Today, the Social Change Project is doing work with ramifications that will be felt all over the globe.

The Deportation Pipeline

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

Growing up in a working class London neighborhood, Brotherton has always been interested in the day-to-day conditions and labelling faced by people just trying to get by. His first career in youth organizing and present career in sociology and criminology have a focus in common: applying knowledge to empower the disadvantaged. His background led him to research gangs and incarceration, which brought him to the place he is in today.

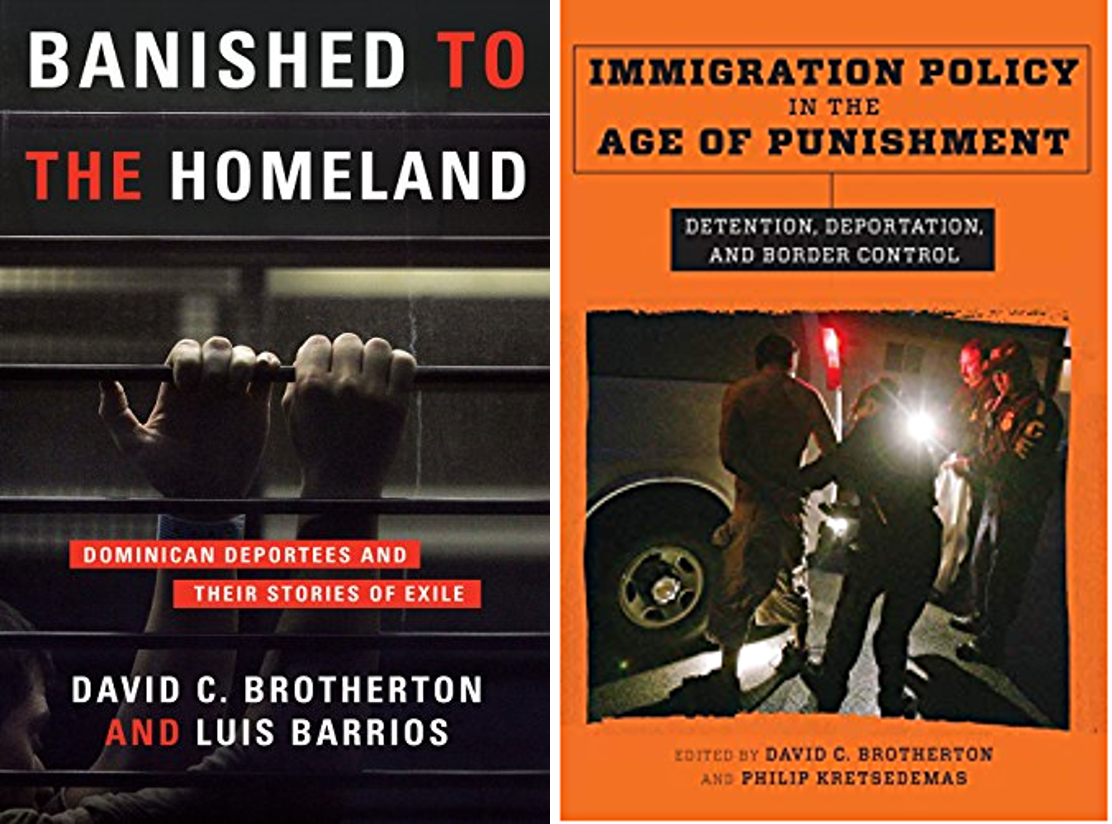

As he tells the story, Brotherton’s work with infamous gang organization the Latin Kings in New York brought him to the Dominican Republic in the early 2000s, where he was giving a talk on his project. “People didn’t want to know about the gangs, all they wanted to know was, why are you sending them all back here?” says Brotherton. “And I said, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll find out.’” That was the start of his investigations into transnational gangs and the issue of deportation, which at the time was not well-studied. That work has led to multiple grants and studies, books including Banished to the Homeland: Dominican Deportees and Their Stories of Exile and Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, Border Control, and the evolution of the multinational TRANSGANG project in Europe, which he advises.

This spring, Brotherton’s project will be working with personnel from Rutgers, including John Jay College graduate Sarah Tosh, to kick off the Deportation Pipeline Project, funded by the National Science Foundation. The team will interview a variety of subjects – immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, including some who have been detained for deportation hearings; lawyers; judges; and even ICE agents if possible – to understand the racialized “deportation pipeline” that runs through NYC back to the Caribbean, and the current situation these communities are living through under the Biden Administration.

“We need to understand all this, and then we’re going to be looking at all the texts that come down, the sanctions, all the laws. We know that Biden has said we’re going after criminal agents and gang members, which is just carrying on from Trump, but I thought we were supposed to have a new, more humane approach. So is it new wine in old bottles or are we going to get a real change in behavior? I don’t know.”

The two-year study will culminate in a book on the topic, as well as a conference with representatives from other municipalities. But Brotherton is already looking past the conclusion of the research to a potential comparative study in another large city or small town, to understand the dynamics of deportation in other American environments with similar demographics being targeted by immigration officials.

Critical Gang Studies

The Social Change Project is also looking forward to wrapping up several projects in the coming months. Since 2019, Brotherton has been consulting for the World Bank in El Salvador, developing national strategies for rehabilitation and reinsertion programs for formerly-incarcerated gang members in that country, which has the second-highest rate of imprisonment in the world after the United States. In April the project published a paper summarizing those findings, and expanding on them. “As we were writing this, we realized there is no real program for rehabilitation anywhere in Latin America, no probation, nothing like that,” says Brotherton. “Once you come out of prison, you’re on your own. So what we’re developing for El Salvador is really a model for the whole of Latin America.”

And July will see the publication of an edited volume, the Routledge International Handbook of Critical Gang Studies, which Brotherton edited along with Rafael Jose Gude, a Research Fellow at the Social Change Project. The book, which includes chapters by a number of CUNY faculty and graduates, will offer new perspectives on gang studies, placing them in the context of their political and social environments. According to Brotherton, it will cover perhaps 18 different countries and will be the largest handbook Routledge has ever released at nearly 900 pages long.

Incarceration and the Credible Messengers

Finally, Brotherton is working on a book on the Credible Messenger phenomenon, due out in 2022. The book, titled What’s Love Got To Do With It?: Credible Messengers and the Power of Transformative Mentoring, begins with a history of the now-widespread program, which recruits the formerly-incarcerated to intervene with young, at-risk kids from their neighborhoods, to keep them away from involvement with the criminal legal system. The book also incorporates qualitative research, including interviews with Messengers, kids, and administrators, as well as the currently incarcerated.

The Social Change Project and Brotherton himself are juggling many projects, each with many moving parts. But Brotherton relies on the connections he’s made over his career teaching at both John Jay and the CUNY Graduate Center, and doing research around the world, to keep the plates spinning. “It’s difficult,” he says. “Sometimes it gets overwhelming, but I always try to make sure I’ve got really good people in each project.”

At the end of the day, Brotherton is proud to be doing work that makes a difference for underserved, understudied communities that can face immense challenges. “I think the project carries on a rich tradition at John Jay. We’re following that tradition of socially conscious, critical social science.”

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and of Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. His research focuses on gangs and globalization, immigration, and deportation and border control. He is the author of numerous books and articles, and has received grants from a variety of public and private agencies.

Podcasting at John Jay: Making Research Accessible

If you’re like us, you love podcasts enough that you’ve subscribed to more than you can listen to in a week of subway commutes. Podcasting, then called online radio, rose in popularity with the proliferation of mp3 players in the early 2000s. In tandem with other personal platforms like blogs, podcasts exemplified the “democratizing spirit” of the internet.

Today, they are big business. Since the release of Serial in 2014, podcasts have boomed. Monthly listeners have nearly doubled since 2014, from around 39 million Americans to an estimated 90 million. As the listening audience grows, quality improves, and bigger names get interested in the medium, advertisers are investing millions.

At John Jay, interest in podcasting has risen along with the medium’s growing potential. The college is home to a variety of podcasts, run by students, faculty and staff, on a rainbow of topics. For example, students in the English department work with Professor Christen Madrazo to write, produce, and edit Life Out Loud, which highlights the diverse voices and real stories of John Jay’s student body. We also have faculty working on podcasts hosted outside John Jay, podcasts run by research centers, and faculty and staff who produce their own shows, right here on campus.

We will introduce you to two homegrown John Jay podcasts that seek to translate scholarship into a form that everyone can understand. Meet Kathleen Collins, a Reference Librarian and Professor at John Jay College, and Nick Rodrigo, a CUNY Ph.D. candidate and John Jay College adjunct professor. While Kathleen is on her 38th episode of podcast Indoor Voices, and Nick has just released the first six episodes of They Are Just Deportees, both share the desire to take CUNY research out of the ivory tower and bring it to the community.

Kathleen Collins has been producing Indoor Voices since the summer of 2017. She started the podcast as “a way to highlight the fascinating things going on around CUNY that might not be widely known. There are so many inhabitants in the CUNYverse doing incredibly interesting things… We like being able to provide a low-stakes, easy-to-share platform for people to talk about their work.”

Kathleen Collins has been producing Indoor Voices since the summer of 2017. She started the podcast as “a way to highlight the fascinating things going on around CUNY that might not be widely known. There are so many inhabitants in the CUNYverse doing incredibly interesting things… We like being able to provide a low-stakes, easy-to-share platform for people to talk about their work.”

To Kathleen, the conversations are the key element. She and her co-host, La Guardia Community College librarian Steven Ovadia, interview CUNY faculty, students, alumni and staff members about their research or creative output; they have a great deal of leeway to highlight what interests them.

Nick Rodrigo is new to podcasting, overcoming challenges as he meets them in the course of creating They Are Just Deportees. The newly-launched show examines the various ways in which the U.S. immigration enforcement system shapes and controls the lives of migrant communities in this country. With co-host Darializa Avila Chevalier, TAJD helps listeners to understand “the multiple sites of border enforcement in the U.S., and the punitive effects of the country’s periodic moral panics on the ‘criminal alien.'”

Nick Rodrigo is new to podcasting, overcoming challenges as he meets them in the course of creating They Are Just Deportees. The newly-launched show examines the various ways in which the U.S. immigration enforcement system shapes and controls the lives of migrant communities in this country. With co-host Darializa Avila Chevalier, TAJD helps listeners to understand “the multiple sites of border enforcement in the U.S., and the punitive effects of the country’s periodic moral panics on the ‘criminal alien.'”

Nick, and his associates in the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime Working Group (the sponsor of the podcast), think this is a particularly relevant topic. “Immigrant rights have come under increasing threat from the state, with bans on immigration from Muslim majority countries, the detention of children at the U.S./Mexico border, and the pledge of this administration to increase the forced removal of all undocumented people. … It is vitally important that the deportation system — which expels up to 300,000 persons a year — be placed in the historical context of this country’s treatment of the ‘other,’ while focusing on the real time implications of the current system on immigrant communities.”

For both showrunners, podcasting is a great way to make sometimes-complex issues and scholarship more accessible to an average listener. Says Nick, “two of the major issues in scholarship today are the ‘ivory tower’ mentality of academics and a lack of interdisciplinary focus on major social issues. Conferences and public lectures can be delivered in such inaccessible language that they can be alienating to non-academics. Podcasting allows for the complex issues concerning immigration enforcement to be distilled and presented to the public in a way that is accessible and digestible, with the opportunity for the listener to pause, reflect, and reengage at their own pace. Podcasting also provides a platform for criminologists, sociologists, public health experts, geographers, and journalists to come together on an issue and, if the interview structure is good, a compelling narrative for change can be constructed.”

Kathleen also wants to make it easier for non-experts to engage with what CUNY produces. “There is so much going on within CUNY,” she says, “and it shouldn’t be hidden inside the academy. Podcasts are a good way to get people interested in new things — it’s a mini, portable seminar for your ears. But since Steve and I act as generalists in our role as interviewers, we can hopefully elicit a layman’s interpretation of what scholars are thinking and writing about. The point is to bring attention to the author or artist, and ask about their research and writing process and teaching — these topics bring the conversation to a universal level.”

Creating content to fit the platform can sometimes be challenging. Nick was “forced to learn new skills on the job,” but found that his struggles with editing gradually turned into confidence! Kathleen cites the extensive support and inspiration from other podcasters and staff at the college as a source of her success and joy in creating Indoor Voices.

In the end, she says she loves every episode she produces — thanks to the satisfying conversations and intimate connections she can form with guests during a 40 minute interview, each new episode supplants the last as her new favorite.

Check out the latest episodes of Indoor Voices, They Are Just Deportees, and more John Jay podcasts:

- Indoor Voices: J Journal founders Adam Berlin and Jeffrey Heiman have been producing the literary magazine for twelve years. The high quality creative work they feature deals with contemporary justice issues, but not always in a way you might expect.

- They Are Just Deportees: You can find the first six episodes on the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime website, or by searching on Spotify.

- Reentry Radio: The latest episode of the podcast produced by John Jay’s Prisoner Reentry Institute deals with employment discrimination against justice-involved individuals, with special guest Melissa Ader of the Legal Aid Society’s Worker Justice Project.

- This World of Humans: Host Nathan Lents talks to Hunter College researcher Dr. Jill Bargonetti about using mouse models to study triple-negative breast cancer.

A Legacy of Violence: Impact Magazine 2018-19

In American politics, issues like immigration and the refugee crisis generate national headlines daily. But the complex dynamics of immigration are inextricably tied to U.S. history in the Americas, where a legacy of colonialism continues to define the relationship between the United States and the nations of Central and South America.

More than 50 years of interventions in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Panama, Chile, Brazil and other countries in the southern hemisphere have affected the lives of these countries’ residents in various ways. Many have resulted over the long term in the systematic destabilization of government coupled with a legacy of violence and military dictatorship, contributing to the reasons that immigrants may cite for wanting or needing to leave their homelands: gang violence, repression, dictatorship and more.

Several professors and students at John Jay have made it their life’s work to investigate the causes and ramifications of this instability, among them José Luis Morín, Claudia Calirman, Pamela Ruiz, and Marcia Esparza. We profiled these scholars in our latest issue of Impact magazine. Read on for a summary of our Impact feature story.

Suing for Justice

José Luis Morín, Chair of John Jay’s Latin American and Latinx Studies Department, is deeply involved with the process of finding justice for the victims of the American 1989 invasion of Panama. Morín had been in the thick of the invasion, which he recalls as “literally a war zone,” and subsequently filed a lawsuit on behalf of individuals who had been directly harmed, seeking reparations from the United States.

José Luis Morín, Chair of John Jay’s Latin American and Latinx Studies Department, is deeply involved with the process of finding justice for the victims of the American 1989 invasion of Panama. Morín had been in the thick of the invasion, which he recalls as “literally a war zone,” and subsequently filed a lawsuit on behalf of individuals who had been directly harmed, seeking reparations from the United States.

Nearly 30 years later, in December 2018, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights finally issued a decision in the case, holding the U.S. government solely responsible for the deaths of Panamanian citizens during the invasion; it is responsible for compensating the victims for damages.

Finally having a decision saying that the U.S. had violated human rights through its actions was a key step toward justice. Morín returned to Panama following the decision, going to communities to explain what this meant and speak to the individuals and families who were part of the case.

“What makes this particularly relevant, and so critical to the work we do in this department, is having our students learn about the history of Latin America and how the U.S. played such an integral role in how these countries developed,” said Morín.

Art Under Fire

The U.S. justified its intervention in Panama as a defense of democracy, but some U.S.-backed “democratic” leaders have turned out to be authoritarian dictators. This was the case in Brazil, where a right-wing authoritarian government ruled from 1964 to 1985.

Claudia Calirman, Associate Professor of Art & Music, is an expert on artistic resistance to government repression in Brazil, and her research — including her first book, Brazilian Art Under Dictatorship — explores how art was expressed in mediums designed to thwart detection. These mediums include body art and what was called “ready mades,” which are every day objects modified to carry subversive or critical messages that could be circulated publicly without implicating the artist.

Claudia Calirman, Associate Professor of Art & Music, is an expert on artistic resistance to government repression in Brazil, and her research — including her first book, Brazilian Art Under Dictatorship — explores how art was expressed in mediums designed to thwart detection. These mediums include body art and what was called “ready mades,” which are every day objects modified to carry subversive or critical messages that could be circulated publicly without implicating the artist.

Calirman’s ongoing work explores different facets of Brazilian art over a variety of time periods, showcasing the ways Brazilian artists approach tough issues and combat repression. Her forthcoming book deals with Brazilian women’s struggles with the term “feminism” as it has applied to their work since the 1960s and ’70s. And Calirman is working on curating a Spring 2020 exhibit at John Jay’s Shiva Gallery about ongoing censorship of art in Brazil.

periods, showcasing the ways Brazilian artists approach tough issues and combat repression. Her forthcoming book deals with Brazilian women’s struggles with the term “feminism” as it has applied to their work since the 1960s and ’70s. And Calirman is working on curating a Spring 2020 exhibit at John Jay’s Shiva Gallery about ongoing censorship of art in Brazil.

Uncovering Violence

Pamela Ruiz is a recent graduate of the CUNY Criminal  Justice doctoral program whose dissertation analyzed the evolution of gang violence in the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. An explosion of gang violence in these Central American countries is connected to instability and the destabilization of democratic governments.

Justice doctoral program whose dissertation analyzed the evolution of gang violence in the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. An explosion of gang violence in these Central American countries is connected to instability and the destabilization of democratic governments.

Ruiz aimed to classify violence that is truly gang-associated, to dispel myths around violence and better target enforcement. “The perception is that all this violence is attributed to gangs,” she explained, ‘but when you go into a country and interview people, you discover that it’s different groups contributing to violence in different areas.”

Her quantitative methods are filling a key gap in research in the region, providing reliable data that policymakers can use to reduce violence, target corruption, and more.

Documenting Dictatorship

Marcia Esparza, Associate Professor of Sociology and an expert on genocide, state crimes, and human rights violations, would argue that, wherever violence and repression are to be found, remembering victims and commemorating resistance is vital in learning from the past and addressing present violence and corruption.

“If we don’t look at the long-term footprints of militarization on the local level, we cannot talk about democracy or democratic institutions,” she says. Esparza was inspired by her work interviewing genocide survivors in Guatemala to found the Historical Memory Project, which archives and draws on primary sources to memorialize the victims of genocide and state violence, and those who resisted it.

She also emphasizes the importance of helping John Jay students connect with their histories as part of a diaspora. Esparza’s students play a key role in the project’s efforts, as they organize and sort through the large archive to pull together educational exhibitions.

Shared History

The shared history of interventionist foreign policy and authoritarian rule has created a spider’s web of mutual entanglements that continue to tie the United States to its southern neighbors to this day. This long-term history of invasion and intervention by the United States has created patterns and threads that John Jay scholars trace in their efforts to understand, alleviate, and memorialize violence and instability in these countries, in order to achieve justice, create a lasting peace and, in the process, help some Latinx John Jay students better understand their own histories.

For the full feature, please visit the John Jay Faculty and Staff Research page to read the whole magazine in PDF form!

CUNY Graduate Center Hosts Press Briefing by Immigration Experts

August 8, 2018 – The Graduate Center of CUNY has the benefit of some of the best immigration scholars in the country. Ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, in which this contentious issue will play (and has already been seen to play) a big role, six distinguished faculty experts on immigration sat down to brief the press on a variety of issues surrounding evolving immigration policy under the Trump administration and related issues, including demographics, economics, and the sociocultural experience of immigrants in the United States.

The panel kicked off with CUNY Graduate Center Distinguished Professor of Sociology Richard Alba, who introduced the idea that immigration policy under President Trump is the most restrictionist and selective this country has seen since the inter-war period of the 1920s. However, he suggested that there are a number of structural constraints on this administration’s ability to push immigration restrictions too far. These include business’s need for new workers, both skilled and unskilled; demographic indicators of an impending dearth of young workers; and a lack of political will even among a Republic Congress to enact major immigration legislation.

Next, David Brotherton, a professor of sociology and criminologist from John Jay College, brought up the idea that the “deportation regime” under Donald Trump is not unique in the history of the United States. He noted earlier examples of deportation- or exclusion-oriented federal policy, including the 1996 Immigrant Responsibility Act, Indian Removal Act, and the 19th century Chinese Exclusion Act. Dr. Brotherton went on to discuss the origins of the Trump Administration’s restrictive immigration policies, particularly the president’s campaign tactics of stoking panic in a segment of the population that feels insecure about their place in society. He emphasized that this strategy represents only the latest in a series of moral panics in American history, calling back to the War on Drugs and earlier rhetoric about the dangers of young black and Latino men.

Dr. Brotherton described U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as arguably the “largest police force in the United States.” ICE’s detention and deportation of immigrants is retroactively punishing many non-native Americans for crimes in their pasts; because these individuals have since put down roots in the country, with families, jobs and wider communities that are hurt when they are suddenly taken away, the policy is cruel. For this reason, Dr. Brotherton has acted as an expert witness since 2007, testifying to the effects of deportation on the individuals detained, their communities, and even their representation.

A second immigration project that Dr. Brotherton is currently engaged in is “Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime,” in which he collaborates with Graduate Center faculty to treat New York City – a sanctuary city, and the only city that guarantees representation to immigrant detainees – as a case study. The project aims to look at this problem from all angles and account for many perspectives.

The next commentator was Margaret Chin, a professor of sociology at Hunter College, who focused on the problem of “glass and bamboo ceilings” that stand in the way of Asian-Americans’ achieving educational equity in New York City. She emphasized the importance of taking race into account when designing programs, such as student tracking and race-conscious admissions.

Nancy Foner, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, is the author of a number of books on immigration. During the briefing, she strove to correct immigration myths that are being spread by the president and members of his administration. First, that immigrants are criminals; in fact, immigrants commit less crime than native-born Americans (excepting immigration infractions), and cities and neighborhoods with higher concentrations of immigrant populations have lower rates of crime that comparable neighborhoods. Second, that today’s immigrant populations aren’t learning English; the “three-generation model” continues to be accurate in describing language-learning patterns in immigrant families. The United States can be called a “graveyard of languages” because immigrants tend to lose their native tongues in favor of English – typically by the third generation, individuals are mostly monolingual in English.

Debunking these myths, according to Dr. Foner, is important to reducing the hostility toward immigrants upon which the administration’s restrictive immigration agenda is predicated. She emphasized that social scientists and journalists alike have a responsibility to help publicize the truth about immigrants and their contributions to society.

According to Philip Kasinitz, a Presidential Professor of Sociology at Hunter College, the underlying strategy of the Trump Administration on immigration is difficult to understand, in that much of the policy is self-contradicting. He noted several key contradictions around the thinking on immigration today. For example, the current moral panic conflating immigrants, illegality and crime comes at a time when crime rates – particularly violent crime – is way down. Americans are also increasingly supportive of immigrants and their participation in society, but increasingly make a distinction between legal and illegal, creating a class of people involved socially, economically and culturally in our society but not politically, a fact that is, in his view, bad for a democratic society. Finally, Dr. Kasinitz talked about the generational factors behind a society that is increasingly diverse, but which at the same time harbors extreme anti-immigrant sentiments.

John Mollenkopf, Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Sociology, also noted contradictions inherent to the views of an older, white segment of the population: their anxiety about allowing immigrants into the country is not in their economic best interests, as many are increasingly dependent on low-wage immigrant labor for their care. As a scholar of the acquisition and use of political power, Dr. Mollenkopf opined that the best way to limit the ability of Republicans in Congress to build a base around anti-immigrant sentiment is to mobilize the increasing numbers of immigrant-origin voters and bring new constituencies into the electorate. In New York City, for example, the majority of the electorate is of immigrant origin, but newer immigrants have not yet organized to develop the same amount of political influence as groups that have been in the United States in large numbers for longer.

The panel wrapped up with questions from the audience. In particular, the discussion touched on the movement to abolish or reform U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an idea that has received some popular attention among Democrats in the lead up to the 2018 midterm elections. Dr. Brotherton said that “a critical mass of people has disappeared” in Latin American and Central American communities, and immigrants across the country have changed their routines out of fear of the agency. Dr. Kasinitz clarified that, despite popular belief, the number of deportations has not risen; rather, the length of immigrant detentions has grown substantially due to a lack of capacity in immigration courts to process detainees. All agreed that more dramatic action or a greater groundswell of support for reform is needed to signal that ICE’s actions are not acceptable to a majority of Americans.

For more information about the immigration research coming out of the CUNY Graduate Center, please visit the GC Immigration page.

John Jay Scholars on the News – Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA and Dreamers)

Hundreds of thousands of immigrants to the United States who arrived as children were protected by the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which allowed them to live, study and work in the country. Shortly after entering office, Donald Trump put a (currently defunct) deadline on phasing out the program and asked Congress to create a permanent solution which has not yet emerged, making these hundreds of thousands of immigrants into a political football and creating extreme anxiety about their futures. Despite professed political will on both sides of the aisle to keep DACA program beneficiaries (often conflated with Dreamers, or supporters of a Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act) in the country, the process of creating a legislative solution to protect these individuals has gotten bogged down amid new debate over levels of legal as well as illegal immigration, discussion of building a wall on the US’s southern border, and related issues. As a case makes its way through the courts, there are currently no signs of progress being made, whether on a short- or long-term solution for Dreamers, or for comprehensive immigration reform more broadly.

The fight over Dreamers is ongoing, thanks to a court order staying the Trump Administration’s directives to terminate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and continuing Congressional inaction toward creating a path to citizenship. What do you think is the ideal fix for Dreamers?

Jamie Longazel (Associate Professor, Political Science): Some may argue that blanket citizenship for Dreamers is not possible, but I’m a firm believer in working to expand the realm of possibility.

Isabel Martinez (Assistant Professor, Department of Latin American and Latina/o Studies): The ideal legislative fix for Dreamers is a pathway to citizenship that is not punitive and takes into account the many years that they have lived in the United States. This means eliminating the conditional permanent resident provisions that have been included in several versions of the “Dream Act” that in some cases mandate thirteen total years before the ability to apply for citizenship; lowering application fees; and widening the ability to regularize status. Better legislation would raise the limit on the age of arrival (now sixteen) and remove the maximum age (currently thirty). It would also include a way for Dreamers’ parents to regularize their statuses, either via sponsorship by Dreamers or other citizen children, or on their own. It is wholly punitive to grant children of immigrants a pathway to citizenship and not their parents.

Dan Stageman (Director of Research Operations, Office for the Advancement of Research): Dreamers are a particularly sympathetic class of immigrants because they fit into the American narrative of meritocratic achievement, and because they were too young to be seen as culpable for the “crime” of their unauthorized presence in the US. In a moral sense, however, they are no more deserving of citizenship than low-wage immigrant workers who underpin significant sectors of the American economy, who pay taxes, and contribute to their communities of residence in countless ways. Perhaps more importantly, Dreamers are connected to this supposedly less deserving segment of the undocumented population through family ties and social bonds. So no legislative fix that focuses narrowly on Dreamers is intrinsically good for them – it is simply seen as more politically possible than a genuinely inclusive and comprehensive approach to legislation.

Part of the problem with making a push toward legislative change is that issues tend to fall out of the news cycle or be supplanted by newer and bigger issues. How can activists keep DACA at the forefront of legislators’ minds and continue to push for change?

Isabel: Immigration activists have been fighting for a Dream Act for sixteen years, but what is hopeful is that we are currently seeing the highest percentages of voters supporting a way for Dreamers to remain in the country legally. Activists and allies must be media and politically savvy and ensure that this support continues and grows, and is continuously broadcast to legislators. This means that DACA activists and allies must be media and politically savvy. Media and legislators must also do the right thing to build further support to get a law passed.

Jamie: I think activists deserve a lot of credit for keeping this conversation going, despite the media’s tendency to get bored and move on. My sense is that, within activist circles and immigrant communities, this issue hasn’t gone away at all, even if the national media has stopped covering it and we have temporarily lost legislators’ attention.

One helpful tactic for activists to consider as they try to build the power necessary to enact meaningful change is issue linking. DACA is about immigration, but it’s also about economic injustice, race, and unequal access to certain rights and privileges. By bringing DACA recipients and other undocumented folks into the conversation on, say, universal healthcare (and vice versa), not only does the issue stay on the agenda, but it also helps to boost cross-issue solidarity where we’d otherwise have activists working in silos.

Dan: What is striking is when you see groups like United We Dream – an undocumented youth grassroots organization – shifting their focus to providing practical support for immigrants facing deportation. It’s an indication that the faith these groups place in the political process to solve their very real and immediate human problems is at a low ebb.

Can you state the case for allowing Dreamers to stay in the United States?

Isabel: Dreamers are already Americans! They have assimilated – the only thing that separates them from other young people is a piece of paper. Removing Dreamers would be removing Americans, as well as much-needed talent and potential in which this country has already invested. Additionally, sending Dreamers back to countries and communities that they do not know and where they do not possess social ties is setting them up for failure. These countries have limited plans to receive and integrate them.

Jamie: I don’t think Dreamers are especially deserving because they are high achieving or assimilated. Claims like these can reinforce notions of “us” versus “them” that have long plagued the immigration debate. I think they are deserving because they are human beings, because no one deserves to live in fear, because no one deserves to be denied access to basic rights. I think Dreamers should be permitted to stay in the United States because it is the right thing to do.

Isabel: The other case is rooted in the United States’ obligations as an imperialist state: the majority of DACA recipients are Mexican, approximately 79%. Their arrivals to the United States coincided with the shocks or aftershocks of economic deals, including NAFTA, made between the US and Mexico that had losers as well as winners, namely many poor Mexican families who could no longer survive due to conditions of the deals. If we look at other countries of origin including the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and El Salvador, we see immigration as the effect of failed or highly lopsided bi-national policies enacted with the United States. This is considered alongside increased border militarization that made the conditions of circular migration deadly and expensive for adult migrants like these young peoples’ parents. The United States has had its hand in the conditions that pushed many families from these communities to enact strategies that let them survive together; as such, the United States has a moral obligation to right these wrongs by receiving and integrating Dreamers and other immigrants.

Dan: I would again broaden the lens to include all “unauthorized permanent residents,” a group that includes any individual who has built the kinds of social and economic ties to the US that are the essential features of establishing long-term community membership, but is unable to legalize their presence. That definition in and of itself makes the case: the ethical framework for community membership goes back at least to Rousseau’s Social Contract, and the mutual obligation it establishes between the individual and their society. Dreamers and other unauthorized permanent residents are fulfilling their end of the social contract through their economic and cultural contributions to American life; unfortunately, the federal government has not reciprocated. Congress passed the last comprehensive immigration law in 1996 – over 20 years ago. The heartbreaking stories that have recently become so common, of individuals deported after 20, 30 or 40 years of US residency, are the direct result of Congress’s historic refusal to address the instability and vulnerability these immigrants have faced throughout their time in the country.

The reality is that vulnerable people are easy to exploit – illegality is, in effect, an informal guest worker program that allows the US economy to benefit from Dreamers and other unauthorized permanent residents without providing for their welfare. This is also why local governments and private prison companies have been able to take increasingly entrepreneurial approaches to their involvement in immigrant detention and deportation. The simple case for a path to citizenship is that these forms of exploitation are morally repugnant and un-American.

What is the best thing others can do to support the Dreamers?

Jamie: If we are talking about folks who are not immigrants, or immigrants who do not have a precarious legal status, then my suggestion would be to stay active – attend rallies, share information, or join an organization. And I think folks should think hard about how our struggles are intertwined. Solidarity is how otherwise powerless groups become powerful. But it is important that Dreamers and other affected immigrants lead the way, because sometimes well-intended actions and words from unaffected people can do more harm than good.

Dan: Give generously to advocacy organizations like the New York Immigration Coalition or the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. Write and call senators and congresspeople in support of DACA legislation. Most importantly, learn about the needs and vulnerabilities of immigrant communities where you live and work, and intervene in whatever way you can.

CUNY has one of the largest populations of Dreamers of any university system in the country, and while it would be irresponsible for any institution to tell these students that we can keep them safe from deportation, we can find other ways to help alleviate the incredible stress they’ve been under since the 2016 election; for example, establishing scholarships and emergency support funds, holding regular legal clinics, providing physical and mental health services, and ensuring the confidentiality of their education data are some of the things that CUNY has taken on to support our Dreamers.

Isabel: Individuals can follow our lead at John Jay for local-level support. For college-going Dreamers, we will be opening an Immigration Student Success Center in the fall that will centralize resources – academic, financial, social and legal – that are essential to their success. This is the culmination of two and a half years of work that focused on creating systems to protect, support, and empower our John Jay Dreamers.

In addition, according to a variety of polls the majority of Americans support a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers. Voters need to turn that passive support into active support and pressure their representatives to vote on a bill ASAP, with calls, emails, visits, op-eds and town hall testimonials that share how important it is that this issue is resolved. This pressure should be placed at all levels of government and in the private sector. Private citizens and corporations can advocate for state and local government to support Dreamers by passing bills that provide in-state tuition, state financial aid, and drivers’ licenses; allow them to obtain professional licenses to practice medicine and law, or teach; and restrict cooperation with DHS and ICE.

Some states and institutions are instituting limited solutions for DACA recipients, like a bill proposed in Rhode Island to allow DACA recipients to obtain drivers licenses and work permits despite expired federal status, or certain universities helping with DACA renewal fees or offering special opportunities for non-citizenship-dependent research and educational opportunities. How helpful do you think these solutions are in mitigating the current circumstances Dreamers find themselves in?

Isabel: These are very helpful, but aren’t enough. In-state tuition and financial aid can mean the difference between DACA recipients enrolling or not in college, and, once enrolled, stopping frequently to save money or paying by semester. And of course, there are significant wage differentials between those with and without college degrees or professional development opportunities. Providing funding for internships and research enables DACA recipients to position themselves to procure better (status and –paying) jobs during school and after graduation.

Dan: While state and local-level solutions are not a replacement for comprehensive federal immigration reform including a path to citizenship, they are absolutely necessary in its absence. Most important among these solutions are the ones that, like California’s recent SB-54, limit law enforcement data sharing and cooperation with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). It’s important for states and localities to announce their intentions to protect their communities from arbitrary detention and deportation, and follow through with legally binding statutes that prevent local law enforcement agencies from contributing to the process in any way.

Jamie: What I appreciate most about measures like this is their symbolic power. These places are leading by example. They’re showing us what inclusion could look like, showing us that they are not afraid, and expanding our collective sense of what is possible.

Does the focus on DACA recipients in the news and policy debate overlook other undocumented immigrants, or ease their own paths toward citizenship? Do you believe this debate will end up helping all undocumented residents?

Dan: I think overall the focus on DACA recipients does a disservice to other undocumented immigrants. It sets up a contrast between the supposedly achievement-oriented, ‘model immigrant’ Dreamers, and their hard-working (but often low-wage) parents and neighbors who are no less deserving. This is a false dichotomy, and not one that anyone who supports immigrant rights should be playing into.

Jamie: I think the focus on DACA recipients has overlooked other undocumented immigrants, but only because of the way the issue has been framed (i.e., depicting DACA recipients as deserving in contrast to other undocumented folks). There are plenty of other ways we can frame the issue that are actually favorable to immigrants across the spectrum of legal statuses.

For instance, I think talking about children who were brought to the United States without authorization can complicate what is otherwise a rather simplistic immigration debate. People talk about “legal” and “illegal” immigration as though there is a binary that is synonymous with “good” and “bad.” But here we see that the reality is far more complicated. DACA also opens up an opportunity to talk about nuances that many non-immigrants are unaware of: mixed-status families and the unique experiences of “1.5 generation” immigrants, to name a couple of examples.

What I’m saying is that so much of our public debate has relied on stereotypes and myths! With DACA, I think we have an opportunity to confront and challenge those myths, but we have to be very careful not to reinforce them.

(Answers may be lightly edited for clarity.)

Dr. Jamie Longazel is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at John Jay College. His research examines issues of race and political economy, typically within the contexts of immigration and imprisonment. His recent book, Undocumented Fears: Immigration and the Politics of Divide and Conquer in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, uses the debate around Hazleton’s controversial Illegal Immigration Relief Act (IIRA) as a case study that reveals the mechanics of contemporary divide and conquer politics and makes an important connection between immigration politics and the perpetuation of racial and economic inequality.

Dr. Jamie Longazel is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at John Jay College. His research examines issues of race and political economy, typically within the contexts of immigration and imprisonment. His recent book, Undocumented Fears: Immigration and the Politics of Divide and Conquer in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, uses the debate around Hazleton’s controversial Illegal Immigration Relief Act (IIRA) as a case study that reveals the mechanics of contemporary divide and conquer politics and makes an important connection between immigration politics and the perpetuation of racial and economic inequality.

Dr. Daniel Stageman is the Director of Research Operations of John Jay’s Office for the Advancement of Research. His academic work examines political economy and profit in the detention of American immigrants, and the economic context surrounding federal-local immigration enforcement partnerships.

Dr. Daniel Stageman is the Director of Research Operations of John Jay’s Office for the Advancement of Research. His academic work examines political economy and profit in the detention of American immigrants, and the economic context surrounding federal-local immigration enforcement partnerships.

Dr. Isabel Martinez is an Assistant Professor of Latin American and Latina/o Studies and the Founding Director of U-LAMP, the Unaccompanied Latin American Minor Project, a research and service project that focuses on providing academic, social and legal support to recently arrived immigration minors in removal proceedings. She also serves as the faculty adviser to the JJay DREAMers club.

Dr. Isabel Martinez is an Assistant Professor of Latin American and Latina/o Studies and the Founding Director of U-LAMP, the Unaccompanied Latin American Minor Project, a research and service project that focuses on providing academic, social and legal support to recently arrived immigration minors in removal proceedings. She also serves as the faculty adviser to the JJay DREAMers club.

Recent Comments