Home » Posts tagged 'policy'

Tag Archives: policy

Policies Changing New York: Impact Magazine 2018-19

As a New York institution and part of the City University of New York, John Jay College is home to many who want to drive real-world reform to make New York communities stronger. Our unique research centers provide evidence-based partnerships and guidance that city officials and state legislators need to create better policy. Read on for a quick look at the impactful work they are doing in New York, or read the full story in our latest issue of Impact research magazine.

Easing Reentry

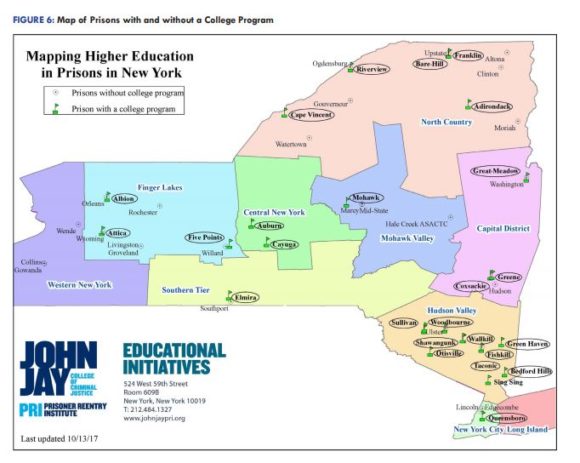

The Prisoner Reentry Institute has been a research center since 2005, when it was founded to help people live successfully in their communities after contact with the criminal justice system. The center, directed by Ann Jacobs, engages in a combination of public advocacy, direct service, and collaborative partnerships to promote a range of reentry practices, with a focus on creating pathways from justice involvement to education and career advancement.

In pursuit of that goal, PRI advocates for higher education in prisons, priming what they call the “prison-to-college pipeline.” They recently produced a report mapping higher education opportunities in New York State prisons, finding that only 3% of more than 45,000 people in New York prisons were participating in higher education programs, despite expanded funding.

PRI is also interested in post-incarceration advocacy. A work group, led by PRI’s Director of Public Policy Alison Wilkey and comprised of local stakeholders, is working to change the New York City Housing Authority’s policies excluding residents who have been arrested. The work group’s actions, including the creation of a clearer exemption application, new guidelines limiting the use of exclusions, and tenant education, have helped reduce the number of people excluded from NYCHA housing 50% from 2016 to 2018.

Interrupting Crime

A team of Research and Evaluation Center researchers is evaluating Cure Violence, a public health approach to violence reduction.The program relies on neighborhood-based workers, often with a history of justice involvement, mediating and working with younger people in the neighborhood to keep them from going down a violent path.

“Politically, it’s a difficult program to operate,” says REC Director Jeff Butts, because city officials are often wary of Cure Violence workers’ criminal histories. But REC has found that Cure Violence sites in the South Bronx and Brooklyn have seen greater violence reductions than comparison sites. According to Butts, explaining the research and the results clearly to the public is key to shifting policy. “You can’t change policy, no matter how smart you are, just by publishing articles in academic journals.”

Less Punishment, Less Crime

Violence isn’t the only type of crime that can be reduced with less punitive solutions. Director of research project From Punishment to Public Health (P2PH) Jeff Coots holds that alternatives to incarceration can not only reduce the use of prison and jail terms, but also offer rehabilitative services to people in need. “Punishment alone is not getting us the public safety outcomes we want,” he says. “How do we identify public health-style solutions that can respond where punishment does not, and isolation will not?”

Among P2PH’s signature initiatives is a pilot project to use pre-arrest diversion for minor offenses committed by the homeless. Many of those cases were previously decided at arraignment, denying arrestees the chance to connect with needed services. The pilot has reduced the number of people arrested and increased the number connected with services like transitional housing and health treatment.

In general, Coots believes policymakers are increasingly open to health interventions as an alternative to incarceration. “We don’t want the jail to be the biggest mental health provider in our community.”

Justice by the Numbers

The Data Collaborative for Justice is invested in documenting the scale of the criminal justice footprint, in New York and a network of other cities, and

considering solutions to reduce it. DCJ explores high-contact points in the system, including pretrial detention and incarceration in New York City jails. A major project for the center has been to produce an evaluation of the 2016 Criminal Justice Reform Act, passed by the New York City Council to “create more proportional penalties for certain low-level, nonviolent offenses.” With support from the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, DCJ’s evaluation shows that the CJRA seems to be achieving its aims — 90% of summonses for five high-volume offenses like noise violations and littering are now civil rather than criminal, with an associated decline in criminal warrants.

The positive impact of this legislation has the potential to push policy change in other areas by informing conversations with lawmakers. DCJ works closely with city and state agencies to gather data and make it available to policymakers so they have the resources to make evidence-based decisions. “Policy neutrality is an important part of DCJ’s mission and outlook,” says Project Director Kerry Mulligan. “That has allowed us to be a trusted broker with a diverse set of data partners.”

Among John Jay College’s research centers and projects, some researchers are building the evidence base, while others are rolling up their sleeves to help cities implement and evaluate solutions on the ground. In each case, the vital goal is making communities safer. Says REC’s Jeff Butts, “You have to put the evidence in front of [policymakers] on a regular basis in order to get the political culture to start to shift.”

For the full feature, please visit the John Jay Faculty and Staff Research page to read the whole magazine in PDF form!

Social Inclusion Leads to Violence Reduction in Ecuador – Dr. David Brotherton

Since 2007, the Ecuadorian approach to crime control has emphasized policies of social inclusion and innovations in criminal justice and police reform. One notable part of Ecuador’s holistic approach to public security was the decision to legalize a number of street gangs in 2007. The government claimed this decision contributed to the reduction of homicide rates from 15.35 per 100,000 in 2011 to close to 5 per 100,000 in 2017. Professor of Sociology David Brotherton was commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank to spend six months evaluating these claims through a qualitative research project focusing on the impact on violence reduction had by street gangs involved in processes of social inclusion. The results were published in 2018, arguing that social inclusion policies helped to transform gang members’ social capital into a vehicle for behavioral change. In December 2018, Dr. Brotherton was awarded a grant by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation to continue the work.

Since 2007, the Ecuadorian approach to crime control has emphasized policies of social inclusion and innovations in criminal justice and police reform. One notable part of Ecuador’s holistic approach to public security was the decision to legalize a number of street gangs in 2007. The government claimed this decision contributed to the reduction of homicide rates from 15.35 per 100,000 in 2011 to close to 5 per 100,000 in 2017. Professor of Sociology David Brotherton was commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank to spend six months evaluating these claims through a qualitative research project focusing on the impact on violence reduction had by street gangs involved in processes of social inclusion. The results were published in 2018, arguing that social inclusion policies helped to transform gang members’ social capital into a vehicle for behavioral change. In December 2018, Dr. Brotherton was awarded a grant by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation to continue the work.

What did you learn during the initial phase of your research?

We learned a lot. These are very large groups, with over 1,000 members spread across Ecuador, and they managed to create a new kind of culture within their organizations that was pro-social, pro-community, with a strong element of conflict resolution and mediation, cultures where they were working as partners with the government and non-state actors like universities on progressive agendas. They were partners in pro-social activities, everything from creating new youth cultures to voting, job training, and strengthening local communities, all of which you don’t associate with street gangs. And in their ranks are the most marginalized youth of their country, so they can reach kids that are so marginal that other organizations don’t reach them, even indigenous kids from the Amazon, and it is so important to bring them in and work with them. This is all across Ecuador.

When we asked the members what had changed, they said they don’t get into the same level of conflict. Where there might have been a previous period where they were at war with one another, they were able to end it with the government playing a role.

Sometimes these interventions don’t last very long, once the money runs out, but here you had a government that constantly maintained a presence and lived up to its promises, so the trust level became really high.

The end result is not necessarily unique, we’ve seen this in other places like with the Latin Kings in New York and various places in Spain, but the outcome across ten years was quite remarkable. Homicide rates are so indicative of a country’s ability to resolve tension, so when you see the inarguable statistics of homicides going down every year for ten years — it’s related to different factors, they also reformed the police department, but when you see that kind of result it’s pretty impressive.

What key aspects of the inclusion policy allowed gangs to successfully transition from criminal to purely social organizations?

The government recognizes that they won’t change overnight, because the economic situation doesn’t allow that, but you make it such that whatever [gangs] are involved in doesn’t hurt the community, and there are other pathways they can move into and you are creating real opportunities. So what does that look like? It looks like being recruited into programs at the university to give you skills, diploma programs. And these kids become a kind of role model for their mates.

In addition to that, [all of the gangs] were incorporated as non-profit organizations, which allows them to get government grants to do things like community building. You’re not just rhetorically arguing for a new culture, you’re making a new culture and making it happen. Those joining the organization come in with a different set of expectations, and it has a tremendous ripple effect. They created a strata of professional workers.

Also, the police are told not to pick them up, or intervene in their meetings. And the kids don’t fear any kind of stigma, they’re not constantly being harassed. With the communitarian police force, they worked with the heads of the police. It’s a totally unique phenomenon, and flies directly in the face of what we’re pushing in the U.S., which is zero tolerance.

Where else might this social inclusion approach be effective in curbing violence?

I mean, it could be effective in the U.S. Social inclusion is the complete opposite of the repressive policy that nearly always leads to what we call deviant amplification. You need to stop the stigmatization and have meaningful relationships with street groups, with intermediaries from the government. In the U.S., the police are so strong that this is all very difficult.

To make this work anywhere, politically you need to make a decision about where to invest resources. [In Ecuador,] they didn’t invest in the military, they didn’t invest in massive tax breaks for corporations, in fact they did the opposite. They boosted money for culture and art. If you stick with these political decisions, they will pay dividends over time.

What is the next step in completing this research?

I have a full-time field researcher, Rafael Gude, who has been working in Ecuador since April, focusing on the relationship between the Catholic University of Quito and the Latin Kings and Queens. I’m going down myself July 3-15 to do field work both with the Latin Kings and Queens and to attend a big national meeting in Cuenca, then I travel to Las Esmeraldas, on the Pacific coast of Ecuador, where we will interview members of the third major street organization in Ecuador, called Masters of the Street. We want to understand the changes in that group and the roles of social and political empowerment in the reduction in violence.

Las Esmeraldas had the highest rate of violence, with a really high homicide rate of around 70 per 100,000, which is now down to 20, and it’s on the border with Colombia so this is the biggest drug trafficking area and also very poor. This is a completely different socio-economic context, and mainly black Ecuadorians, so we want to see how the whole issue of race works itself out as they’re trying the same policy.

Also, things have changed; although the same party is in power, it’s not the same government. We thought they were going to completely reverse the policy, but a number of media organizations got into this report, and I gave this big talk in Medellín last year, and it’s become a real media story about this success. So this government has maintained the same policy, and embraced it as much or more than the last government.

Right now, we are also looking to do work in the prisons where the inmate population has increased substantially in recent years and many of the incarcerated have joined the groups.

Why is it important to continue this research?

The importance of this work is that it demonstrates a viable alternative to “zero tolerance” and other repressive policies that led to the highest homicide rates in the world — for example, in Central America’s Northern Triangle. The topic has been covered by the BBC and is out in English, Spanish and Portuguese, with multiple other Latin American nations now taking notice, including the president of Mexico.

How does your research dovetail with the HFG Foundation’s mission?

The research meshed with their general focus; they’ve always supported innovative anti-violence or violence prevention studies. For them to come on board, it’s a big deal.

You can learn more about the first stage of this research via the report on the Inter-American Development Bank’s website, or by listening to him talk about his research on the BBC program The Inquiry (starts at 13:43) or on the Peter Collins Show podcast.

Dr. David Brotherton is a Professor of Sociology at John Jay College and the CUNY Graduate center. He is the author of a number of books on gangs and immigration, most recently co-authoring Immigration Policy in the Age of Punishment: Detention, Deportation, and Border Control. He is a founding member of the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime research working group based at the Center on Social Change and Transgressive Studies at John Jay.

John Jay Scholars on the News – Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA and Dreamers)

Hundreds of thousands of immigrants to the United States who arrived as children were protected by the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which allowed them to live, study and work in the country. Shortly after entering office, Donald Trump put a (currently defunct) deadline on phasing out the program and asked Congress to create a permanent solution which has not yet emerged, making these hundreds of thousands of immigrants into a political football and creating extreme anxiety about their futures. Despite professed political will on both sides of the aisle to keep DACA program beneficiaries (often conflated with Dreamers, or supporters of a Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act) in the country, the process of creating a legislative solution to protect these individuals has gotten bogged down amid new debate over levels of legal as well as illegal immigration, discussion of building a wall on the US’s southern border, and related issues. As a case makes its way through the courts, there are currently no signs of progress being made, whether on a short- or long-term solution for Dreamers, or for comprehensive immigration reform more broadly.

The fight over Dreamers is ongoing, thanks to a court order staying the Trump Administration’s directives to terminate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and continuing Congressional inaction toward creating a path to citizenship. What do you think is the ideal fix for Dreamers?

Jamie Longazel (Associate Professor, Political Science): Some may argue that blanket citizenship for Dreamers is not possible, but I’m a firm believer in working to expand the realm of possibility.

Isabel Martinez (Assistant Professor, Department of Latin American and Latina/o Studies): The ideal legislative fix for Dreamers is a pathway to citizenship that is not punitive and takes into account the many years that they have lived in the United States. This means eliminating the conditional permanent resident provisions that have been included in several versions of the “Dream Act” that in some cases mandate thirteen total years before the ability to apply for citizenship; lowering application fees; and widening the ability to regularize status. Better legislation would raise the limit on the age of arrival (now sixteen) and remove the maximum age (currently thirty). It would also include a way for Dreamers’ parents to regularize their statuses, either via sponsorship by Dreamers or other citizen children, or on their own. It is wholly punitive to grant children of immigrants a pathway to citizenship and not their parents.

Dan Stageman (Director of Research Operations, Office for the Advancement of Research): Dreamers are a particularly sympathetic class of immigrants because they fit into the American narrative of meritocratic achievement, and because they were too young to be seen as culpable for the “crime” of their unauthorized presence in the US. In a moral sense, however, they are no more deserving of citizenship than low-wage immigrant workers who underpin significant sectors of the American economy, who pay taxes, and contribute to their communities of residence in countless ways. Perhaps more importantly, Dreamers are connected to this supposedly less deserving segment of the undocumented population through family ties and social bonds. So no legislative fix that focuses narrowly on Dreamers is intrinsically good for them – it is simply seen as more politically possible than a genuinely inclusive and comprehensive approach to legislation.

Part of the problem with making a push toward legislative change is that issues tend to fall out of the news cycle or be supplanted by newer and bigger issues. How can activists keep DACA at the forefront of legislators’ minds and continue to push for change?

Isabel: Immigration activists have been fighting for a Dream Act for sixteen years, but what is hopeful is that we are currently seeing the highest percentages of voters supporting a way for Dreamers to remain in the country legally. Activists and allies must be media and politically savvy and ensure that this support continues and grows, and is continuously broadcast to legislators. This means that DACA activists and allies must be media and politically savvy. Media and legislators must also do the right thing to build further support to get a law passed.

Jamie: I think activists deserve a lot of credit for keeping this conversation going, despite the media’s tendency to get bored and move on. My sense is that, within activist circles and immigrant communities, this issue hasn’t gone away at all, even if the national media has stopped covering it and we have temporarily lost legislators’ attention.

One helpful tactic for activists to consider as they try to build the power necessary to enact meaningful change is issue linking. DACA is about immigration, but it’s also about economic injustice, race, and unequal access to certain rights and privileges. By bringing DACA recipients and other undocumented folks into the conversation on, say, universal healthcare (and vice versa), not only does the issue stay on the agenda, but it also helps to boost cross-issue solidarity where we’d otherwise have activists working in silos.

Dan: What is striking is when you see groups like United We Dream – an undocumented youth grassroots organization – shifting their focus to providing practical support for immigrants facing deportation. It’s an indication that the faith these groups place in the political process to solve their very real and immediate human problems is at a low ebb.

Can you state the case for allowing Dreamers to stay in the United States?

Isabel: Dreamers are already Americans! They have assimilated – the only thing that separates them from other young people is a piece of paper. Removing Dreamers would be removing Americans, as well as much-needed talent and potential in which this country has already invested. Additionally, sending Dreamers back to countries and communities that they do not know and where they do not possess social ties is setting them up for failure. These countries have limited plans to receive and integrate them.

Jamie: I don’t think Dreamers are especially deserving because they are high achieving or assimilated. Claims like these can reinforce notions of “us” versus “them” that have long plagued the immigration debate. I think they are deserving because they are human beings, because no one deserves to live in fear, because no one deserves to be denied access to basic rights. I think Dreamers should be permitted to stay in the United States because it is the right thing to do.

Isabel: The other case is rooted in the United States’ obligations as an imperialist state: the majority of DACA recipients are Mexican, approximately 79%. Their arrivals to the United States coincided with the shocks or aftershocks of economic deals, including NAFTA, made between the US and Mexico that had losers as well as winners, namely many poor Mexican families who could no longer survive due to conditions of the deals. If we look at other countries of origin including the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and El Salvador, we see immigration as the effect of failed or highly lopsided bi-national policies enacted with the United States. This is considered alongside increased border militarization that made the conditions of circular migration deadly and expensive for adult migrants like these young peoples’ parents. The United States has had its hand in the conditions that pushed many families from these communities to enact strategies that let them survive together; as such, the United States has a moral obligation to right these wrongs by receiving and integrating Dreamers and other immigrants.

Dan: I would again broaden the lens to include all “unauthorized permanent residents,” a group that includes any individual who has built the kinds of social and economic ties to the US that are the essential features of establishing long-term community membership, but is unable to legalize their presence. That definition in and of itself makes the case: the ethical framework for community membership goes back at least to Rousseau’s Social Contract, and the mutual obligation it establishes between the individual and their society. Dreamers and other unauthorized permanent residents are fulfilling their end of the social contract through their economic and cultural contributions to American life; unfortunately, the federal government has not reciprocated. Congress passed the last comprehensive immigration law in 1996 – over 20 years ago. The heartbreaking stories that have recently become so common, of individuals deported after 20, 30 or 40 years of US residency, are the direct result of Congress’s historic refusal to address the instability and vulnerability these immigrants have faced throughout their time in the country.

The reality is that vulnerable people are easy to exploit – illegality is, in effect, an informal guest worker program that allows the US economy to benefit from Dreamers and other unauthorized permanent residents without providing for their welfare. This is also why local governments and private prison companies have been able to take increasingly entrepreneurial approaches to their involvement in immigrant detention and deportation. The simple case for a path to citizenship is that these forms of exploitation are morally repugnant and un-American.

What is the best thing others can do to support the Dreamers?

Jamie: If we are talking about folks who are not immigrants, or immigrants who do not have a precarious legal status, then my suggestion would be to stay active – attend rallies, share information, or join an organization. And I think folks should think hard about how our struggles are intertwined. Solidarity is how otherwise powerless groups become powerful. But it is important that Dreamers and other affected immigrants lead the way, because sometimes well-intended actions and words from unaffected people can do more harm than good.

Dan: Give generously to advocacy organizations like the New York Immigration Coalition or the Immigrant Legal Resource Center. Write and call senators and congresspeople in support of DACA legislation. Most importantly, learn about the needs and vulnerabilities of immigrant communities where you live and work, and intervene in whatever way you can.

CUNY has one of the largest populations of Dreamers of any university system in the country, and while it would be irresponsible for any institution to tell these students that we can keep them safe from deportation, we can find other ways to help alleviate the incredible stress they’ve been under since the 2016 election; for example, establishing scholarships and emergency support funds, holding regular legal clinics, providing physical and mental health services, and ensuring the confidentiality of their education data are some of the things that CUNY has taken on to support our Dreamers.

Isabel: Individuals can follow our lead at John Jay for local-level support. For college-going Dreamers, we will be opening an Immigration Student Success Center in the fall that will centralize resources – academic, financial, social and legal – that are essential to their success. This is the culmination of two and a half years of work that focused on creating systems to protect, support, and empower our John Jay Dreamers.

In addition, according to a variety of polls the majority of Americans support a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers. Voters need to turn that passive support into active support and pressure their representatives to vote on a bill ASAP, with calls, emails, visits, op-eds and town hall testimonials that share how important it is that this issue is resolved. This pressure should be placed at all levels of government and in the private sector. Private citizens and corporations can advocate for state and local government to support Dreamers by passing bills that provide in-state tuition, state financial aid, and drivers’ licenses; allow them to obtain professional licenses to practice medicine and law, or teach; and restrict cooperation with DHS and ICE.

Some states and institutions are instituting limited solutions for DACA recipients, like a bill proposed in Rhode Island to allow DACA recipients to obtain drivers licenses and work permits despite expired federal status, or certain universities helping with DACA renewal fees or offering special opportunities for non-citizenship-dependent research and educational opportunities. How helpful do you think these solutions are in mitigating the current circumstances Dreamers find themselves in?

Isabel: These are very helpful, but aren’t enough. In-state tuition and financial aid can mean the difference between DACA recipients enrolling or not in college, and, once enrolled, stopping frequently to save money or paying by semester. And of course, there are significant wage differentials between those with and without college degrees or professional development opportunities. Providing funding for internships and research enables DACA recipients to position themselves to procure better (status and –paying) jobs during school and after graduation.

Dan: While state and local-level solutions are not a replacement for comprehensive federal immigration reform including a path to citizenship, they are absolutely necessary in its absence. Most important among these solutions are the ones that, like California’s recent SB-54, limit law enforcement data sharing and cooperation with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). It’s important for states and localities to announce their intentions to protect their communities from arbitrary detention and deportation, and follow through with legally binding statutes that prevent local law enforcement agencies from contributing to the process in any way.

Jamie: What I appreciate most about measures like this is their symbolic power. These places are leading by example. They’re showing us what inclusion could look like, showing us that they are not afraid, and expanding our collective sense of what is possible.

Does the focus on DACA recipients in the news and policy debate overlook other undocumented immigrants, or ease their own paths toward citizenship? Do you believe this debate will end up helping all undocumented residents?

Dan: I think overall the focus on DACA recipients does a disservice to other undocumented immigrants. It sets up a contrast between the supposedly achievement-oriented, ‘model immigrant’ Dreamers, and their hard-working (but often low-wage) parents and neighbors who are no less deserving. This is a false dichotomy, and not one that anyone who supports immigrant rights should be playing into.

Jamie: I think the focus on DACA recipients has overlooked other undocumented immigrants, but only because of the way the issue has been framed (i.e., depicting DACA recipients as deserving in contrast to other undocumented folks). There are plenty of other ways we can frame the issue that are actually favorable to immigrants across the spectrum of legal statuses.

For instance, I think talking about children who were brought to the United States without authorization can complicate what is otherwise a rather simplistic immigration debate. People talk about “legal” and “illegal” immigration as though there is a binary that is synonymous with “good” and “bad.” But here we see that the reality is far more complicated. DACA also opens up an opportunity to talk about nuances that many non-immigrants are unaware of: mixed-status families and the unique experiences of “1.5 generation” immigrants, to name a couple of examples.

What I’m saying is that so much of our public debate has relied on stereotypes and myths! With DACA, I think we have an opportunity to confront and challenge those myths, but we have to be very careful not to reinforce them.

(Answers may be lightly edited for clarity.)

Dr. Jamie Longazel is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at John Jay College. His research examines issues of race and political economy, typically within the contexts of immigration and imprisonment. His recent book, Undocumented Fears: Immigration and the Politics of Divide and Conquer in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, uses the debate around Hazleton’s controversial Illegal Immigration Relief Act (IIRA) as a case study that reveals the mechanics of contemporary divide and conquer politics and makes an important connection between immigration politics and the perpetuation of racial and economic inequality.

Dr. Jamie Longazel is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at John Jay College. His research examines issues of race and political economy, typically within the contexts of immigration and imprisonment. His recent book, Undocumented Fears: Immigration and the Politics of Divide and Conquer in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, uses the debate around Hazleton’s controversial Illegal Immigration Relief Act (IIRA) as a case study that reveals the mechanics of contemporary divide and conquer politics and makes an important connection between immigration politics and the perpetuation of racial and economic inequality.

Dr. Daniel Stageman is the Director of Research Operations of John Jay’s Office for the Advancement of Research. His academic work examines political economy and profit in the detention of American immigrants, and the economic context surrounding federal-local immigration enforcement partnerships.

Dr. Daniel Stageman is the Director of Research Operations of John Jay’s Office for the Advancement of Research. His academic work examines political economy and profit in the detention of American immigrants, and the economic context surrounding federal-local immigration enforcement partnerships.

Dr. Isabel Martinez is an Assistant Professor of Latin American and Latina/o Studies and the Founding Director of U-LAMP, the Unaccompanied Latin American Minor Project, a research and service project that focuses on providing academic, social and legal support to recently arrived immigration minors in removal proceedings. She also serves as the faculty adviser to the JJay DREAMers club.

Dr. Isabel Martinez is an Assistant Professor of Latin American and Latina/o Studies and the Founding Director of U-LAMP, the Unaccompanied Latin American Minor Project, a research and service project that focuses on providing academic, social and legal support to recently arrived immigration minors in removal proceedings. She also serves as the faculty adviser to the JJay DREAMers club.

Recent Comments