Home » 2020

Yearly Archives: 2020

Richard Ocejo – Understanding Small City Gentrifiers

The outbreak of COVID-19 has accelerated a number of existing trends in the United States; along with giving a big boost to remote work and the digital economy, and reinforcing existing socioeconomic inequality, 2020 has also seen the trend of movement from big cities to smaller ones pick up. Whether because larger cities are too expensive or because COVID-19 made them feel not just dense but claustrophobic, residents have reconsidered their environments. While big cities like New York and San Francisco have seen their populations decline over the last five years, some smaller cities – with populations in the tens of thousands rather than the millions – have been seeing an upswing.

Dr. Richard Ocejo, a John Jay professor, sociologist and author, is interested in what it looks like when newcomers arrive in small cities. He’s using Newburgh, New York, a city of about 30,000 in the middle of the Hudson Valley, as a case study, spending time with new and old residents to learn what gentrification looks like in a smaller city. “Newburgh was totally abandoned,” says Ocejo. “Capital had left it, investment had left it, it was just a place to warehouse the poor and struggling. Until New York City became too expensive, then all of a sudden, small, affordable, historic places like Newburgh become valuable again, to a group of people who are looking for these urban lifestyles.”

Gentrifying a Small City

Ocejo sees the characteristics of small-city gentrifiers as distinct from those who have traditionally moved into gentrifying neighborhoods in New York City, like on the Lower East Side or in Brooklyn. People moving to small cities from places like New York are often middle class, mid-career professionals, who are looking to buy property more affordably while still maintaining the lifestyles and habits they developed in the big city. Over the course of several years of field work and interviews, Ocejo has pinpointed some common threads in the narratives Newburgh’s newest residents use to understand their actions.

“They recognize that the reason they left [New York City] was because of being priced out. But when they get to Newburgh, the understanding of what it’s like to not be able to afford a place any more, of having to leave one’s home as a consequence of these larger forces beyond your control, doesn’t resonate in how they understand gentrification as they are perpetuating it in this small city,” says Ocejo. “They don’t see what they’re doing there as gentrifying that will cause this sort of harm that could make somebody leave their home as they had to do. Instead they say, we’ll just do it better.”

Generally, Newburgh’s gentrifiers are opposed to harmful development by “slumlords” or “bad actors;” in contrast, they perceive themselves as providing employment and adding to the tax base. But Ocejo hasn’t seen concrete evidence to back up their narratives. “I don’t know many examples of what we can call a successful gentrification, at least not at any kind of scale,” says Ocejo. “I can’t think of any examples of an equitable integration where there aren’t tensions and conflicts that take place.”

Reckoning with Racism

Ocejo says that some of the challenges he sees playing out in Newburgh are tied into structural racism and the failure of newcomers to acknowledge that they are recreating harmful racial and economic dynamics in Newburgh that caused displacement in New York City. While he observed Newburgh’s newcomers participating in Black Lives Matter protests and marches, he says that the leap to understanding the racist structures that are tied up in gentrification is rarely made. “We don’t talk about gentrification as a racial process,” Ocejo says, “but it is. It’s this extraction of value from racialized spaces, non-white spaces that are taken advantage of through these processes. And that’s not discussed at all.” He says gentrifiers’ inability or unwillingness to confront these issues is exacerbating a key inequality at the heart of the process.

Gentrifying “Better?”

Ocejo does clarify that, although on the whole gentrified spaces tend to end up segregated socially and culturally, there are positives associated with the process. Smaller cities are crying out for even a fraction of the investment New York City has received and, done correctly, municipal revitalization can make a real difference to disadvantaged communities. And in interviews with existing Newburgh residents, he has generally heard people react positively to commercial development in their neighborhoods. However, they aren’t necessarily sure the changes will add up to much real change in their own lives.

“Gentrification is a consequence of much larger forces that are beyond anybody’s control,” says Ocejo. Newburgh’s population of gentrifiers are responding to market forces that are making New York City a difficult place to live long-term without making significant sacrifices or acquiring millions of dollars. But at the end of the day, some groups have the means to make choices about where they will live and whether they will stay or go, while others are unable to make the same choices. It will take structural, policy-based change to make gentrifying urban neighborhoods, and migration in general, more equitable.

Dr. Ocejo has published three papers related to his work in Newburgh and has two additional papers under review. He is also working on the manuscript of a book that will bring together all of his work on this project; he expects it to come out in 2022 or 2023.

Dr. Richard Ocejo is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and the Director of the MA Program in International Migration Studies at the Graduate Center of CUNY. His research, which has been published in a variety of journals including Journal of Urban Affairs, Sociological Perspectives, and more, focuses on cities, culture and work. He uses primarily qualitative methods in his scholarship. Dr. Ocejo is the author of two books: Masters of Craft: Old Jobs in the New Urban Economy (2017) – on the transformation of manual labor occupations like butchering and bartending into elite occupations – and Upscaling Downtown: From Bowery Saloons to Cocktail Bars in New York City (2014) – about the influence of commercial operations on gentrification and community institutions in downtown Manhattan.

Dr. Richard Ocejo is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay College, and the Director of the MA Program in International Migration Studies at the Graduate Center of CUNY. His research, which has been published in a variety of journals including Journal of Urban Affairs, Sociological Perspectives, and more, focuses on cities, culture and work. He uses primarily qualitative methods in his scholarship. Dr. Ocejo is the author of two books: Masters of Craft: Old Jobs in the New Urban Economy (2017) – on the transformation of manual labor occupations like butchering and bartending into elite occupations – and Upscaling Downtown: From Bowery Saloons to Cocktail Bars in New York City (2014) – about the influence of commercial operations on gentrification and community institutions in downtown Manhattan.

Muath Obaidat Proposes a Better, Safer Way to “Log-In”

Have you ever been faced with a photo grid and asked to click on every traffic light to prove you weren’t a robot before your could access your email or bank? A recent proposal by Dr. Muath Obaidat, an Assistant Professor in John Jay College’s Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, could prevent you from having to go through that ever again.

Have you ever been faced with a photo grid and asked to click on every traffic light to prove you weren’t a robot before your could access your email or bank? A recent proposal by Dr. Muath Obaidat, an Assistant Professor in John Jay College’s Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, could prevent you from having to go through that ever again.

Along with co-authors including his student Joseph Brown (a 2020 graduate who earlier this year was awarded John Jay’s Ruth S. Lefkowitz Mathematics Prize), Dr. Obaidat makes the case for a new way of authenticating user information that would make logging into websites more secure without overcomplicating the system. He calls it “a step forward” both technically and logistically, as the proposed authentication system is both technically more secure and easier to deploy commercially than previous proposals. So while Obaidat’s research may seem complicated, the solution he proposes in “A Hybrid Dynamic Encryption Scheme for Multi-Factor Verification: A Novel Paradigm for Remote Authentication” (Sensors, July 2020) is not just theoretical.

(To read the full text of the article for free, visit https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/20/15/4212/htm)

Read on for a Q&A with Dr. Muath Obaidat:

Can you describe the most common risks of the typical username/password authentication model most of us are using today?

The most common risk in current authentication models is the lack of presentation of actual proof of identity, especially during communications. Since the majority of websites use static usernames and passwords that do not change between sessions, if an attacker can get ahold of a login — whether by guessing or through more technical means — there is no further mechanism or nuance in design to actually stop them from using stolen data to imitate a user. While 2FA (Two Factor Authentication) has risen in popularity as a mitigation for this problem, both published papers from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) as well as high profile public hacks have shown this to be insufficient by itself, because of attacks which focus on manipulating or stealing data rather than simply brute-forcing (working through all possible combinations through trial-and-error to crack a passcode).

Can you explain how your proposed method works to authenticate a session?

The simplest way to explain how this form of authentication works is to imagine you had a key split into two halves; the client has a half, and the server has a half. But instead of just sending the half of the key you have, you’re sending the blueprint for said key half, which can only be reconstructed given the other half. This blueprint changes slightly each time you log in, but is still derivative of the other “whole” key.

Only two people have the respective halves: the client and the server. These halves are derivative of data which is itself derived from an original input. Thus, as long as you can produce something from the front-end that creates one input, even though this input is never sent, it can be integrated with this system. Think of that as the “mold” from which the key is derived, and then the blueprint is shifted on both ends according to the original mold.

How does your proposed scheme differ from others that have been in use or proposed previously?

What sets it apart is both the flexibility of the design as well as the range of problems it attempts to fix at one time. Many other schemes we studied were focused on fixing one problem: typically [they focused on] brute-forcing, which manifested in the form of padding “front-end” or “back-end” parts of a scheme without giving much thought to the actual transmission of data itself. Our scheme, on the other hand, is focused on protecting that transmitted data, while also being sure not to introduce additional weaknesses on either end of the communication.

Another big issue we often ran into with other schemes is design flexibility; many were either unrealistic to implement en masse, or were so specific that they pigeonholed themselves into a scenario where they could not be combined with other communication systems or improvements to other architectural traits. Our scheme is flexible in terms of architectural integration — for example, it uses the same simple Client-Server framework without introducing third parties or other nodes — and the overall design is both simplistic in terms of implementation and highly adaptable.

What is it that has prevented many newly-proposed authentication schemes from being implemented more broadly?

While it depends on the scheme in question, there are typically three factors that are preventative to implementation: user accessibility, deployment complications, and degree of benefit. The first isn’t really technical, but relates more to consumer factors. Many schemes simply are not widely implementable on a consumer level; not only because of aspects such as speed, but also because of logistics. Having a user go through a complicated process each time they want to log into a website isn’t very practical, especially if you’re selling a product where convenience is a factor, hence why some schemes don’t catch on despite being technically sound.

Deployment complications, on the other hand, would be related to things such as how to replace current infrastructure with new infrastructure; many schemes significantly stagger architectures or are high specific and complex to actually deploy. These complications act as a deterrent to those who may want to implement them. Lastly, degree of benefit is a big factor too. Given how ubiquitous current paradigms are, simply improving one aspect in exchange for the implementation of a widely different system is a very big ask. Implementation takes time, as does adoption on a wide scale, so unless the benefit is [significant enough to merit departing from] current paradigms, it’s unlikely many would want to explore “unproven” adoptions.

How would a new authentication method go from being theoretical to being widely adopted? In other words, by what process is this type of new technology adopted, and who is responsible for its uptake?

That’s a good question, and I do not think there is a singular answer unfortunately. Especially because of the decentralization of the internet, it’s hard to give a specific answer on what this would look like in practice. As the internet has been more consolidated under specific companies, I suppose one answer to this would be that bigger companies would have to take an interest in implementation and take action themselves to create a ripple effect. This is distinct from the past, when collective normalization of technology was bottom-up because of more decentralized standards.

Dr. Muath Obaidat is an Assistant Professor of Computer Science and Information Security at John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City University of New York and a member of the Center for Cybercrime Studies, Graduate Faculty in the Master of Science Digital Forensics and Cyber Security program and Doctoral faculty of the Computer Science Department at the Graduate School and University Center of CUNY.

He has numerous scientific article publications in journals and respected conference proceedings. His research interests lie in the area of digital forensics, ubiquitous Internet of Things (IoT) security and privacy. His recent research crosscuts the areas wireless network protocols, cloud computing and security.

Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues 2020-23

The Office for Academic Affairs through its Office for the Advancement of Research, in collaboration with Undergraduate Studies and a faculty leadership committee representing Africana Studies (Jessica Gordon-Nembhard), Latinx Studies (José Luis Morín), and SEEK (Monika Son), sponsored a year-long community dialogue on racial justice research and scholarship across the disciplines. John Jay College faculty, students, and the broader community were invited to join four panel discussions and four hands-on workshops that invited a more in-depth discussion about changing the ways we teach and learn – specifically, by facilitating meaningful engagement with scholarship by and about people of color, and promoting the incorporation of research on structural inequities into curriculum college-wide. Over the course of the 2020-2021 academic year, events covered multi-dimensional topics including:

- racial disparities in health and mental health and trauma-informed pedagogy;

- the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative;

- economic inequality; and

- racism and discrimination in the criminal legal system.

Each panel was facilitated by a John Jay faculty member who also led a follow-up workshop intended to engage participants more deeply in the subject matter and promote best practices for cultivating racial justice in our classrooms and around the college. Each panel was recorded, and the recordings can be found below, as well as resource guides for further self-guided learning and curricular reform.

Series events, recordings and resources

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Panelists: Dr. Michelle Chatman (UDC) & Dr. Lenwood Hayman (Morgan State University)

Facilitator: Dr. Monika Son (JJC)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/NYTxARHOALw

Resources:

- Ayers, W., Ladson-Billings, G., & Michie, G. (2008). City kids, city schools: More reports from the front row. The New Press. Introduction, pgs 3-7.

- Chatman, MC. (2019). Advancing Black Youth Justice and Healing through Contemplative Practices and African Spiritual Wisdom. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 6(1):27-46.

- Monzó, L. D., & SooHoo, S. (2014). Translating the academy: Learning the racialized languages of academia. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(3), 147–165. DOI: 10.1037/a0037400

- Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Arch of Self, LLC, https://www.yolandasealeyruiz.com/archaeology-of-self

For additional suggested readings, prompts for discussion, and curricular resources, download our full event guide: RJD Event 1.1 Homework and Readings.

Event #2: Race and Historical Narrative — Correcting the Erasure of People of Color

The second panel in the OAR/UGS Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues series, on November 11 at 3 pm, will shine a light on the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative commonly taught in the United States. This erasure is harmful to students of color in particular, as they do not see themselves represented in the stories told about this country, and actively harms people of all races by failing to present an accurate picture of the country’s founding and history.

Panelists: Dr. Paul Ortiz (UFL) & Dr. Suzanne Oboler (John Jay College)

Facilitator: Dr. Edward Paulino (John Jay College)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/WRIDHIA_a94

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the RJD Event 2.1 – Readings.

Event #3: Economic Inequality and Wealth Disparities

Panel Discussion – March 24, 2021, 4:30 – 5:45 pm

Panelists: Dr. Naomi Zewde (CUNY SPH) & Dr. Stephan Lefebvre (Bucknell University)

Facilitator: Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard (JJC)

Event Recording: https://youtu.be/_lp93i3EHqE

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Economic Inequalities – Resources.

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Panel Discussion – April 21, 2021, 3 – 4:15 pm

Panelists: Dr. Jasmine Syedullah (Vassar College) & Professor César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández (University of Denver, Sturm College of Law)

Facilitator: Professor José Luis Morín (JJC)

Recording: https://youtu.be/OZ8N-c7Gob0

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Resources – Racism in the Criminal Legal System

The series continued in academic year 2021-2022, expanding the scope of the discussions with panels on racial equity in disaster recovery.

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

The fifth panel took place on November 1, 2021, and addressed the interdependent roles of government agencies, community-based and non-governmental organizations in promoting or hindering equitable outcomes in post-disaster situations. Panelists included Kim Burgo (Catholic Charities), Craig Fugate (One Concern), Dr. Jason Rivera (Buffalo State College), Dr. Warren Eller (John Jay College), and Dr. Dara Byrne (John Jay College). Find the recording at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQkjxw6RcKg.

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

The sixth panel in the series, which took place on March 16, 2022, continued the theme of racial equity in disaster recovery. Panelists explored the overlapping roles of the institutions of public health and public safety in promoting equitable outcomes in post-disaster recovery, addressing the intersectional challenges faced by people of color and other marginalized communities. The conversation took special note of the particular context of post-COVID recovery. The participants were Dr. Ayman El-Mohandes (CUNY Graduate School of Public Health), Dr. Jodie Roure (John Jay College), and George Contreras (New York Medical College, John Jay College). The moderators were Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard and Dr. Charles Jennings (John Jay College). A full recording of the event is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4u9wUyjr5Sg&list=PL-B85PTQbdJj5UJhqiddjs1_9p90pZXTZ&index=6.

Resources:

- , 2020: COVID-19: A Barometer for Social Justice in New York City, American Journal of Public Health

- El-Mohandes, A., White, T.M., Wyka, K. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adults in four major US metropolitan areas and nationwide. Sci Rep

- Roure, Jodie G. The Reemergence of Barriers During Crises and Natural Disasters: Gender-Based Violence Spikes Among Women and LGBTQ+ Persons During Confinement. Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, pp 23-50, 2020.

- Jodie G. Roure, 2020 presentation: Children of Puerto Rico & COVID-19: At the Crossroads of Poverty & Disaster.

- Jodie G. Roure, Immigrant Women, Domestic Violence, and Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico: Compounding the Violence for the Most Vulnerable. The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 2019.

- Contreras GW, Burcescu B, Dang T, et al. Drawing parallels among past public health crises and COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.202.

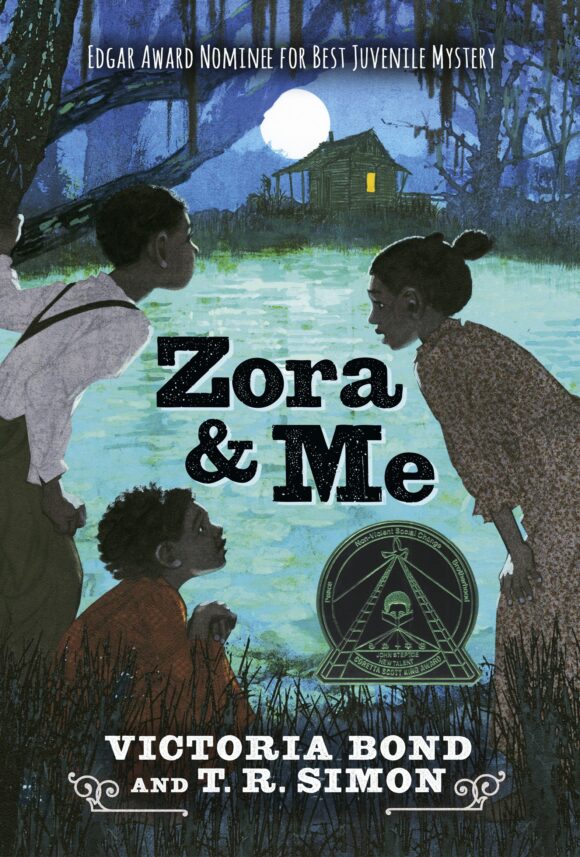

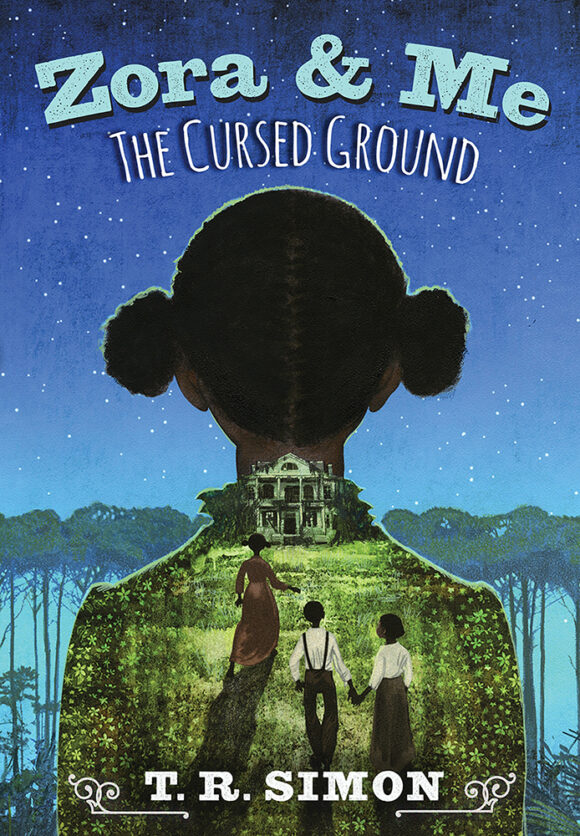

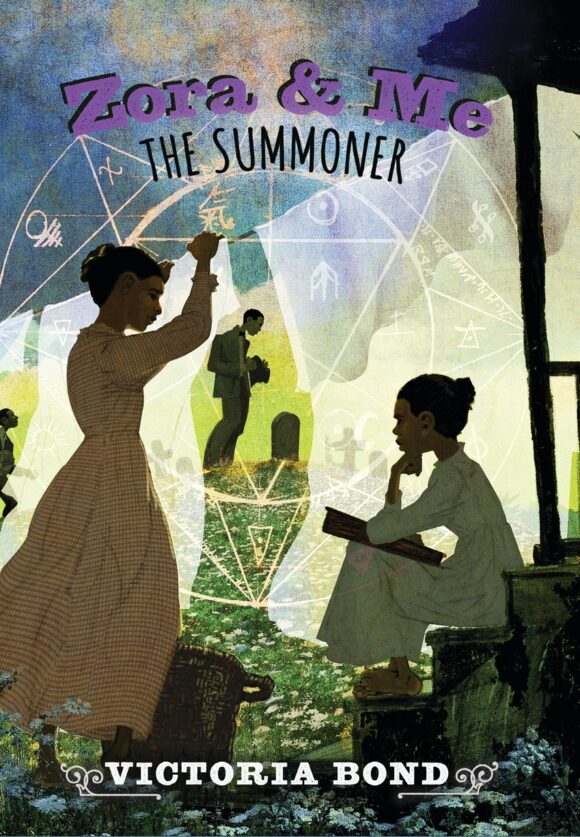

Victoria Bond’s ‘Zora and Me’ Trilogy Closes With ‘The Summoner’

Victoria Bond is a lecturer in John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s English Department, and the co-author with T. R. Simon of a series of young adult novels inspired by the childhood of American literary icon Zora Neale Hurston. The Zora and Me trilogy fictionalizes a young Zora as what The New York Times calls a “girl detective,” living in Hurston’s real-life hometown of Eatonville, Florida. Through the use of tropes from mystery and horror, the books explore community, and the fragility of justice for Black people.

In the first novel, Zora and Me, stories about a shape-shifter lead Zora and her best friend Carrie (the narrator) to solve a murder mystery. The second novel of the series, The Cursed Ground, sees Carrie and Zora learning more about the dark, unforgiveable history of slavery from a ghost. And in Bond’s latest and final novel, Zora and Me: The Summoner, Eatonville experiences upheaval that causes Zora’s family to seek their fortunes elsewhere. The use of zombies in this book, Bond says, is a way to explore the exploitation and trauma of African American lives.

Each installment of the trilogy may incorporate dark, scary elements, but, according to Kirkus Reviews, the brilliance of the novels is that they are able to render African American children’s lives during the Jim Crow era as “a time of wonder and imagination, while also attending to their harsh realities.”

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Alabama in 1891 and published several novels and many short stories, plays and essays, although she is best known for her classic Harlem Renaissance novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Zora and Me was the first novel not written by Hurston herself that has been endorsed by the Zora Neale Hurston Trust, founded in 2002. To bring the real Zora’s experiences in her hometown of Eatonville, Florida, to life, Bond and Simon researched Hurston’s life extensively by reading her biographies and her 1942 autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road. They sought to create a story right for young adult readers that was true to the historical period in which it takes place, and which features a smart, spirited Black girl with a vivid imagination, ready to inspire other girls.

Zora and Me: The Summoner is forthcoming from Candlewick Press on October 13, 2020, and available for preorder now. To learn more about Zora Neale Hurston from author Vicky Bond, watch her in this short video on YouTube. Or to learn more about the experience of writing a novel during these uniquely difficult times, read this post from the author.

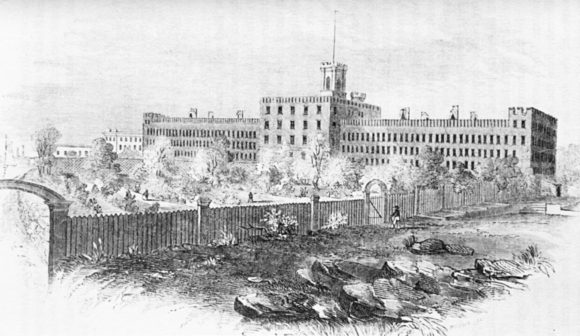

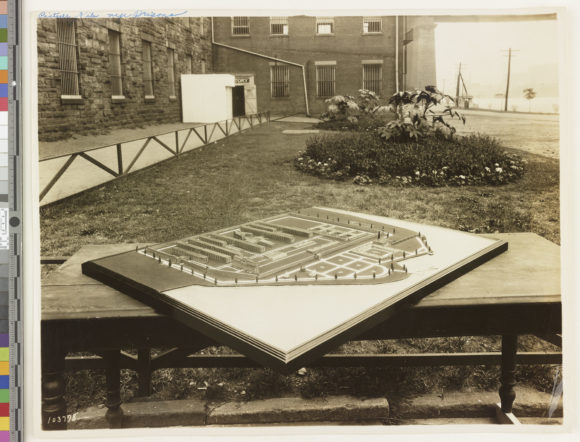

A Critical History of Incarceration in New York City

Dr. Jayne Mooney is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay and a member of the doctoral faculty of Women’s Studies and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is also a director and founding member of the Critical Social History Project (CSHP), a research initiative and part of John Jay’s Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project that draws on archival material to shed light on the history of incarceration in New York City.

The project began in 2015 with a conversation spurred by reporting on abuse, poor conditions, and a rash of tragedies at Rikers Island; how best, Mooney and colleagues wondered, to preserve the memories of those who had been affected by the infamous jail, including not only the incarcerated but also their friends and families, guards and educators? And so they began the “Other City” project, which forms the largest component of the CSHP. Informed by their research into the history of New York’s penitentiary system, Mooney’s working group is pointing out the problems inherent in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration’s proposal to close Rikers and open four new city jails.

“On the most basic level, what we’re showing is that the current proposals are reinventing the wheel. It’s the same thing that’s always happened. Closing an institution and setting it up again, you’re going to have the same problems, because you’re not getting to those deep-rooted, structural issues,” says Mooney.

Reinventing the Wheel

In a forthcoming article, “Rikers Island: The Failure of a ‘Model’ Penitentiary” due to be published in The Prison Journal in 2020, Mooney and her co-author, CUNY graduate student Jarrod Shanahan, go through the instructive failures of incarceration reform in New York City back to the 1735 construction of the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction. They argue that a lack of historical documentation has allowed policymakers to strategically “forget” the failures of past “model” or “state of the art” institutions, continually replacing old jails with new without a look at the larger issues that have led to waves of highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful penal reform.

Set against the backdrop of historical, social and political context, Rikers’ closure and the proposals to replace it look familiar. “All of these places opened in the spirit of optimism—everything was going to change. And then everything goes wrong, these institutions are denounced as embarrassments, and the decision is made to close them down and rebuild. Of course, that’s what’s been happening in the present moment,” Mooney says. She and her colleagues encourage the Mayor’s Office to look beyond the walls of the prison for new solutions to social problems faced by New York and, indeed, the United States.

(Read her December 2019 letter to The Guardian on the subject, “Rikers has failed like others before it, but the solution is not new jails.”)

Preserving Voices, Preserving Justice

Mooney’s challenge to the new proposals is grounded not only in her work in political social history, but also in her background as a critical criminologist. “There’s a very strong abolitionist line all the way through critical criminology,” she notes, which informs the way the Critical Social History Project has approached critiques of the plan to build new jails.

The CSHP isn’t only focused on documenting mass incarceration in NYC. As the Vice Chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Critical Criminology and Social Justice Division, as well as the archivist, Mooney has been accumulating archival information related to the division and the field’s history of activism. The CSHP’s Preserving Justice component, jointly directed by Mooney and Visiting Scholar Albert de la Tierra, has created an exhibition in the Sociology Department displaying some of the core critical criminology texts. It’s open to any students, faculty or staff who are interested in the history of the field and the work of its important thinkers.

Expanding Research Horizons

Mooney is proud to talk about her team of dedicated researchers, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students. With the help of their diverse experiences and interests, the Critical Social History Project is expanding its remit, from the history of Rikers Island to topics including the history of women’s incarceration, other New York carceral institutions including the Tombs and Sing-Sing, mental illness and incarceration, and more. Together, they are showing the persistence of the problems related to the history of mass incarceration, no matter where in history you begin your research—up to and including the present day.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

You can learn more by visiting the Critical and Social History Project’s website.

Using Crime Science to Fight for Wildlife

There is no question that the fashion industry causes great harm to the environment. The industry’s faddish nature, combined with the overproduction of low-cost, low-quality pieces, is designed to encourage overconsumption. Production of fast fashion garments eats up precious resources, like clean water and old-growth forests, and discarded clothing can sit in landfills for hundreds of years, thanks to synthetic materials used in construction.

According to scholars Monique Sosnowski—a Ph.D. candidate in criminal justice at the CUNY Graduate Center—and John Jay Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice Dr. Gohar Petrossian, pollution is not the fashion industry’s only crime. In a new article, they investigated what species were being utilized for the fashion industry, which is worth over $100 billion globally, in order to better understand the damage the industry causes to wildlife and wild places.

Sosnowski and Petrossian looked at items imported by the luxury fashion industry and seized at U.S. borders by regulatory agencies between 2003 and 2013. Their study found that, during that decade, more than 5,600 items incorporating elements illegally derived from protected animal species were seized. The most common wildlife product was reptile skin—from monitor lizards, pythons, and alligators, for the most part—and 58% of confiscated items came from wild-caught species. The authors also found that around 75% of seizures were of products coming from just six countries: Italy, France, Switzerland, Singapore, China and Hong Kong. The heavy involvement of the European countries was unexpected, according to Dr. Petrossian, because they are key players in fashion design and production but “don’t generally come up in broader discussions on wildlife trafficking.”

THE SCIENCE OF WILDLIFE CRIME

The paper applied “crime science, a body of criminological theories that focus on the crime event rather than ‘criminal dispositions,’ to understand and explain crime. The overarching assumption is that crime is an opportunity, and it is highly concentrated in time, as well as across place, among offenders, and victims,” says Dr. Petrossian. Their scientific approach enabled the authors to analyze patterns and concentrations in wildlife crime, which Sosnowski notes is among the four most profitable illegal trades.

“We are currently living in an era that has been coined the ‘sixth mass extinction,’” she says. “It is crucial that we understand the impact that humans are having on wildlife, from habitat loss to the removal of species from global environments. Fashion is one of the major industries consuming wildlife products.”

A background in wildlife conservation, including unique experiences like responding to poaching incidents in Botswana and rehabilitating trafficked cheetahs in Namibia, led Monique Sosnowski to a Ph.D. in criminology; she wanted to move beyond a more traditional conservation-informed approach to address what she’d seen in the field. Working with Dr. Petrossian on a series of studies applying crime science to wildlife crimes has given her a broader view of the effects of wildlife-related crime on global ecosystems.

CREATING SOLUTIONS, SAVING WILDLIFE

Why is it important to understand what species are most commonly used in luxury fashion products, and where they are coming from? A study like this one provides information about trends that policymakers can use to strengthen or focus enforcement and inform better understanding of the issues. Sosnowski calls this “the key to devising more effective prevention policies.”

Currently, global regulation of the trade in wildlife products, including leather, fur, and reptile skin that come from species both protected and not, is the province of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES); this treaty aims to ensure that international trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. But the treaty is limited in scope.

“Given the prevalence of exotic leather and fur in fashion, we believe CITES and other regulatory bodies should enact policies on its use and sustainability in order to protect wild populations, the welfare of farmed and bred populations, and the sustainability of the fashion industry,” Sosnowski says.

Consumers also have a role to play. “We are all led to believe that products found on the shelves are legal, but as this study has demonstrated, that isn’t always the case. Consumers of these products are the ones who have the power to change the behaviors of a $100 billion industry. We need to ask questions about where our products were sourced, and respond accordingly.”

###

Summarized from EcoHealth, Luxury Fashion Wildlife Contraband in the USA, by Monique C. Sosnowski (John Jay College, City University of New York) and Gohar A. Petrossian (John Jay College, City University of New York). Copyright 2020 EcoHealth Alliance.

Eric Piza is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His research focuses on the spatial analysis of crime patterns, problem-oriented policing, crime control technology, and the integration of academic research and police practice. His recent research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals including Criminology, Criminology & Public Policy, Crime & Delinquency, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Justice Quarterly and more. In support of his research, Dr. Piza has secured over $2.2 million in outside research grants, including funding from the National Institute of Justice. In 2017, he was the recipient of the American Society of Criminology, Division of Policing’s Early Career Award in recognition of outstanding scholarly contributions to the field of policing.

Eric Piza is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His research focuses on the spatial analysis of crime patterns, problem-oriented policing, crime control technology, and the integration of academic research and police practice. His recent research has appeared in peer-reviewed journals including Criminology, Criminology & Public Policy, Crime & Delinquency, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Justice Quarterly and more. In support of his research, Dr. Piza has secured over $2.2 million in outside research grants, including funding from the National Institute of Justice. In 2017, he was the recipient of the American Society of Criminology, Division of Policing’s Early Career Award in recognition of outstanding scholarly contributions to the field of policing.

Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

Recent Comments