Home » Posts tagged 'John Jay College of Criminal Justice' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Victoria Bond’s ‘Zora and Me’ Trilogy Closes With ‘The Summoner’

Victoria Bond is a lecturer in John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s English Department, and the co-author with T. R. Simon of a series of young adult novels inspired by the childhood of American literary icon Zora Neale Hurston. The Zora and Me trilogy fictionalizes a young Zora as what The New York Times calls a “girl detective,” living in Hurston’s real-life hometown of Eatonville, Florida. Through the use of tropes from mystery and horror, the books explore community, and the fragility of justice for Black people.

In the first novel, Zora and Me, stories about a shape-shifter lead Zora and her best friend Carrie (the narrator) to solve a murder mystery. The second novel of the series, The Cursed Ground, sees Carrie and Zora learning more about the dark, unforgiveable history of slavery from a ghost. And in Bond’s latest and final novel, Zora and Me: The Summoner, Eatonville experiences upheaval that causes Zora’s family to seek their fortunes elsewhere. The use of zombies in this book, Bond says, is a way to explore the exploitation and trauma of African American lives.

Each installment of the trilogy may incorporate dark, scary elements, but, according to Kirkus Reviews, the brilliance of the novels is that they are able to render African American children’s lives during the Jim Crow era as “a time of wonder and imagination, while also attending to their harsh realities.”

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Alabama in 1891 and published several novels and many short stories, plays and essays, although she is best known for her classic Harlem Renaissance novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Zora and Me was the first novel not written by Hurston herself that has been endorsed by the Zora Neale Hurston Trust, founded in 2002. To bring the real Zora’s experiences in her hometown of Eatonville, Florida, to life, Bond and Simon researched Hurston’s life extensively by reading her biographies and her 1942 autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road. They sought to create a story right for young adult readers that was true to the historical period in which it takes place, and which features a smart, spirited Black girl with a vivid imagination, ready to inspire other girls.

Zora and Me: The Summoner is forthcoming from Candlewick Press on October 13, 2020, and available for preorder now. To learn more about Zora Neale Hurston from author Vicky Bond, watch her in this short video on YouTube. Or to learn more about the experience of writing a novel during these uniquely difficult times, read this post from the author.

A Critical History of Incarceration in New York City

Dr. Jayne Mooney is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay and a member of the doctoral faculty of Women’s Studies and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is also a director and founding member of the Critical Social History Project (CSHP), a research initiative and part of John Jay’s Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project that draws on archival material to shed light on the history of incarceration in New York City.

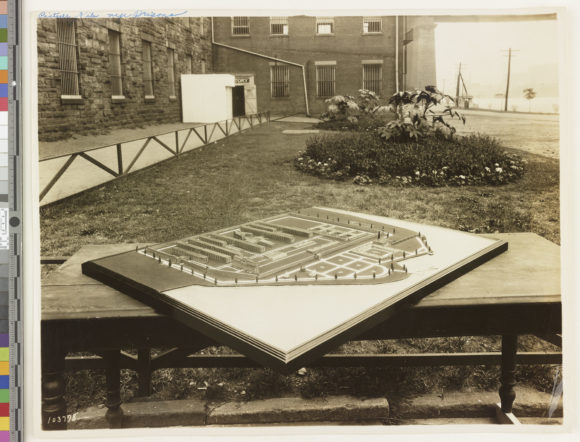

The project began in 2015 with a conversation spurred by reporting on abuse, poor conditions, and a rash of tragedies at Rikers Island; how best, Mooney and colleagues wondered, to preserve the memories of those who had been affected by the infamous jail, including not only the incarcerated but also their friends and families, guards and educators? And so they began the “Other City” project, which forms the largest component of the CSHP. Informed by their research into the history of New York’s penitentiary system, Mooney’s working group is pointing out the problems inherent in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration’s proposal to close Rikers and open four new city jails.

“On the most basic level, what we’re showing is that the current proposals are reinventing the wheel. It’s the same thing that’s always happened. Closing an institution and setting it up again, you’re going to have the same problems, because you’re not getting to those deep-rooted, structural issues,” says Mooney.

Reinventing the Wheel

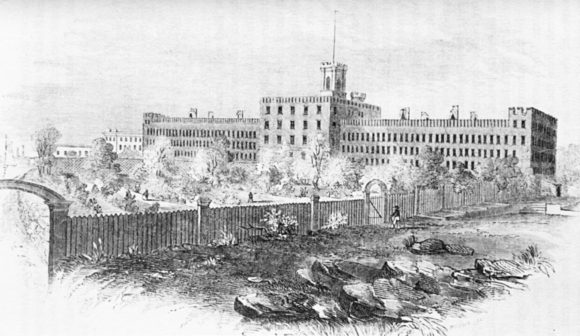

In a forthcoming article, “Rikers Island: The Failure of a ‘Model’ Penitentiary” due to be published in The Prison Journal in 2020, Mooney and her co-author, CUNY graduate student Jarrod Shanahan, go through the instructive failures of incarceration reform in New York City back to the 1735 construction of the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction. They argue that a lack of historical documentation has allowed policymakers to strategically “forget” the failures of past “model” or “state of the art” institutions, continually replacing old jails with new without a look at the larger issues that have led to waves of highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful penal reform.

Set against the backdrop of historical, social and political context, Rikers’ closure and the proposals to replace it look familiar. “All of these places opened in the spirit of optimism—everything was going to change. And then everything goes wrong, these institutions are denounced as embarrassments, and the decision is made to close them down and rebuild. Of course, that’s what’s been happening in the present moment,” Mooney says. She and her colleagues encourage the Mayor’s Office to look beyond the walls of the prison for new solutions to social problems faced by New York and, indeed, the United States.

(Read her December 2019 letter to The Guardian on the subject, “Rikers has failed like others before it, but the solution is not new jails.”)

Preserving Voices, Preserving Justice

Mooney’s challenge to the new proposals is grounded not only in her work in political social history, but also in her background as a critical criminologist. “There’s a very strong abolitionist line all the way through critical criminology,” she notes, which informs the way the Critical Social History Project has approached critiques of the plan to build new jails.

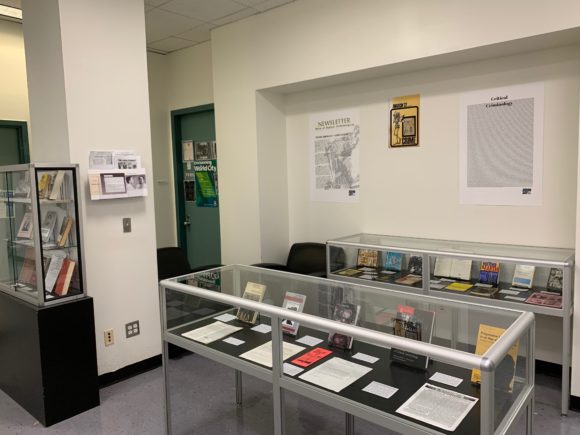

The CSHP isn’t only focused on documenting mass incarceration in NYC. As the Vice Chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Critical Criminology and Social Justice Division, as well as the archivist, Mooney has been accumulating archival information related to the division and the field’s history of activism. The CSHP’s Preserving Justice component, jointly directed by Mooney and Visiting Scholar Albert de la Tierra, has created an exhibition in the Sociology Department displaying some of the core critical criminology texts. It’s open to any students, faculty or staff who are interested in the history of the field and the work of its important thinkers.

Expanding Research Horizons

Mooney is proud to talk about her team of dedicated researchers, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students. With the help of their diverse experiences and interests, the Critical Social History Project is expanding its remit, from the history of Rikers Island to topics including the history of women’s incarceration, other New York carceral institutions including the Tombs and Sing-Sing, mental illness and incarceration, and more. Together, they are showing the persistence of the problems related to the history of mass incarceration, no matter where in history you begin your research—up to and including the present day.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

You can learn more by visiting the Critical and Social History Project’s website.

Using Crime Science to Fight for Wildlife

There is no question that the fashion industry causes great harm to the environment. The industry’s faddish nature, combined with the overproduction of low-cost, low-quality pieces, is designed to encourage overconsumption. Production of fast fashion garments eats up precious resources, like clean water and old-growth forests, and discarded clothing can sit in landfills for hundreds of years, thanks to synthetic materials used in construction.

According to scholars Monique Sosnowski—a Ph.D. candidate in criminal justice at the CUNY Graduate Center—and John Jay Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice Dr. Gohar Petrossian, pollution is not the fashion industry’s only crime. In a new article, they investigated what species were being utilized for the fashion industry, which is worth over $100 billion globally, in order to better understand the damage the industry causes to wildlife and wild places.

Sosnowski and Petrossian looked at items imported by the luxury fashion industry and seized at U.S. borders by regulatory agencies between 2003 and 2013. Their study found that, during that decade, more than 5,600 items incorporating elements illegally derived from protected animal species were seized. The most common wildlife product was reptile skin—from monitor lizards, pythons, and alligators, for the most part—and 58% of confiscated items came from wild-caught species. The authors also found that around 75% of seizures were of products coming from just six countries: Italy, France, Switzerland, Singapore, China and Hong Kong. The heavy involvement of the European countries was unexpected, according to Dr. Petrossian, because they are key players in fashion design and production but “don’t generally come up in broader discussions on wildlife trafficking.”

THE SCIENCE OF WILDLIFE CRIME

The paper applied “crime science, a body of criminological theories that focus on the crime event rather than ‘criminal dispositions,’ to understand and explain crime. The overarching assumption is that crime is an opportunity, and it is highly concentrated in time, as well as across place, among offenders, and victims,” says Dr. Petrossian. Their scientific approach enabled the authors to analyze patterns and concentrations in wildlife crime, which Sosnowski notes is among the four most profitable illegal trades.

“We are currently living in an era that has been coined the ‘sixth mass extinction,’” she says. “It is crucial that we understand the impact that humans are having on wildlife, from habitat loss to the removal of species from global environments. Fashion is one of the major industries consuming wildlife products.”

A background in wildlife conservation, including unique experiences like responding to poaching incidents in Botswana and rehabilitating trafficked cheetahs in Namibia, led Monique Sosnowski to a Ph.D. in criminology; she wanted to move beyond a more traditional conservation-informed approach to address what she’d seen in the field. Working with Dr. Petrossian on a series of studies applying crime science to wildlife crimes has given her a broader view of the effects of wildlife-related crime on global ecosystems.

CREATING SOLUTIONS, SAVING WILDLIFE

Why is it important to understand what species are most commonly used in luxury fashion products, and where they are coming from? A study like this one provides information about trends that policymakers can use to strengthen or focus enforcement and inform better understanding of the issues. Sosnowski calls this “the key to devising more effective prevention policies.”

Currently, global regulation of the trade in wildlife products, including leather, fur, and reptile skin that come from species both protected and not, is the province of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES); this treaty aims to ensure that international trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. But the treaty is limited in scope.

“Given the prevalence of exotic leather and fur in fashion, we believe CITES and other regulatory bodies should enact policies on its use and sustainability in order to protect wild populations, the welfare of farmed and bred populations, and the sustainability of the fashion industry,” Sosnowski says.

Consumers also have a role to play. “We are all led to believe that products found on the shelves are legal, but as this study has demonstrated, that isn’t always the case. Consumers of these products are the ones who have the power to change the behaviors of a $100 billion industry. We need to ask questions about where our products were sourced, and respond accordingly.”

###

Summarized from EcoHealth, Luxury Fashion Wildlife Contraband in the USA, by Monique C. Sosnowski (John Jay College, City University of New York) and Gohar A. Petrossian (John Jay College, City University of New York). Copyright 2020 EcoHealth Alliance.

Podcasting at John Jay: Making Research Accessible

If you’re like us, you love podcasts enough that you’ve subscribed to more than you can listen to in a week of subway commutes. Podcasting, then called online radio, rose in popularity with the proliferation of mp3 players in the early 2000s. In tandem with other personal platforms like blogs, podcasts exemplified the “democratizing spirit” of the internet.

Today, they are big business. Since the release of Serial in 2014, podcasts have boomed. Monthly listeners have nearly doubled since 2014, from around 39 million Americans to an estimated 90 million. As the listening audience grows, quality improves, and bigger names get interested in the medium, advertisers are investing millions.

At John Jay, interest in podcasting has risen along with the medium’s growing potential. The college is home to a variety of podcasts, run by students, faculty and staff, on a rainbow of topics. For example, students in the English department work with Professor Christen Madrazo to write, produce, and edit Life Out Loud, which highlights the diverse voices and real stories of John Jay’s student body. We also have faculty working on podcasts hosted outside John Jay, podcasts run by research centers, and faculty and staff who produce their own shows, right here on campus.

We will introduce you to two homegrown John Jay podcasts that seek to translate scholarship into a form that everyone can understand. Meet Kathleen Collins, a Reference Librarian and Professor at John Jay College, and Nick Rodrigo, a CUNY Ph.D. candidate and John Jay College adjunct professor. While Kathleen is on her 38th episode of podcast Indoor Voices, and Nick has just released the first six episodes of They Are Just Deportees, both share the desire to take CUNY research out of the ivory tower and bring it to the community.

Kathleen Collins has been producing Indoor Voices since the summer of 2017. She started the podcast as “a way to highlight the fascinating things going on around CUNY that might not be widely known. There are so many inhabitants in the CUNYverse doing incredibly interesting things… We like being able to provide a low-stakes, easy-to-share platform for people to talk about their work.”

Kathleen Collins has been producing Indoor Voices since the summer of 2017. She started the podcast as “a way to highlight the fascinating things going on around CUNY that might not be widely known. There are so many inhabitants in the CUNYverse doing incredibly interesting things… We like being able to provide a low-stakes, easy-to-share platform for people to talk about their work.”

To Kathleen, the conversations are the key element. She and her co-host, La Guardia Community College librarian Steven Ovadia, interview CUNY faculty, students, alumni and staff members about their research or creative output; they have a great deal of leeway to highlight what interests them.

Nick Rodrigo is new to podcasting, overcoming challenges as he meets them in the course of creating They Are Just Deportees. The newly-launched show examines the various ways in which the U.S. immigration enforcement system shapes and controls the lives of migrant communities in this country. With co-host Darializa Avila Chevalier, TAJD helps listeners to understand “the multiple sites of border enforcement in the U.S., and the punitive effects of the country’s periodic moral panics on the ‘criminal alien.'”

Nick Rodrigo is new to podcasting, overcoming challenges as he meets them in the course of creating They Are Just Deportees. The newly-launched show examines the various ways in which the U.S. immigration enforcement system shapes and controls the lives of migrant communities in this country. With co-host Darializa Avila Chevalier, TAJD helps listeners to understand “the multiple sites of border enforcement in the U.S., and the punitive effects of the country’s periodic moral panics on the ‘criminal alien.'”

Nick, and his associates in the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime Working Group (the sponsor of the podcast), think this is a particularly relevant topic. “Immigrant rights have come under increasing threat from the state, with bans on immigration from Muslim majority countries, the detention of children at the U.S./Mexico border, and the pledge of this administration to increase the forced removal of all undocumented people. … It is vitally important that the deportation system — which expels up to 300,000 persons a year — be placed in the historical context of this country’s treatment of the ‘other,’ while focusing on the real time implications of the current system on immigrant communities.”

For both showrunners, podcasting is a great way to make sometimes-complex issues and scholarship more accessible to an average listener. Says Nick, “two of the major issues in scholarship today are the ‘ivory tower’ mentality of academics and a lack of interdisciplinary focus on major social issues. Conferences and public lectures can be delivered in such inaccessible language that they can be alienating to non-academics. Podcasting allows for the complex issues concerning immigration enforcement to be distilled and presented to the public in a way that is accessible and digestible, with the opportunity for the listener to pause, reflect, and reengage at their own pace. Podcasting also provides a platform for criminologists, sociologists, public health experts, geographers, and journalists to come together on an issue and, if the interview structure is good, a compelling narrative for change can be constructed.”

Kathleen also wants to make it easier for non-experts to engage with what CUNY produces. “There is so much going on within CUNY,” she says, “and it shouldn’t be hidden inside the academy. Podcasts are a good way to get people interested in new things — it’s a mini, portable seminar for your ears. But since Steve and I act as generalists in our role as interviewers, we can hopefully elicit a layman’s interpretation of what scholars are thinking and writing about. The point is to bring attention to the author or artist, and ask about their research and writing process and teaching — these topics bring the conversation to a universal level.”

Creating content to fit the platform can sometimes be challenging. Nick was “forced to learn new skills on the job,” but found that his struggles with editing gradually turned into confidence! Kathleen cites the extensive support and inspiration from other podcasters and staff at the college as a source of her success and joy in creating Indoor Voices.

In the end, she says she loves every episode she produces — thanks to the satisfying conversations and intimate connections she can form with guests during a 40 minute interview, each new episode supplants the last as her new favorite.

Check out the latest episodes of Indoor Voices, They Are Just Deportees, and more John Jay podcasts:

- Indoor Voices: J Journal founders Adam Berlin and Jeffrey Heiman have been producing the literary magazine for twelve years. The high quality creative work they feature deals with contemporary justice issues, but not always in a way you might expect.

- They Are Just Deportees: You can find the first six episodes on the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime website, or by searching on Spotify.

- Reentry Radio: The latest episode of the podcast produced by John Jay’s Prisoner Reentry Institute deals with employment discrimination against justice-involved individuals, with special guest Melissa Ader of the Legal Aid Society’s Worker Justice Project.

- This World of Humans: Host Nathan Lents talks to Hunter College researcher Dr. Jill Bargonetti about using mouse models to study triple-negative breast cancer.

Policies Changing New York: Impact Magazine 2018-19

As a New York institution and part of the City University of New York, John Jay College is home to many who want to drive real-world reform to make New York communities stronger. Our unique research centers provide evidence-based partnerships and guidance that city officials and state legislators need to create better policy. Read on for a quick look at the impactful work they are doing in New York, or read the full story in our latest issue of Impact research magazine.

Easing Reentry

The Prisoner Reentry Institute has been a research center since 2005, when it was founded to help people live successfully in their communities after contact with the criminal justice system. The center, directed by Ann Jacobs, engages in a combination of public advocacy, direct service, and collaborative partnerships to promote a range of reentry practices, with a focus on creating pathways from justice involvement to education and career advancement.

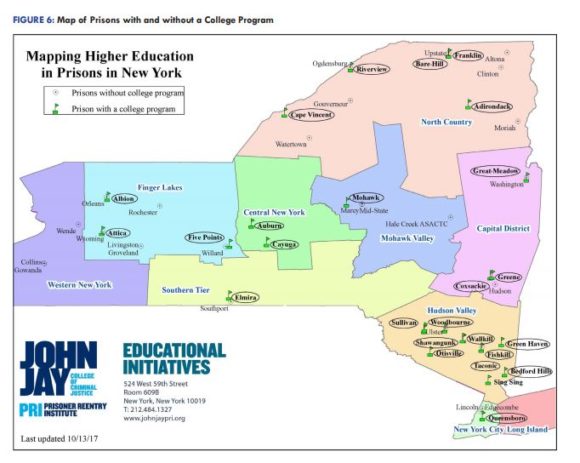

In pursuit of that goal, PRI advocates for higher education in prisons, priming what they call the “prison-to-college pipeline.” They recently produced a report mapping higher education opportunities in New York State prisons, finding that only 3% of more than 45,000 people in New York prisons were participating in higher education programs, despite expanded funding.

PRI is also interested in post-incarceration advocacy. A work group, led by PRI’s Director of Public Policy Alison Wilkey and comprised of local stakeholders, is working to change the New York City Housing Authority’s policies excluding residents who have been arrested. The work group’s actions, including the creation of a clearer exemption application, new guidelines limiting the use of exclusions, and tenant education, have helped reduce the number of people excluded from NYCHA housing 50% from 2016 to 2018.

Interrupting Crime

A team of Research and Evaluation Center researchers is evaluating Cure Violence, a public health approach to violence reduction.The program relies on neighborhood-based workers, often with a history of justice involvement, mediating and working with younger people in the neighborhood to keep them from going down a violent path.

“Politically, it’s a difficult program to operate,” says REC Director Jeff Butts, because city officials are often wary of Cure Violence workers’ criminal histories. But REC has found that Cure Violence sites in the South Bronx and Brooklyn have seen greater violence reductions than comparison sites. According to Butts, explaining the research and the results clearly to the public is key to shifting policy. “You can’t change policy, no matter how smart you are, just by publishing articles in academic journals.”

Less Punishment, Less Crime

Violence isn’t the only type of crime that can be reduced with less punitive solutions. Director of research project From Punishment to Public Health (P2PH) Jeff Coots holds that alternatives to incarceration can not only reduce the use of prison and jail terms, but also offer rehabilitative services to people in need. “Punishment alone is not getting us the public safety outcomes we want,” he says. “How do we identify public health-style solutions that can respond where punishment does not, and isolation will not?”

Among P2PH’s signature initiatives is a pilot project to use pre-arrest diversion for minor offenses committed by the homeless. Many of those cases were previously decided at arraignment, denying arrestees the chance to connect with needed services. The pilot has reduced the number of people arrested and increased the number connected with services like transitional housing and health treatment.

In general, Coots believes policymakers are increasingly open to health interventions as an alternative to incarceration. “We don’t want the jail to be the biggest mental health provider in our community.”

Justice by the Numbers

The Data Collaborative for Justice is invested in documenting the scale of the criminal justice footprint, in New York and a network of other cities, and

considering solutions to reduce it. DCJ explores high-contact points in the system, including pretrial detention and incarceration in New York City jails. A major project for the center has been to produce an evaluation of the 2016 Criminal Justice Reform Act, passed by the New York City Council to “create more proportional penalties for certain low-level, nonviolent offenses.” With support from the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, DCJ’s evaluation shows that the CJRA seems to be achieving its aims — 90% of summonses for five high-volume offenses like noise violations and littering are now civil rather than criminal, with an associated decline in criminal warrants.

The positive impact of this legislation has the potential to push policy change in other areas by informing conversations with lawmakers. DCJ works closely with city and state agencies to gather data and make it available to policymakers so they have the resources to make evidence-based decisions. “Policy neutrality is an important part of DCJ’s mission and outlook,” says Project Director Kerry Mulligan. “That has allowed us to be a trusted broker with a diverse set of data partners.”

Among John Jay College’s research centers and projects, some researchers are building the evidence base, while others are rolling up their sleeves to help cities implement and evaluate solutions on the ground. In each case, the vital goal is making communities safer. Says REC’s Jeff Butts, “You have to put the evidence in front of [policymakers] on a regular basis in order to get the political culture to start to shift.”

For the full feature, please visit the John Jay Faculty and Staff Research page to read the whole magazine in PDF form!

Bringing Justice Back to the System: Impact Magazine 2018-19

Although it may seem obvious, the basic question of fairness is of huge concern to those interested in reforming our nation’s criminal justice system. This is especially important in the courtroom. “The administration of justice,” says John Jay constitutional law professor Gloria Browne-Marshall, “is supposed to be done as equally under the law as possible.” That’s the concept of due process.

But the system doesn’t always work fairly. “Mass incarceration … is unfortunately disproportionately shouldered by people of color,” said Browne-Marshall. So how do we change things to ensure equitable outcomes?

Behind the scenes, a host of scholars at John Jay College are leading the charge to develop findings, share knowledge, and train officers of the court to promote courtroom practices that are more impartial and lead to real justice. Read on to be introduced to these scholars, or read the full feature article on pages 16-17 of this year’s Impact research magazine.

Taking Better Testimony

Young or old, witnesses can be unreliable. “The most important finding is that memory is malleable and reconstructive, rather than an exact replica of any given event,” said Deryn Strange, a professor of psychology. Adult memories, especially when recounting traumatic experiences, can change over time and with the introduction of new information. Memories may incorporate intrusive thoughts, or even warp to include what the individual wishes she did differently.

Strange, who not only does research on memory but also educates courtroom officials, believes that whenever someone’s memory is on trial, judges, juries and lawyers all need to understand the power and limitations of human memory. Otherwise, decisions of guilt or innocence may very well be incorrect and unjust.

Kelly McWilliams, an assistant professor in psychology, focuses her research on children in the witness box, specifically how they use and understand language, and experience memory. Children’s memories are more limited than adults’, and they are susceptible to the introduction of false memories through questioning. Gaining helpful testimony from young witnesses depends more on the questions asked than on their abilities.

Kelly McWilliams, an assistant professor in psychology, focuses her research on children in the witness box, specifically how they use and understand language, and experience memory. Children’s memories are more limited than adults’, and they are susceptible to the introduction of false memories through questioning. Gaining helpful testimony from young witnesses depends more on the questions asked than on their abilities.

McWilliams’s research builds on recommendations from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development — like asking open-ended questions, using general prompts, and more. McWilliams tests new modes of questioning to gather details children might not share in response to an open-ended question, which may be necessary for charging decisions or establishing credibility. “These are practices that take into account what kids are capable of doing and what we should and shouldn’t be asking them to do as witnesses,” she says.

Understanding the Science

Courtroom participants — attorneys, judges, and jurors alike — can often use help determining which pieces of scientific evidence are credible.  Margaret Bull Kovera, a social psychologist by training, has researched this issue for two decades.

Margaret Bull Kovera, a social psychologist by training, has researched this issue for two decades.

Evidence like repressed memories and bite analysis, and even fingerprint evidence, lack a solid basis in science. However, they often make their way into evidence, accompanied by expert witnesses, and parties to a trial may not know enough to challenge them. As a result, “they make decisions that are really not borne out by the evidence, if one were evaluating it properly,” says Kovera.

Kovera’s research is working toward a set of safeguards that contribute to better decision-making. The most promising method is simply to highlight flaws in the evidence during cross examination — something that attorneys can be trained to do — or opposing experts can help provide context. In the end, procedure that relies on solid science helps result in fairer justice.

Open to Interpretation

The quest for fairness doesn’t end at conviction. Post-incarceration, language access is an important part of accessing necessary services and treatment in prison. According to Aída Martínez-Gómez, an associate professor of legal translation and interpreting, incarcerated people who don’t speak the official language of the institution where they are being held face a number of roadblocks. It’s harder for incarcerated people to navigate forms, requests, and services without translated materials. But she says there are promising solutions.

The quest for fairness doesn’t end at conviction. Post-incarceration, language access is an important part of accessing necessary services and treatment in prison. According to Aída Martínez-Gómez, an associate professor of legal translation and interpreting, incarcerated people who don’t speak the official language of the institution where they are being held face a number of roadblocks. It’s harder for incarcerated people to navigate forms, requests, and services without translated materials. But she says there are promising solutions.

Martínez-Gómez advocates most strongly for nonprofessional interpreting services — or services provided by incarcerated peers. In one example from her work, the practice “not only contributed to overcoming the language barrier in the prison, but also to specific rehabilitation goals and potential job opportunities” once the individual’s sentence ended.

In the end, creating a fairer system means using empirical evidence to apply justice accurately and equally in the courtroom and beyond, and to avoid administering justice in arbitrary, capricious, or discriminatory ways. Though these studies can’t solve every inequality, small changes in process and better education of the parties involved can move the needle on basic fairness.

For the full feature, please visit the John Jay Faculty and Staff Research page to read the whole magazine in PDF form!

A Legacy of Violence: Impact Magazine 2018-19

In American politics, issues like immigration and the refugee crisis generate national headlines daily. But the complex dynamics of immigration are inextricably tied to U.S. history in the Americas, where a legacy of colonialism continues to define the relationship between the United States and the nations of Central and South America.

More than 50 years of interventions in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Panama, Chile, Brazil and other countries in the southern hemisphere have affected the lives of these countries’ residents in various ways. Many have resulted over the long term in the systematic destabilization of government coupled with a legacy of violence and military dictatorship, contributing to the reasons that immigrants may cite for wanting or needing to leave their homelands: gang violence, repression, dictatorship and more.

Several professors and students at John Jay have made it their life’s work to investigate the causes and ramifications of this instability, among them José Luis Morín, Claudia Calirman, Pamela Ruiz, and Marcia Esparza. We profiled these scholars in our latest issue of Impact magazine. Read on for a summary of our Impact feature story.

Suing for Justice

José Luis Morín, Chair of John Jay’s Latin American and Latinx Studies Department, is deeply involved with the process of finding justice for the victims of the American 1989 invasion of Panama. Morín had been in the thick of the invasion, which he recalls as “literally a war zone,” and subsequently filed a lawsuit on behalf of individuals who had been directly harmed, seeking reparations from the United States.

José Luis Morín, Chair of John Jay’s Latin American and Latinx Studies Department, is deeply involved with the process of finding justice for the victims of the American 1989 invasion of Panama. Morín had been in the thick of the invasion, which he recalls as “literally a war zone,” and subsequently filed a lawsuit on behalf of individuals who had been directly harmed, seeking reparations from the United States.

Nearly 30 years later, in December 2018, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights finally issued a decision in the case, holding the U.S. government solely responsible for the deaths of Panamanian citizens during the invasion; it is responsible for compensating the victims for damages.

Finally having a decision saying that the U.S. had violated human rights through its actions was a key step toward justice. Morín returned to Panama following the decision, going to communities to explain what this meant and speak to the individuals and families who were part of the case.

“What makes this particularly relevant, and so critical to the work we do in this department, is having our students learn about the history of Latin America and how the U.S. played such an integral role in how these countries developed,” said Morín.

Art Under Fire

The U.S. justified its intervention in Panama as a defense of democracy, but some U.S.-backed “democratic” leaders have turned out to be authoritarian dictators. This was the case in Brazil, where a right-wing authoritarian government ruled from 1964 to 1985.

Claudia Calirman, Associate Professor of Art & Music, is an expert on artistic resistance to government repression in Brazil, and her research — including her first book, Brazilian Art Under Dictatorship — explores how art was expressed in mediums designed to thwart detection. These mediums include body art and what was called “ready mades,” which are every day objects modified to carry subversive or critical messages that could be circulated publicly without implicating the artist.

Claudia Calirman, Associate Professor of Art & Music, is an expert on artistic resistance to government repression in Brazil, and her research — including her first book, Brazilian Art Under Dictatorship — explores how art was expressed in mediums designed to thwart detection. These mediums include body art and what was called “ready mades,” which are every day objects modified to carry subversive or critical messages that could be circulated publicly without implicating the artist.

Calirman’s ongoing work explores different facets of Brazilian art over a variety of time periods, showcasing the ways Brazilian artists approach tough issues and combat repression. Her forthcoming book deals with Brazilian women’s struggles with the term “feminism” as it has applied to their work since the 1960s and ’70s. And Calirman is working on curating a Spring 2020 exhibit at John Jay’s Shiva Gallery about ongoing censorship of art in Brazil.

periods, showcasing the ways Brazilian artists approach tough issues and combat repression. Her forthcoming book deals with Brazilian women’s struggles with the term “feminism” as it has applied to their work since the 1960s and ’70s. And Calirman is working on curating a Spring 2020 exhibit at John Jay’s Shiva Gallery about ongoing censorship of art in Brazil.

Uncovering Violence

Pamela Ruiz is a recent graduate of the CUNY Criminal  Justice doctoral program whose dissertation analyzed the evolution of gang violence in the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. An explosion of gang violence in these Central American countries is connected to instability and the destabilization of democratic governments.

Justice doctoral program whose dissertation analyzed the evolution of gang violence in the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. An explosion of gang violence in these Central American countries is connected to instability and the destabilization of democratic governments.

Ruiz aimed to classify violence that is truly gang-associated, to dispel myths around violence and better target enforcement. “The perception is that all this violence is attributed to gangs,” she explained, ‘but when you go into a country and interview people, you discover that it’s different groups contributing to violence in different areas.”

Her quantitative methods are filling a key gap in research in the region, providing reliable data that policymakers can use to reduce violence, target corruption, and more.

Documenting Dictatorship

Marcia Esparza, Associate Professor of Sociology and an expert on genocide, state crimes, and human rights violations, would argue that, wherever violence and repression are to be found, remembering victims and commemorating resistance is vital in learning from the past and addressing present violence and corruption.

“If we don’t look at the long-term footprints of militarization on the local level, we cannot talk about democracy or democratic institutions,” she says. Esparza was inspired by her work interviewing genocide survivors in Guatemala to found the Historical Memory Project, which archives and draws on primary sources to memorialize the victims of genocide and state violence, and those who resisted it.

She also emphasizes the importance of helping John Jay students connect with their histories as part of a diaspora. Esparza’s students play a key role in the project’s efforts, as they organize and sort through the large archive to pull together educational exhibitions.

Shared History

The shared history of interventionist foreign policy and authoritarian rule has created a spider’s web of mutual entanglements that continue to tie the United States to its southern neighbors to this day. This long-term history of invasion and intervention by the United States has created patterns and threads that John Jay scholars trace in their efforts to understand, alleviate, and memorialize violence and instability in these countries, in order to achieve justice, create a lasting peace and, in the process, help some Latinx John Jay students better understand their own histories.

For the full feature, please visit the John Jay Faculty and Staff Research page to read the whole magazine in PDF form!

Denise Thompson is Trying to Make Post-Disaster Rebuilding Better

Denise Thompson is an Associate Professor in John Jay College’s Department of Public Management, and an expert on disaster management and risk reduction. Her new book, Disaster Risk Governance: Four Cases from Developing Countries, was published in July 2019 by Routledge. To learn more about where and how she does this work, you can read a profile of Dr. Thompson in this year’s Impact magazine.

Denise Thompson is an Associate Professor in John Jay College’s Department of Public Management, and an expert on disaster management and risk reduction. Her new book, Disaster Risk Governance: Four Cases from Developing Countries, was published in July 2019 by Routledge. To learn more about where and how she does this work, you can read a profile of Dr. Thompson in this year’s Impact magazine.

Read on for an edited interview with Dr. Thompson about her work related to disaster planning and recovery, and how she approached writing a book on such a complex topic:

What factors are most important to consider when planning for storms or natural disasters, whether far in the future or imminent?

Maybe the best way to answer that is to look at the disaster cycle. Mitigation, planning preparedness, response, recovery, reconstruction, and then back to mitigation. Even though I put the phases into discrete components, the cycle is integrated, not discrete. And the steps must always be revised.

Mitigation is essentially putting structural and non-structural elements in place well ahead of a storm. That includes hardening infrastructure as well as putting systems in place to make sure we can respond.

The preparedness phase gets ready for imminent disaster, including by bringing together supplies, people and other resources to respond, and making sure supplies are prepositioned where they’re expected to be needed; organizing transportation and marking routes for evacuation; and more.

Recovery includes the immediate response post-disaster, where communities plan for building or rebuilding; get schools, offices, child care and other systems back up that are required for day-to-day functioning; and bring critical services back on line, like roads, food supplies, water, and the government.

Finally, reconstruction is a process of longer-term rebuilding. Ideally, this includes innovation to ensure communities are “building back better,” and is an extremely integrated, wide-spectrum process that moves toward hardened infrastructure and sustainable processes. This happens after an assessment is done of the damage, and must be integrated into planning.

One example is in the Bahamas. Because they are unable to rebuild exactly the same as before the storm hit, the government is thinking about putting some infrastructure underground, like communication towers, to create some protection from the next storm.

How do you factor in climate change when considering ongoing efforts to prepare for and recover from natural disasters?

Well, what is a disaster? We have to think about that. I was listening to a story on NPR, the bird population of the U.S. shrank by one billion birds – that’s climate change. And even epidemics. Certain bacteria and invasive species thrive in certain temperatures. So it’s a disruption, not only of the human ecosystem, but also of the animal ecosystem.

When we talk about disasters, we tend to talk about natural disasters, but it’s so much bigger. We’re not even talking about man-made disasters, like terrorism or cyberattacks, which could be catastrophic. Those are disasters, too, but man-made.

Given the trends in natural disasters associated with climate change (e.g., hurricanes and tropical storms are more frequent, and more frequently of record intensity levels), are there places that are becoming unlivable, or that should be abandoned?

Yes, there are places that should be abandoned. A lot of these countries, their populations are concentrated along the coast, and there are vulnerabilities. Like schools that are flooded in every single storm of course should not have been built where they are.

Are issues of rebuilding and relocation tied in with race and class?

These issues are very tied to rebuilding in many places. You can also look at a place like Flint – race, class and vulnerability are interlinked. Or Newark. Usually, African Americans, Latinos and other minorities are more vulnerable to these disasters. And it’s harder for the poorest communities to recover – the same event has a more drastic impact. The rich have more resources.

In island states, the line is more blurred. The interiors are more rugged, which means most people tend to locate along the coastline, so it’s not as clear-cut an issue as in, say, Hurricane Katrina. But there’s an issue of moral hazard; even knowing that it’s dangerous, people build anyway, knowing that somebody will help them to rebuild. Like the government, or insurance money. So people tend not to bother to plan for disasters.

However, organizations have been exploring insurance, like livelihood protection, for poorer people. For example, the Caribbean Catastrophic Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) pools resources from many countries in the region, who pay into this fund. They are disbursed to governments directly, to help pay for rebuilding. Commercial facilities might be getting out of disaster insurance, but others are stepping into that void.

Is there an ideal balance between recovery efforts provided by home governments versus outside aid?

I don’t know if there’s an ideal balance. Governments operate at different levels – national, regional, local, community, household – so we usually say that the government closest to the people should be equipped to help them. But what we find is that often the governments closest to the people are themselves incapacitated by whatever event took place, and they’re not able to help. And if you go one level higher, they may be able to help in some ways but not others, and so on. In cases like those, outside help is needed; the quantity depends on the issue.

Is there a useful role for individual aid?

There’s a useful role, but it’s hard to manage spontaneous volunteers. They may put themselves in harm’s way. Typically we say, go through an entity to help. Most agencies right now want money, because they can best divert it to where it’s needed. That may be potable water, or a sanitary facility, or helping women or children get out of situations where they’re more vulnerable thanks to the disaster. It may be a number of things.

When you talk about disaster planning, mitigation, risk reduction, it’s a big, involved process, and very complex. It’s hard to get a handle on it, but agencies do it. Their effectiveness depends on resources. And no one place has the level of resources needed. That’s why governance systems are important, to bring all these things together – the resources, money, people, institutions, laws, and the formal and informal arrangements that must be made to keep people safe.

This is obviously a vastly complex topic that touches on every area you can imagine. How do you write a book about that? Is your book more broad, or is it more of a tool?

This is obviously a vastly complex topic that touches on every area you can imagine. How do you write a book about that? Is your book more broad, or is it more of a tool?

The idea for the book came when I was doing a lot of work in the Caribbean and seeing a lot of money being spent, with a minimal return on investment. When the next event came, we were still dealing with the same issues. Activities were happening piecemeal, done by aid agencies, governments, the UN. And preexisting factors, like colonialism, undermined institutions. These were antecedents to what we’re seeing now, but we never could put them together, because we’re always trying to put out fires.

Disaster management systems happen in context of the country, and I realized that countries with weaker governance systems also have weaker disaster management systems. Governance is an umbrella term, comprising all the institutions, systems, actors and processes that come together around disasters.

So what I wanted to do was come up with a number of variables we could use to pinpoint areas we could shore up to improve disaster risk reduction and outcomes. I looked at institutions as a key component in that, like legislation, insurance, security. I also talked about labor policy, networks, economic investment – all these things may not be part of disaster policy, but they support it.

Why did you pick those four specific countries – two in the Caribbean, two in Sub-Saharan Africa – to feature in your book? Did you find some similarities there?

When I came into academia in 2008, there wasn’t much literature on poor countries. And that is not specific to disaster management. The voice was missing. I thought, if I looked at the sub-Sahara and the Caribbean, I would be better able to come up with a governance framework that actually works for developing or poorer countries.

The similarities I picked up are mostly in the institutional and informal aspects. For instance, indigenous peoples from the Caribbean and from Africa were similar in that they had communities with their own laws and customs that may be opposed to planning around disasters. Also, these countries have a legacy of corruption – not all poor countries, some rich countries have higher rates of corruption – but still, government ineffectiveness, government inaccessibility to their populations, these things were comparable. Those cause inefficiencies and waste in the system, they cause people to take longer to recover from disasters. It’s complex and messy.

In the book you have to try to manage the multiple components; you can’t write on everything but you can pick out the salient things. I hope that’s what I was able to do.

Is it disheartening, to see inefficiencies and to see problems getting larger every year, problems that we’ve caused ourselves and failed to find effective solutions to thus far?

Yes, but at the same time, we’re working more closely with communities, and households and individuals, and I think that’s where it has to happen. So while governments create the policies, the infrastructure and the systems, the ecosystem is bigger, with subsystems within it. If you work at the micro level, you can shore up the entire system.

In the Caribbean and in Africa, there are regional agencies that are the real workhorses and innovators – the East African Commission, the African Union, Caribbean Disaster and Emergency Management System, CARICOM. CCRIF, for example, is one of the first in the world to push for countries to pool their resources. Other regions, like Southeast Asia, are doing a similar thing. All of these groups come together to actually build and pilot things.

Gerald Markowitz shines light on corporate bad behavior

Distinguished Professor of History Gerald Markowitz and long-time writing partner David Rosner, a Professor of Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia University, have been researching industrial pollution and contaminants since the early 1970s. Their first jointly-authored book, Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease in Twentieth-Century America, explored historical evidence of the lung disease silicosis, which is a hardening of the lungs due to inhaling dust found in sand or rock. Thanks to Deadly Dust, Markowitz and Rosner came to the attention of lawyers bringing workplace safety suits on behalf of construction workers suffering from silicosis, launching a long career of research and expert testimony on occupational disease and toxic substances. In the early 2010s, the duo began an investigation into asbestos and asbestos-related disease.

Their work turned up hundreds of articles on the dangers of asbestos, now a watchword for poisons that can lurk in our homes, dating from 1898 to the present. Markowitz and Rosner also referred to corporate records and documents made public through court discovery; a more recent project called ToxicDocs is an open-source, online database of more than 15 million pages of documents related to silica, lead, vinyl chloride, and asbestos that were previously not easily accessible.

Their work turned up hundreds of articles on the dangers of asbestos, now a watchword for poisons that can lurk in our homes, dating from 1898 to the present. Markowitz and Rosner also referred to corporate records and documents made public through court discovery; a more recent project called ToxicDocs is an open-source, online database of more than 15 million pages of documents related to silica, lead, vinyl chloride, and asbestos that were previously not easily accessible.

In June, Markowitz’s expertise was featured prominently in the American Journal of Public Health, in an article detailing a representative episode in the history of the struggle between industry and regulators. In “Nondetected: The Politics of Measurement of Asbestos in Talc, 1971-1976,” Markowitz and his co-authors describe the years-long interval between the talc industry’s acknowledgement that asbestos is toxic and their taking action to protect consumers, and the subsequent conflict between the Conflict, Toiletry, and Fragrance Association (CTFA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) over regulating appropriate methods for detecting asbestos contamination in consumer talc products and setting safety standards.

The focus of the article, said Professor Markowitz, “was that the cosmetic industry, I think very consciously, used this concept of nondetected, which we as consumers think of as ‘no asbestos in the talc,’ but nondetected could mean enough asbestos in the talc to cause disease. And that’s what the industry understood, but consumers did not.”

The CTFA’s 1970s victory in lowering detection standards and advocating for self-regulation is still bearing fruit; recent lawsuits against talcum powder manufacturers allege the household product causes cancer due to asbestos contamination. As recently as 2018, courts awarded plaintiffs record damages of close to $4.7 billion in a case against manufacturers, capturing public attention.

We sat down with Professor Markowitz to talk about his work researching industrial poisons and about corporate responsibility to the consumer in today’s world. Read on to hear from Professor Gerald Markowitz in his own words.

Why do you believe that talc product manufacturers continued to accept a lower standard for asbestos eradication despite known health dangers, not to mention the risks of litigation?

When they developed this idea, in the 1970s, their basic argument was that there should be as little federal regulation as possible. [The CTFA] was able to lobby the federal FDA that the technologies that the FDA was proposing were not able to be completely accurate, would give too many false positives, would take a long time to do, and would be costly. So they proposed their own method. And they’re able to eventually convince the FDA that it should not be federal but industry regulation.

But what they admit privately is that their method, which is not as demanding as the FDA’s proposed method, was not necessarily accurate and was not necessarily consistent. So to a certain extent, they were really able to forestall regulation by claiming that they could do as good a job [of detecting asbestos in talc products], even though they themselves admitted that they could not do as good a job. And by the very nature of their method, they were going to uncover much less asbestos than the FDA’s method was capable of uncovering.

Do you think there’s something special about the current moment that made this article of particular relevance?

I think it was the variety of ways that deregulation has had an impact on the health and welfare of people in the United States and other parts of the world. To the extent that these articles could help to call attention to that happening, they are important. The advantage of history is that we are able to really see the process unfold in a kind of detail that we don’t necessarily have in observing regulatory of anti-regulatory actions taking place at the moment we’re living in. That level of detail I think is instructive in terms of being able to understand how similar things could be happening today.

Would you like to see this history galvanize some kind of action?

The most important thing that can happen is that people really have to take politics seriously. The United States has a long history of mass movements really demanding and achieving fundamental reforms. Just going back to the 1960s, the demand for civil rights, the efforts of people to get voting rights for African Americans, that didn’t happen simply because Congress decided to pass a law; people were demanding it in mass actions. These are really instructive in terms of what can happen today, and even what is happening today.

Pieces accompanying your article in the AJPH, such as the one by former Assistant Secretary of Labor for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration David Michaels, suggest that corporate influence is getting stronger, to the detriment of consumer and public health. The current administration has loosened or degraded regulatory standards for a variety of products — should we expect more legal battles down the line?

Yes, absolutely. Since the 1970s there has been a very sustained effort by many businesses to oppose regulation, and you get the classic statement by Ronald Reagan, when he said that ‘government isn’t the solution, government is the problem.’ I think the legacy of that, of the push for deregulation as a means of stimulating the economy and freeing business to innovate and all of those kinds of ideas, I think the legacy of that is going to be a variety of problems, not only in consumer products but in environmental damage. It’s going to be for workers, for consumers, for people living in communities where toxic substances are going to be released, we’re going to be suffering those consequences, and the unfortunate thing is that it’s only going to be remedied in retrospect.

And to add one other element, we know that the burden, especially of environmental pollution, toxic waste, global warming, is going to affect poor communities and communities of color to a much great extent than richer communities. At a college emphasizing social justice, this becomes an even more vital issue.

Are there other consumer products known to include dangerous adulterants that are similarly being ‘underregulated?’

BPA [bisphenol A, a chemical used to make certain plastics since the 1960s] is one example; a lot of household cleaners and flame retardants are another one. We’ve discovered that flame retardants are extremely dangerous to people, and that people have them in their bodies. Formaldehyde is another one; there was a scandal about formaldehyde in temporary housing given to people after Katrina, that was unsafe.

There are lots of things we have clues about, but the real scandal is that chemicals are being produced and we’re using them in very large quantities, that have never been tested. And in the United States we have this philosophy, innocent until proven guilty. It’s the same philosophy with chemicals — they are innocent until proven guilty. The Europeans have a system, chemicals can’t be introduced until they’re proven safe. It’s a basic difference in philosophy that companies need to prove that something is safe before they can experiment on us and ensure it doesn’t cause cancer. But in the United States they say that if it does cause cancer, we’ll take it off the market, but that’s very difficult to prove and you’ve done the damage already.

You note in your article that talc researchers were disappointed when their work became known to the industry, but that ‘nothing was done until the results became public.’ Do you think it remains true in cases of corporate wrongdoing that nothing is done until the public finds out all the information?

In the 1970s, there was this wonderful act passed called the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). The fundamental principle behind that was that if you shine the light of publicity and information and people have that, then they have the ability to act in their own interests. One contribution that historians can make is, using the older historical records, we can cast a light on activities and attitudes and actions that permit people to see what is going on and demand change.

Gerald Markowitz is a Distinguished Professor of History in the Interdisciplinary Studies Department at John Jay College and the Graduate Center of CUNY. His research focuses on the history of public health in the 20th century, environmental health, and occupational safety and health. He has authored a number of books, most recently Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of America’s Children, also in cooperation with David Rosner.

Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

Recent Comments