Home » Posts tagged 'John Jay Research'

Tag Archives: John Jay Research

Q&A: Provost Allison Pease Shares her Vision for Academic Excellence and Research

As Dr. Allison Pease embarks on her new role as Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, she brings nearly three decades of commitment to the institution. Dr. Pease is ready to shape John Jay’s academic future from her beginnings as a Professor of English to taking on multiple leadership positions. She will steer the institution’s educational mission in close partnership with President Karol Mason while remaining firmly committed to its core values. As a seasoned academic leader and scholar, Dr. Pease paints a compelling vision for the future of John Jay College. Her vision strongly emphasizes student success, academic excellence, and a vibrant research culture. She is driven by the belief that interdisciplinary collaboration and strong mentorship are the keys to fostering an empowered community of faculty, staff, and students who can achieve their full potential. In an engaging Q&A conversation with the Office for the Advancement of Research (OAR), Dr. Pease outlines her strategic priorities and bold vision of expanding opportunities for all college community members. She discusses her plans to strengthen interdisciplinary collaboration and mentorship, setting the stage for John Jay’s next phase of growth and innovation.

Introduction

Hi, I’m Alison Pease. I’m the Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs. I have been at John Jay for 27 years, first starting out as a professor in the English department,taking on a series of different roles, including the director of gender studies, the chair of English, the Interim dean of undergraduate studies, a few administrative roles in the provost’s office, and eventually, I am now here as provost.

Q: What personal and professional aspirations do you have for your tenure as Provost?

Dr. Pease: I’m excited to be the provost of John Jay. It’s an honor. And John Jay, to me, has always been a place of opportunity and transformation. That’s what the college experience was about. But as a professor and then an administrator, it’s been a place that’s given me a lot of opportunity. I want that for all of our students. I want that for our faculty and our staff. And so, the opportunity personally to get to lead Academic Affairs is just a real honor, but professionally, I want to make sure that everybody has these kinds of opportunities.

Q: What key priorities will guide your leadership, and how do you plan to steer the academic community toward the future you envision for John Jay College?

Dr. Pease: I have three priorities. I want to focus on student success. I want to focus on academic excellence and then administrative excellence and support, starting with student success. We have done a great job in improving student success at John Jay, and we have some more work to do. So, the next steps are on creating an undergraduate foundational program where students really understand that they belong to a smaller community, that they have opportunities to thrive and explore their careers, and that we are improving the educational experience with them. Then, when it comes to academic excellence, this is sort of where faculty and students meet, right? So, it’s about hiring just the best faculty that we can and providing a rigorous curriculum. How am I going to achieve these two things, academic excellence and student success, through administrative excellence and support? And so, the key here is investing in faculty and staff professional development and in our research enterprise so that we can continue to grow and enhance the and enhance experience of everybody on campus, faculty, staff, and students alike.

Q: How do you intend to foster and support faculty research across diverse disciplines, particularly in creating an environment that champions interdisciplinary collaboration and intellectual exploration?

Dr. Pease: John Jay is already a research powerhouse, and my job as provost is to really tell our research story. We have the most productive faculty in terms of producing research per year in all of CUNY, and we’re the third largest grant- and grant-funded institution in CUNY. We continue to get better and support faculty by listening to what faculty need and figuring out how to reach them better. I’m really proud of our office for the advancement of research, for the work that they do in reaching out to individual faculty and smaller groups of faculties, and also for thinking interdisciplinarily by creating clusters and knowledge clusters and ways that we can continue to advance our research mission.

Q: What are some of your scholarly achievements that you are most proud of?

Dr. Pease: If I’m being honest, I’m proud of a lot of my research, but the work I’m most proud of is a book I published almost 20 years ago. It’s called Modernism, Mass Culture and the Aesthetics of Obscenity. It is a very rigorous cultural and Aesthetic history and analysis of the relationship between, believe it or not, art and pornography from the 18th century to the 20th century. What I’m proud about in that work is that it ended up defining a field. And, you know, the book is still in print, 25 years later, it’s still cited, and it established my way of interacting in the modernist studies field.

Q: How do you plan to balance the demands of high-level administration with ongoing scholarship? Do you see opportunities to integrate your scholarship into your work as Provost?

Dr. Pease: It is an honor and a privilege to be the provost of a big institution like John Jay, and I see that as my absolute priority. My own research takes a real back seat. I’m not spending a lot of time on it. I’m still, and luckily, an expert in my field. People reach out to me and ask me to review things all the time. I often say no because this job takes all of my efforts.

Q: How do you plan to mentor and cultivate the next generation of scholars at John Jay College?

Dr. Pease: Mentorship is a critical part of success in our field. I am a college professor because of mentorship, and I think some of my success is because of the mentors that I’ve had who’ve nurtured my talent. I want that for every faculty member at John Jay. So, we do have a junior faculty mentoring program, and that’s a great start, but it can’t be the end. One of the things that I’ve tried to foster is a collaborative culture of support, right? Mentoring isn’t always a vertical relationship of a senior and a junior faculty member. It is often about communities that collaborate and support one another. And so, you know, we do have writing boot camp days when faculty get together. They talk about their research at lunch, but they also just write together. Hopefully, departments are nurturing this sort of lateral mentorship as well. Our Office for the Advancement of Research is partnering senior scholars with more junior scholars to work on this. Another thing that I think is really helpful is that we’ve appointed a Distinguished Faculty Fellow for research at the college, Dr Preeti Chauhan. She’s been mentoring a lot of faculty on how to get grants. That’s an important step for a lot of faculty and sort of a milestone, and I’m hoping that that will help more faculty understand how to get grants and how to be a national player.

Q: What are your long-term aspirations for John Jay College under your leadership, and what criteria will you use to measure the success and impact of the initiatives you plan to implement?

Dr. Pease: I am mindful that being provost is a temporary position and that I am a sprinter in a relay race, right? I’ve taken this role from someone, and I will have to pass it on to someone; what I want, what I hope is to achieve, if not at the end of my Provostship, at least in the next two, is that one will increase our graduation rates at least by 20 percentage points so that we’re up in the 70s by the time I’m done. Second, I do want to tell John Jay’s research story. We already have brilliant, big-hearted professors who are doing, you know, field-defining research; somehow, that story has to be communicated in a way that people understand John Jay is where exciting research happens, and I want that to be a known fact.

I want to be the best feeder of our students getting into law school that we can be. We are known as a baccalaureate-origin school for Hispanic students pursuing doctorates. That’s fantastic. I want to be the best at that. Right? Our students come to us with their hopes and dreams, and they are worthy of their aspirations. I want to be able to serve them in a way that propels them into outstanding futures.

New Faculty Spotlight Interview: Prof. Alessandra Early

Professor Alessandra Early is an assistant professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College and a dedicated criminologist whose academic journey is rooted in a passion for understanding the intricacies of human behavior and identity. From a childhood curiosity that questioned the fundamental nature of numbers to becoming a professor, her commitment to knowledge has been unwavering. With a background in psychology and sociology, she transitioned to criminology, driven by a fascination with the dynamics explored in shows like Criminal Minds.

Dr. Early’s research delves into the intersection of spatial dynamics, identity formation, and behavior, particularly focusing on queer experiences and the impact of social spaces. In this Q&A, Dr. Early shares her insights into research, professional achievements, mentoring philosophy, and her vision for contributing to the academic community.

Can you share a bit about your academic journey and what led you to pursue a career in criminology?

Since I was young, I’ve wanted to help people and investigate the “hows” and “whys” behind everything around me. As a kid learning math, I peppered my mother with questions incessantly, completely unsatisfied with the superficial and desperately seeking to learn a greater meaning. “Why is a one a one?” I asked. “What makes a two a two?” That pursuit of knowledge has become a core mission in my life and led me to become a professor today.

As an undergrad, I majored in psychology and sociology. I fantasized about becoming an FBI profiler thanks to my obsession with Criminal Minds, and I kept finding myself drawn to criminology courses. That tendency persisted when I pursued my master’s in sociology as well; I really connected with some professors who really believed in me and my work. I decided to follow that path and complete my PhD in criminology and criminal justice. (Though I moved away from law enforcement.)

Being a professor means I always have to adapt and evolve as new knowledge develops, which I love. I enjoy reading, learning, and problem-solving and my job asks me to engage in all three. Interacting with students is such a privilege because I want them to have the same light-bulb “Aha!” moments in my classrooms that I used to experience as a student myself.

Could you highlight some of your key research interests or projects, and how do you see them contributing to your field or broader society?

Broadly speaking, my research is rooted in three intersecting areas: Spatial and place-based dynamics, identity formation, and behavior. Specifically, I am interested in the ways in which spaces, particularly social spaces, impact how people understand themselves and can encourage or inhibit behavior. My dissertation, for example, explored how the historical, social, and cultural spatial dynamics of queer social spaces (such as bars and clubs), and using substances within them, can impact queer identities. One finding was that queer people strategically used substances to explore their identities and navigate queer vs. heterosexual social spaces.

Another project investigated the interplay between space(s), identities, and substance use through the experiences of primarily white heterosexual women who had experience with the rural methamphetamine market before being incarcerated. We emphasized the complex, violent, and empowering strategies that women used to confront and overcome gendered and sexualized expectations while participating within the patriarchal market.

My research interests engage in “queering” or destabilizing normative understandings of how we move through our environments, create meaning within them, formulate our identities in opposition to or with the help of those environments, and how those environments and the meanings we prescribe to them encourage or inhibit our behaviors.

Have there been any significant milestones or achievements in your professional journey that you are particularly proud of?

Currently, I’m most proud of my paper, The Role of Sex and Compulsory Heterosexuality Within the Rural Methamphetamine Market, which was published in Crime & Delinquency. Because of the precarious nature of grad school, sometimes it’s hard to see a project from inception to completion. To my and my co-author’s knowledge, this article represents the first paper to apply a queer criminological framework to examine the experiences of primarily cisgender and heterosexual white women. In 2022, the paper earned first place in the inaugural student paper award from the Division of Queer Criminology at the American Society of Criminology.

Do you have a mentoring philosophy, and how do you envision supporting students in their academic and professional development?

I approach teaching as a way to co-construct knowledge with students, with the goal of transforming the classroom into an encouraging space and making the material relatable and accessible. My mentoring philosophy builds upon that same foundation, emphasizing a collaborative and comfortable environment that I strive to offer all my mentees. I often describe my personal experiences with employing particular methodologies, concepts, or theories in order to demystify learning and the process of conducting research. In one-on-one student conversations and larger panel events, I speak candidly and transparently about the joys and challenges of being a Black queer woman in academia. While at conferences, I carve out time to bond with my mentees and ensure that I introduce them to fellow academics who share their interests to encourage networking and professional advancement. I let them know that my door is always open.

How do you envision contributing to the growth and development of our academic community in the coming years?

Although I have only spent a few months here at John Jay, I’m currently working to develop new courses that consider the ways in which queerness intersects with the carceral system and deepen our understanding of qualitative methodologies. I also look forward to carving out pathways that combine critical analyses and intersectional education.

Outside of academia, what are some of your hobbies or interests?

Outside of academia, you can find me practicing Matsubayashi Shorin-Ryu karate and Matayoshi Kobudo (traditional weapons). Currently, I am a Shodan (1st-degree black belt) and I am preparing for my Nidan (2nd-degree black belt) test in the fall of 2024! I’ve also recently rekindled my love for video games (after a long hiatus during graduate school) and I’m back to gaming with my friends!

If you could give one piece of advice to students aspiring to excel in your field, what would it be?

Throughout my educational career, I have always carried my grandmother’s mantra and work ethic, which is the best advice I’ve ever received: Good, better, best. Never let it rest until the good is better and the better is the best. Though I’d make one small amendment — rest is important! Be sure to take breaks, but keep those intellectual fires burning.

Q&A With Dr. Suvi Rautio, 2023 John Jay Research Visiting Fellow

In our Q&A series, the Office for the Advancement of Research (OAR) is excited to spotlight the 2023 Visiting Research Fellow, Dr. Suvi Rautio for the vital research she has conducted. Suvi is an anthropologist specializing in urbanization and transnationalism in rural China. Guided by family history stories, she delivered a public lecture to the John Jay College Community on April 4, 2023, titled: The Love Letters: Dreams at the Dawn of the Mao Zedong Era.

In this Q&A, Suvi shares her experience as a Visiting Fellow at John Jay College, discusses the research projects she’s worked on, and offers academic advice.

Tell us about your career path?

I started my career path in Beijing, China, working on a large range of different jobs, most of which were completely disconnected from academia and anthropology. Having grown up in Beijing, I had always been concerned in the impact that China’s breakneck development was having on the environment. I grew increasingly curious in the experience of environmental loss – in particular, how this loss alters people’s sense of belonging. This curiosity led me to work for Greenpeace where I led a research team to understand what forms of messaging and campaign strategies resonates with the broader Chinese audience. This felt exciting and meaningful, but it also did not feel like I was doing enough. I was seeking answers to bigger questions. Eventually I understood that I needed to return to academia to attend to my curiosity.

When I started a PhD in anthropology, my research in Southwest China steered me away from questions on the environment to cultural heritage. Although I was no longer focusing on environmental change, my interests in place-making and belonging have remained central to my research. To this day, my anthropological analysis pursues to find answers to how people’s connections to place and belonging change when they experience a sense of loss in one form or another.

What shaped you on your journey to follow your family’s history?

I always knew I wanted to do research on my family history. Growing up in Beijing, I wanted to understand what my family members experienced during the Maoist era — a time in which China was a very different country from the one I was familiar with. My family members did not share or openly speak about stories of the past spoken. Something inside of me has always wanted to understand and peel the layers of my family’s silences.

Maybe a part of this drive was to understand my father’s story growing up in Beijing, which I thought might help me make sense of some of the feelings that I was experiencing living in Beijing. I have always been a bit torn by the experience of feeling a deep association towards a city that I spent most of my childhood and early adulthood but where I am at the same time treated and seen as a foreigner and thus an outcast of the wider Chinese public society. Maybe if I can understand how these processes have been experienced through the lives of my family members, I can also find explanations for my own.

At the beginning, I was unaware that studying my family history was something that I could do as an anthropologist. I thought a study on my own history would appear too self-centered, and of little interest to outsiders. It was only when I was exposed to Alisse Waterston’s work (through Paul Stoller) did I learn that this is not the case. Alisse’s work has been and continues to be fundamental in shaping my journey conducting an intimate ethnography on my family.

My previous research was also fundamental in paving the path to studying my family history. Before my PhD research, I would not have been ready to pursue research on my family history. Academia is structured around critical thinking and critique, and I was scared of having to face that critique on something that is so personal. I was not ready to attend to that. Little did I know that my PhD would also become very personal, and in my dissertation I was very honest about the intimate relationships I formed with my interlocutors. This intimacy has been faced with critique. Rather than silencing those intimacies, writing about them has helped me gain a level of professionalism and courage as a writer and anthropologist. Most importantly, as an anthropologist, I have grown to understand that my research projects tends to get very personal very fast. I now understand that rather than fearing that feeling of intimacy, it is something I need to come to terms with.

Why did you want to share your story with the John Jay Community?

It was such an honour to be invited to share my work at a college-wide lecture with the John Jay Community. I wanted to take the opportunity to share my story and to challenge myself by presenting some initial material I have been collecting on my project. Sharing my story in front of my students and peers felt meaningful and I am very appreciative of the opportunity that was offered to me.

Based on the love letters you shared with us, what does love mean to you?

Love is about offering our thoughtful attention and care to someone or something. The stories that unfold in the love letters has taught me that. I think this quote, which I mention in my talk written by Armi, my grandmother, in her letter to my grandfather epitomizes how unrestrained love should be:

“Love is about whether we can understand and appreciate each other, and whether we are able to speak the same language of heart. And if we don’t understand each other in the beginning, we must be able to show that we can give the other an opportunity for mental liberty and give up our own ideas if we feel we are wronged.”

How does the love letter lecture at John Jay differ from other events you discussed?

I often present my work at conference panels and am more familiar with presenting my work within the time constraints of 10 to 20 minutes. Presenting at John Jay offered a rare opportunity to share my work beyond these time constraints. I also really appreciated having time for questions from the audience. For me, it’s these moments hearing about how my research engages with others that makes academic events, such as the one that John Jay offered me, so meaningful and worthwhile.

Overall I was really impressed by how well organized the lecture at John Jay was – from the preparation of the food and drinks, to the marketing and promotion, and all the other backend work that Remmy Bahati worked hard to put together. I was also impressed that the college had organized a professional video producer to film the lecture. Justin Thomas, the producer did a great job at this.

How did the speech make you feel?

I was so nervous about my presentation before the event. When it was over, a wave of relief swept over me when the audience showed so much enthusiasm and support towards my project. It was also moving to hear how my presentation resonated with audience members. This gave me a big boost of energy to continue moving forward with my project. Overall, the event gave me confidence to continue to seek opportunities to discuss and share my work.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Thank you John Jay for this opportunity to share my work!

Frank Pezzella Wants Increased Accountability on Hate Crime Reporting

During the chaotic years of the Trump Administration, the United States experienced a rise in hate crimes. This increase has been confirmed by FBI data collection, media reporting, and independent scholarship. According to Dr. Frank Pezzella, an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College and a scholar of hate crimes, four out of the past five years, from 2015 to 2019, have seen consecutive increases in hate crime offending in this country, something he says is new. Nine of the ten largest American cities had the most dramatic increases in hate crimes – including New York City.

Hate crimes, or bias crimes, are strictly defined by the FBI. The organization sets out 14 indicators that must be present for a criminal offense to be classified as a hate or bias crime, that provide objective evidence that the crime was motivated by bias. But according to Dr. Pezzella, the evidence to meet those criteria isn’t always clear. Not every hate crime is as flagrant as the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016 or the 2018 attack on Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue. To establish a hate crime was committed, first responding police officers must look for evidence of bias motivation – what Pezzella calls an “elevated mens rea” requirement. But bias can only be committed against legally protected categories, like race and ethnicity, sexual or gender orientation, disability, or religion, which vary from state to state. And the additional paperwork and procedural requirements that come with classifying an incident as a hate crime are, in his words, disincentivizing police reporting.

Undercounting Hate Crimes

The result of these complications is rampant underreporting. In his new book, The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America, Dr. Pezzella looks at the reasons why hate crimes are so undercounted in the United States, and proposes some solutions for what law enforcement and policymakers can do to correct the issue. Since the enactment of the federal Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990, which required the Attorney General to collect data about hate crimes, the FBI has been fulfilling this mandate in the form of the Hate Crime Statistics Program, published annually as part of the Uniform Crime Report. According to Dr. Pezzella, since 1990 the UCR has reported an average of roughly 8,000 hate crimes per year; but victims, he says, report around 250,000 hate crimes per year. He attributes this substantial gap to a variety of factors including the evidentiary and procedural barriers noted above. In addition, only about 100,000 of these victimizations are ever reported to the police in the first place. And when victims do report, police departments are under no legal requirement to pass their findings on to the FBI.

The result of these complications is rampant underreporting. In his new book, The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America, Dr. Pezzella looks at the reasons why hate crimes are so undercounted in the United States, and proposes some solutions for what law enforcement and policymakers can do to correct the issue. Since the enactment of the federal Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990, which required the Attorney General to collect data about hate crimes, the FBI has been fulfilling this mandate in the form of the Hate Crime Statistics Program, published annually as part of the Uniform Crime Report. According to Dr. Pezzella, since 1990 the UCR has reported an average of roughly 8,000 hate crimes per year; but victims, he says, report around 250,000 hate crimes per year. He attributes this substantial gap to a variety of factors including the evidentiary and procedural barriers noted above. In addition, only about 100,000 of these victimizations are ever reported to the police in the first place. And when victims do report, police departments are under no legal requirement to pass their findings on to the FBI.

“Of the roughly 18,500 police departments, only maybe 75% participate in the Uniform Crime Report hate crime reporting program – note that it is voluntary,” says Pezzella. “So we don’t even know about hate crimes in 25% of precincts. And of the participating 75%, roughly 90% report zero hate crimes every year. So one of the reasons we wrote the book is that, either we don’t have hate crimes the way we think we do, or we have a systemic reporting problem.” It’s obvious which he believes is true.

The consequences of underreporting hate crimes are severe, Dr. Pezzella says. “To the extent that we underreport both the type and extent of victimization, it really does put a specific policy issue in front of us. We need to know who’s being affected, how they’re being affected, and the extent of the effect, in order to fashion remedies.” The only way to target treatment and services for the most vulnerable and likely victims is through accurate reporting.

Remedying Undercounting

In order to remedy undercounting and better target policy, Dr. Pezzella presents a number of recommendations in The Measurement of Hate Crimes in America. He calls for changes to take place within police departments, at the level of state and local politics, and in the criminal legal system. First, he suggests that every precinct have a written and clearly posted hate crime policy, and that every officer be trained to understand the rules for identifying bias crimes and the statutes governing them in their particular state. He would also like to see greater police-community engagement on this issue, with better tracking of non-criminal bias incidents – like seeing a swastika or other racist tag in the neighborhood – which Pezzella says often lead to violent bias crimes. He would especially like to see hate crime reporting made mandatory, with penalties or audits following a departmental report of zero bias crimes in a year.

Stepping out of police departments, Dr. Pezzella also calls for greater engagement from state and local politicians, who after all control the purse strings as well as set state legislation, but who are often hesitant to call attention to a problem with hate crimes in their district. Finally, he wants prosecutors’ offices to commit to seeking hate crime convictions, rather than settling for the easier task of convicting an offender for non-bias equivalents. With every actor across the board invested in tackling hate crimes and being transparent and proactive about applying best practices, offenders are put on notice that the community, including police, won’t allow these harmful crimes to continue.

Vicarious Victimization

Dr. Pezzella has been studying hate crimes since his graduate school years at SUNY-Albany, but he doesn’t feel he’s reached the end of this line of research. Going forward, he is interested in studying the deleterious and vicarious effects hate crimes can have on the victims’ communities. Because bias-motivated offenders target victims based on what they are rather than what they do, Dr. Pezzella says, there is a sense that anyone could become the next victim. This impersonal threat undermines societal ideals of trust and equality, and can even affect property values, as whole groups feel unsafe in certain areas and may be forced to relocate. Pezzella also mentions the psychological and emotional impacts of feeling under threat for simply being who and what you are. “When a victim goes home and says they were a victim of a hate crime, in what way does it impact the quality of life or sense of safety for secondary victims [i.e., the victim’s community]?” he asks. “What do they do? While we understand the direct impact, we know less about this vicarious impact, and how far it extends beyond the primary victim.”

He also has his eye on current events, especially the rise of domestic terrorism in the United States. Dr. Pezzella is concerned about the growing number of organized hate groups in recent years, and how emboldened they have been by rhetoric from the top levels of government. While many mass shootings have been categorized as domestic terrorism, Pezzella also sees evidence of bias that might categorize these events as hate crimes. If they are being left out of crucial counts that help to allocate resources and fight back against hate in this country, he wants to know.

Dr. Frank Pezzella is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College. His primary research focus is on the causes, correlates, and consequences of hate crimes victimizations. He also conducts research on issues that relate to race, crime and justice. In addition to his most recent book, he is also the author of Hate Crime Statutes: A Public Policy and Law Enforcement Dilemma, as well as numerous peer-reviewed articles.

Dr. Frank Pezzella is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at John Jay College. His primary research focus is on the causes, correlates, and consequences of hate crimes victimizations. He also conducts research on issues that relate to race, crime and justice. In addition to his most recent book, he is also the author of Hate Crime Statutes: A Public Policy and Law Enforcement Dilemma, as well as numerous peer-reviewed articles.

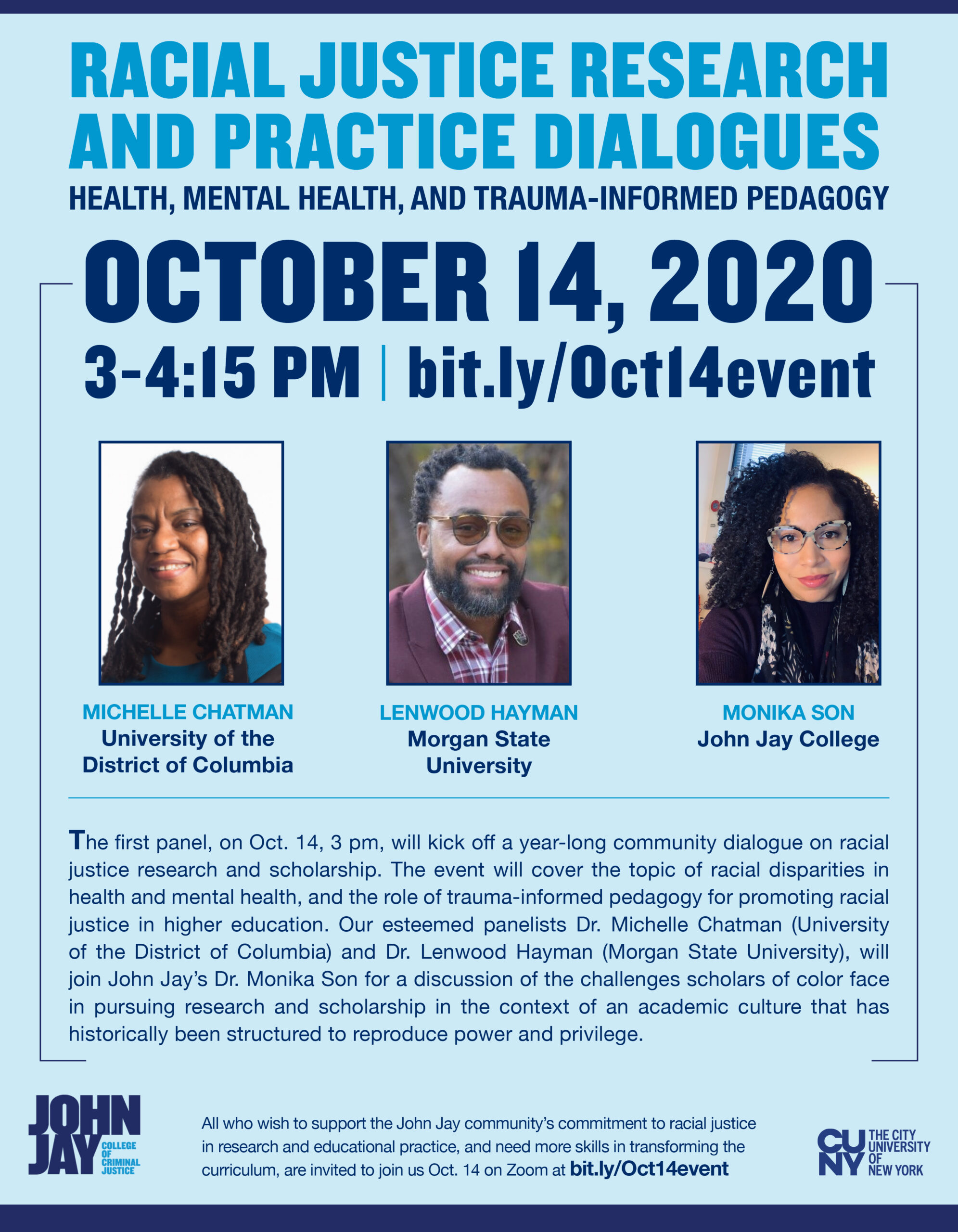

Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues 2020-23

The Office for Academic Affairs through its Office for the Advancement of Research, in collaboration with Undergraduate Studies and a faculty leadership committee representing Africana Studies (Jessica Gordon-Nembhard), Latinx Studies (José Luis Morín), and SEEK (Monika Son), sponsored a year-long community dialogue on racial justice research and scholarship across the disciplines. John Jay College faculty, students, and the broader community were invited to join four panel discussions and four hands-on workshops that invited a more in-depth discussion about changing the ways we teach and learn – specifically, by facilitating meaningful engagement with scholarship by and about people of color, and promoting the incorporation of research on structural inequities into curriculum college-wide. Over the course of the 2020-2021 academic year, events covered multi-dimensional topics including:

- racial disparities in health and mental health and trauma-informed pedagogy;

- the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative;

- economic inequality; and

- racism and discrimination in the criminal legal system.

Each panel was facilitated by a John Jay faculty member who also led a follow-up workshop intended to engage participants more deeply in the subject matter and promote best practices for cultivating racial justice in our classrooms and around the college. Each panel was recorded, and the recordings can be found below, as well as resource guides for further self-guided learning and curricular reform.

Series events, recordings and resources

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Event #1: Health, Mental Health, and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy

Panelists: Dr. Michelle Chatman (UDC) & Dr. Lenwood Hayman (Morgan State University)

Facilitator: Dr. Monika Son (JJC)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/NYTxARHOALw

Resources:

- Ayers, W., Ladson-Billings, G., & Michie, G. (2008). City kids, city schools: More reports from the front row. The New Press. Introduction, pgs 3-7.

- Chatman, MC. (2019). Advancing Black Youth Justice and Healing through Contemplative Practices and African Spiritual Wisdom. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 6(1):27-46.

- Monzó, L. D., & SooHoo, S. (2014). Translating the academy: Learning the racialized languages of academia. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(3), 147–165. DOI: 10.1037/a0037400

- Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Arch of Self, LLC, https://www.yolandasealeyruiz.com/archaeology-of-self

For additional suggested readings, prompts for discussion, and curricular resources, download our full event guide: RJD Event 1.1 Homework and Readings.

Event #2: Race and Historical Narrative — Correcting the Erasure of People of Color

The second panel in the OAR/UGS Racial Justice Research and Practice Dialogues series, on November 11 at 3 pm, will shine a light on the erasure of people of color from the historical narrative commonly taught in the United States. This erasure is harmful to students of color in particular, as they do not see themselves represented in the stories told about this country, and actively harms people of all races by failing to present an accurate picture of the country’s founding and history.

Panelists: Dr. Paul Ortiz (UFL) & Dr. Suzanne Oboler (John Jay College)

Facilitator: Dr. Edward Paulino (John Jay College)

Event recording: https://youtu.be/WRIDHIA_a94

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the RJD Event 2.1 – Readings.

Event #3: Economic Inequality and Wealth Disparities

Panel Discussion – March 24, 2021, 4:30 – 5:45 pm

Panelists: Dr. Naomi Zewde (CUNY SPH) & Dr. Stephan Lefebvre (Bucknell University)

Facilitator: Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard (JJC)

Event Recording: https://youtu.be/_lp93i3EHqE

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Economic Inequalities – Resources.

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Event #4: Racism in the Criminal Legal System

Panel Discussion – April 21, 2021, 3 – 4:15 pm

Panelists: Dr. Jasmine Syedullah (Vassar College) & Professor César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández (University of Denver, Sturm College of Law)

Facilitator: Professor José Luis Morín (JJC)

Recording: https://youtu.be/OZ8N-c7Gob0

Resources: For suggested readings that may be helpful in placing the panel discussion in context, download the Racial Justice Dialogues – Resources – Racism in the Criminal Legal System

The series continued in academic year 2021-2022, expanding the scope of the discussions with panels on racial equity in disaster recovery.

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

Event #5: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: CBOs, NGOs, and Government Collaboration

The fifth panel took place on November 1, 2021, and addressed the interdependent roles of government agencies, community-based and non-governmental organizations in promoting or hindering equitable outcomes in post-disaster situations. Panelists included Kim Burgo (Catholic Charities), Craig Fugate (One Concern), Dr. Jason Rivera (Buffalo State College), Dr. Warren Eller (John Jay College), and Dr. Dara Byrne (John Jay College). Find the recording at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQkjxw6RcKg.

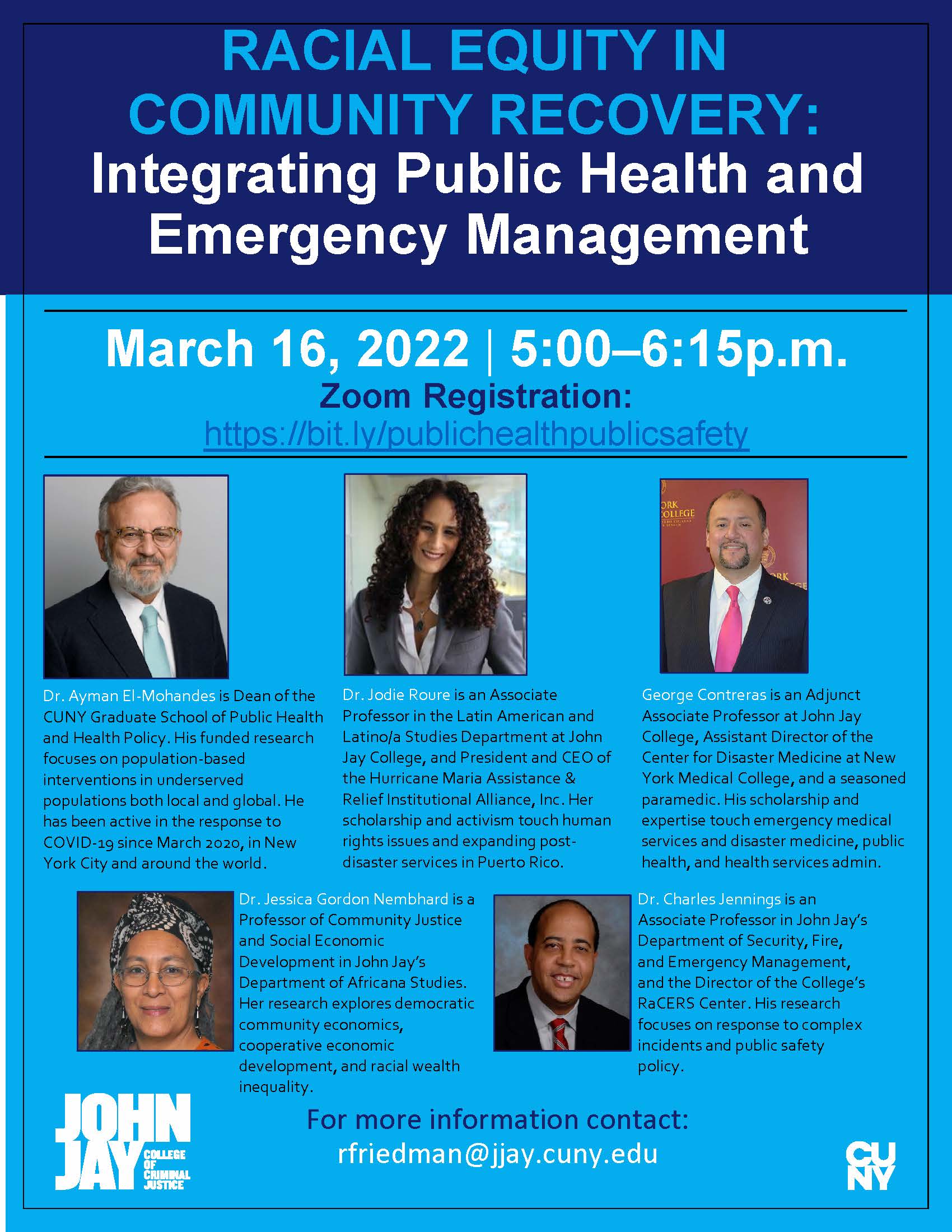

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

Event #6: Racial Equity in Community Recovery: Integrating Public Health and Emergency Management

The sixth panel in the series, which took place on March 16, 2022, continued the theme of racial equity in disaster recovery. Panelists explored the overlapping roles of the institutions of public health and public safety in promoting equitable outcomes in post-disaster recovery, addressing the intersectional challenges faced by people of color and other marginalized communities. The conversation took special note of the particular context of post-COVID recovery. The participants were Dr. Ayman El-Mohandes (CUNY Graduate School of Public Health), Dr. Jodie Roure (John Jay College), and George Contreras (New York Medical College, John Jay College). The moderators were Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard and Dr. Charles Jennings (John Jay College). A full recording of the event is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4u9wUyjr5Sg&list=PL-B85PTQbdJj5UJhqiddjs1_9p90pZXTZ&index=6.

Resources:

- , 2020: COVID-19: A Barometer for Social Justice in New York City, American Journal of Public Health

- El-Mohandes, A., White, T.M., Wyka, K. et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adults in four major US metropolitan areas and nationwide. Sci Rep

- Roure, Jodie G. The Reemergence of Barriers During Crises and Natural Disasters: Gender-Based Violence Spikes Among Women and LGBTQ+ Persons During Confinement. Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, pp 23-50, 2020.

- Jodie G. Roure, 2020 presentation: Children of Puerto Rico & COVID-19: At the Crossroads of Poverty & Disaster.

- Jodie G. Roure, Immigrant Women, Domestic Violence, and Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico: Compounding the Violence for the Most Vulnerable. The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law, 2019.

- Contreras GW, Burcescu B, Dang T, et al. Drawing parallels among past public health crises and COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.202.

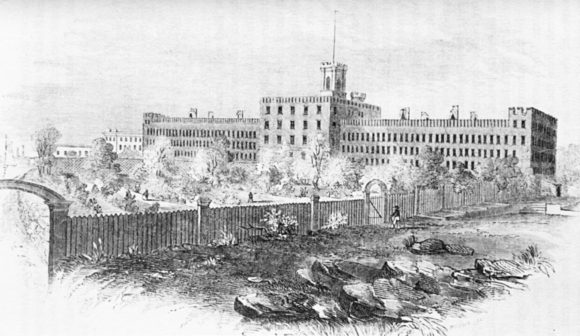

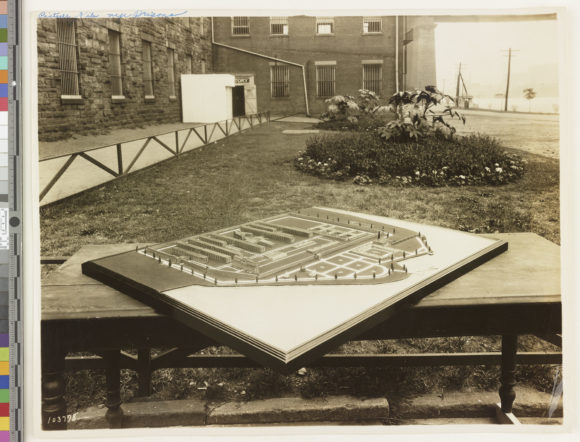

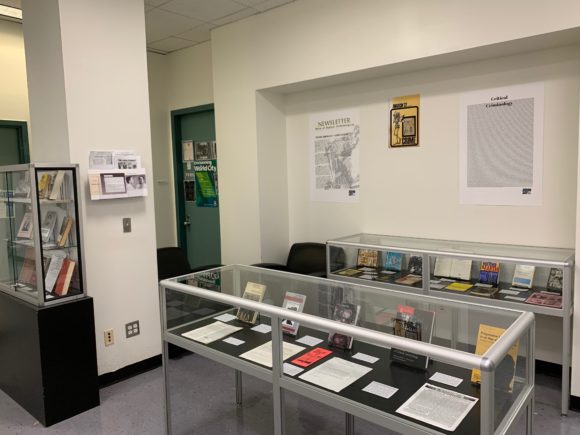

A Critical History of Incarceration in New York City

Dr. Jayne Mooney is an Associate Professor of Sociology at John Jay and a member of the doctoral faculty of Women’s Studies and Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is also a director and founding member of the Critical Social History Project (CSHP), a research initiative and part of John Jay’s Social Change and Transgressive Studies Project that draws on archival material to shed light on the history of incarceration in New York City.

The project began in 2015 with a conversation spurred by reporting on abuse, poor conditions, and a rash of tragedies at Rikers Island; how best, Mooney and colleagues wondered, to preserve the memories of those who had been affected by the infamous jail, including not only the incarcerated but also their friends and families, guards and educators? And so they began the “Other City” project, which forms the largest component of the CSHP. Informed by their research into the history of New York’s penitentiary system, Mooney’s working group is pointing out the problems inherent in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration’s proposal to close Rikers and open four new city jails.

“On the most basic level, what we’re showing is that the current proposals are reinventing the wheel. It’s the same thing that’s always happened. Closing an institution and setting it up again, you’re going to have the same problems, because you’re not getting to those deep-rooted, structural issues,” says Mooney.

Reinventing the Wheel

In a forthcoming article, “Rikers Island: The Failure of a ‘Model’ Penitentiary” due to be published in The Prison Journal in 2020, Mooney and her co-author, CUNY graduate student Jarrod Shanahan, go through the instructive failures of incarceration reform in New York City back to the 1735 construction of the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction. They argue that a lack of historical documentation has allowed policymakers to strategically “forget” the failures of past “model” or “state of the art” institutions, continually replacing old jails with new without a look at the larger issues that have led to waves of highly praised but ultimately unsuccessful penal reform.

Set against the backdrop of historical, social and political context, Rikers’ closure and the proposals to replace it look familiar. “All of these places opened in the spirit of optimism—everything was going to change. And then everything goes wrong, these institutions are denounced as embarrassments, and the decision is made to close them down and rebuild. Of course, that’s what’s been happening in the present moment,” Mooney says. She and her colleagues encourage the Mayor’s Office to look beyond the walls of the prison for new solutions to social problems faced by New York and, indeed, the United States.

(Read her December 2019 letter to The Guardian on the subject, “Rikers has failed like others before it, but the solution is not new jails.”)

Preserving Voices, Preserving Justice

Mooney’s challenge to the new proposals is grounded not only in her work in political social history, but also in her background as a critical criminologist. “There’s a very strong abolitionist line all the way through critical criminology,” she notes, which informs the way the Critical Social History Project has approached critiques of the plan to build new jails.

The CSHP isn’t only focused on documenting mass incarceration in NYC. As the Vice Chair of the American Society of Criminology’s Critical Criminology and Social Justice Division, as well as the archivist, Mooney has been accumulating archival information related to the division and the field’s history of activism. The CSHP’s Preserving Justice component, jointly directed by Mooney and Visiting Scholar Albert de la Tierra, has created an exhibition in the Sociology Department displaying some of the core critical criminology texts. It’s open to any students, faculty or staff who are interested in the history of the field and the work of its important thinkers.

Expanding Research Horizons

Mooney is proud to talk about her team of dedicated researchers, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students. With the help of their diverse experiences and interests, the Critical Social History Project is expanding its remit, from the history of Rikers Island to topics including the history of women’s incarceration, other New York carceral institutions including the Tombs and Sing-Sing, mental illness and incarceration, and more. Together, they are showing the persistence of the problems related to the history of mass incarceration, no matter where in history you begin your research—up to and including the present day.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

The Critical Social History Project is directed by Jayne Mooney and Albert de la Tierra. Other members are Sara Salman (Victoria University of Wellington), Nick Rodrigo, Jacqui Young, Susan Opotow and Louis Kontos, as well as John Jay students Camilla Broderick, Anna Giannicchi, Tayabi Bibi, Andressa Almeida, Marcela Jorge-Ventura, and Audrey Victor.

You can learn more by visiting the Critical and Social History Project’s website.

Using Crime Science to Fight for Wildlife

There is no question that the fashion industry causes great harm to the environment. The industry’s faddish nature, combined with the overproduction of low-cost, low-quality pieces, is designed to encourage overconsumption. Production of fast fashion garments eats up precious resources, like clean water and old-growth forests, and discarded clothing can sit in landfills for hundreds of years, thanks to synthetic materials used in construction.

According to scholars Monique Sosnowski—a Ph.D. candidate in criminal justice at the CUNY Graduate Center—and John Jay Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice Dr. Gohar Petrossian, pollution is not the fashion industry’s only crime. In a new article, they investigated what species were being utilized for the fashion industry, which is worth over $100 billion globally, in order to better understand the damage the industry causes to wildlife and wild places.

Sosnowski and Petrossian looked at items imported by the luxury fashion industry and seized at U.S. borders by regulatory agencies between 2003 and 2013. Their study found that, during that decade, more than 5,600 items incorporating elements illegally derived from protected animal species were seized. The most common wildlife product was reptile skin—from monitor lizards, pythons, and alligators, for the most part—and 58% of confiscated items came from wild-caught species. The authors also found that around 75% of seizures were of products coming from just six countries: Italy, France, Switzerland, Singapore, China and Hong Kong. The heavy involvement of the European countries was unexpected, according to Dr. Petrossian, because they are key players in fashion design and production but “don’t generally come up in broader discussions on wildlife trafficking.”

THE SCIENCE OF WILDLIFE CRIME

The paper applied “crime science, a body of criminological theories that focus on the crime event rather than ‘criminal dispositions,’ to understand and explain crime. The overarching assumption is that crime is an opportunity, and it is highly concentrated in time, as well as across place, among offenders, and victims,” says Dr. Petrossian. Their scientific approach enabled the authors to analyze patterns and concentrations in wildlife crime, which Sosnowski notes is among the four most profitable illegal trades.

“We are currently living in an era that has been coined the ‘sixth mass extinction,’” she says. “It is crucial that we understand the impact that humans are having on wildlife, from habitat loss to the removal of species from global environments. Fashion is one of the major industries consuming wildlife products.”

A background in wildlife conservation, including unique experiences like responding to poaching incidents in Botswana and rehabilitating trafficked cheetahs in Namibia, led Monique Sosnowski to a Ph.D. in criminology; she wanted to move beyond a more traditional conservation-informed approach to address what she’d seen in the field. Working with Dr. Petrossian on a series of studies applying crime science to wildlife crimes has given her a broader view of the effects of wildlife-related crime on global ecosystems.

CREATING SOLUTIONS, SAVING WILDLIFE

Why is it important to understand what species are most commonly used in luxury fashion products, and where they are coming from? A study like this one provides information about trends that policymakers can use to strengthen or focus enforcement and inform better understanding of the issues. Sosnowski calls this “the key to devising more effective prevention policies.”

Currently, global regulation of the trade in wildlife products, including leather, fur, and reptile skin that come from species both protected and not, is the province of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES); this treaty aims to ensure that international trade in wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. But the treaty is limited in scope.

“Given the prevalence of exotic leather and fur in fashion, we believe CITES and other regulatory bodies should enact policies on its use and sustainability in order to protect wild populations, the welfare of farmed and bred populations, and the sustainability of the fashion industry,” Sosnowski says.

Consumers also have a role to play. “We are all led to believe that products found on the shelves are legal, but as this study has demonstrated, that isn’t always the case. Consumers of these products are the ones who have the power to change the behaviors of a $100 billion industry. We need to ask questions about where our products were sourced, and respond accordingly.”

###

Summarized from EcoHealth, Luxury Fashion Wildlife Contraband in the USA, by Monique C. Sosnowski (John Jay College, City University of New York) and Gohar A. Petrossian (John Jay College, City University of New York). Copyright 2020 EcoHealth Alliance.

Podcasting at John Jay: Making Research Accessible

If you’re like us, you love podcasts enough that you’ve subscribed to more than you can listen to in a week of subway commutes. Podcasting, then called online radio, rose in popularity with the proliferation of mp3 players in the early 2000s. In tandem with other personal platforms like blogs, podcasts exemplified the “democratizing spirit” of the internet.

Today, they are big business. Since the release of Serial in 2014, podcasts have boomed. Monthly listeners have nearly doubled since 2014, from around 39 million Americans to an estimated 90 million. As the listening audience grows, quality improves, and bigger names get interested in the medium, advertisers are investing millions.

At John Jay, interest in podcasting has risen along with the medium’s growing potential. The college is home to a variety of podcasts, run by students, faculty and staff, on a rainbow of topics. For example, students in the English department work with Professor Christen Madrazo to write, produce, and edit Life Out Loud, which highlights the diverse voices and real stories of John Jay’s student body. We also have faculty working on podcasts hosted outside John Jay, podcasts run by research centers, and faculty and staff who produce their own shows, right here on campus.

We will introduce you to two homegrown John Jay podcasts that seek to translate scholarship into a form that everyone can understand. Meet Kathleen Collins, a Reference Librarian and Professor at John Jay College, and Nick Rodrigo, a CUNY Ph.D. candidate and John Jay College adjunct professor. While Kathleen is on her 38th episode of podcast Indoor Voices, and Nick has just released the first six episodes of They Are Just Deportees, both share the desire to take CUNY research out of the ivory tower and bring it to the community.

Kathleen Collins has been producing Indoor Voices since the summer of 2017. She started the podcast as “a way to highlight the fascinating things going on around CUNY that might not be widely known. There are so many inhabitants in the CUNYverse doing incredibly interesting things… We like being able to provide a low-stakes, easy-to-share platform for people to talk about their work.”

Kathleen Collins has been producing Indoor Voices since the summer of 2017. She started the podcast as “a way to highlight the fascinating things going on around CUNY that might not be widely known. There are so many inhabitants in the CUNYverse doing incredibly interesting things… We like being able to provide a low-stakes, easy-to-share platform for people to talk about their work.”

To Kathleen, the conversations are the key element. She and her co-host, La Guardia Community College librarian Steven Ovadia, interview CUNY faculty, students, alumni and staff members about their research or creative output; they have a great deal of leeway to highlight what interests them.

Nick Rodrigo is new to podcasting, overcoming challenges as he meets them in the course of creating They Are Just Deportees. The newly-launched show examines the various ways in which the U.S. immigration enforcement system shapes and controls the lives of migrant communities in this country. With co-host Darializa Avila Chevalier, TAJD helps listeners to understand “the multiple sites of border enforcement in the U.S., and the punitive effects of the country’s periodic moral panics on the ‘criminal alien.'”

Nick Rodrigo is new to podcasting, overcoming challenges as he meets them in the course of creating They Are Just Deportees. The newly-launched show examines the various ways in which the U.S. immigration enforcement system shapes and controls the lives of migrant communities in this country. With co-host Darializa Avila Chevalier, TAJD helps listeners to understand “the multiple sites of border enforcement in the U.S., and the punitive effects of the country’s periodic moral panics on the ‘criminal alien.'”

Nick, and his associates in the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime Working Group (the sponsor of the podcast), think this is a particularly relevant topic. “Immigrant rights have come under increasing threat from the state, with bans on immigration from Muslim majority countries, the detention of children at the U.S./Mexico border, and the pledge of this administration to increase the forced removal of all undocumented people. … It is vitally important that the deportation system — which expels up to 300,000 persons a year — be placed in the historical context of this country’s treatment of the ‘other,’ while focusing on the real time implications of the current system on immigrant communities.”

For both showrunners, podcasting is a great way to make sometimes-complex issues and scholarship more accessible to an average listener. Says Nick, “two of the major issues in scholarship today are the ‘ivory tower’ mentality of academics and a lack of interdisciplinary focus on major social issues. Conferences and public lectures can be delivered in such inaccessible language that they can be alienating to non-academics. Podcasting allows for the complex issues concerning immigration enforcement to be distilled and presented to the public in a way that is accessible and digestible, with the opportunity for the listener to pause, reflect, and reengage at their own pace. Podcasting also provides a platform for criminologists, sociologists, public health experts, geographers, and journalists to come together on an issue and, if the interview structure is good, a compelling narrative for change can be constructed.”

Kathleen also wants to make it easier for non-experts to engage with what CUNY produces. “There is so much going on within CUNY,” she says, “and it shouldn’t be hidden inside the academy. Podcasts are a good way to get people interested in new things — it’s a mini, portable seminar for your ears. But since Steve and I act as generalists in our role as interviewers, we can hopefully elicit a layman’s interpretation of what scholars are thinking and writing about. The point is to bring attention to the author or artist, and ask about their research and writing process and teaching — these topics bring the conversation to a universal level.”

Creating content to fit the platform can sometimes be challenging. Nick was “forced to learn new skills on the job,” but found that his struggles with editing gradually turned into confidence! Kathleen cites the extensive support and inspiration from other podcasters and staff at the college as a source of her success and joy in creating Indoor Voices.

In the end, she says she loves every episode she produces — thanks to the satisfying conversations and intimate connections she can form with guests during a 40 minute interview, each new episode supplants the last as her new favorite.

Check out the latest episodes of Indoor Voices, They Are Just Deportees, and more John Jay podcasts:

- Indoor Voices: J Journal founders Adam Berlin and Jeffrey Heiman have been producing the literary magazine for twelve years. The high quality creative work they feature deals with contemporary justice issues, but not always in a way you might expect.

- They Are Just Deportees: You can find the first six episodes on the Social Anatomy of a Deportation Regime website, or by searching on Spotify.

- Reentry Radio: The latest episode of the podcast produced by John Jay’s Prisoner Reentry Institute deals with employment discrimination against justice-involved individuals, with special guest Melissa Ader of the Legal Aid Society’s Worker Justice Project.

- This World of Humans: Host Nathan Lents talks to Hunter College researcher Dr. Jill Bargonetti about using mouse models to study triple-negative breast cancer.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border.

Dr. Luis Barrios has been a faculty member at John Jay College for 28 years, and at CUNY for even longer. During that time, he has worked on projects that blend social action and scholarship, involving gangs and gang violence, deportation, human rights, clinical work focused on trauma and abuse, and contemporary perspectives of life on the Dominican-Haitian border. Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

Dr. Yuliya Zabyelina

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

If you’re speaking about climate change, organized crime is there as well. It’s a global issue, and it’s not a standalone topic—it needs to be looked at together with other problems, from the point of view of different disciplines, so we can cross-fertilize solutions. Everything is connected with everything.

Recent Comments